Harold Macmillan Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Harold Macmillan to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early Years and Personal Life

- Political Rise

- Premiership

- “Winds of Change” and Decolonisation

- Retirement and Death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Harold Macmillan!

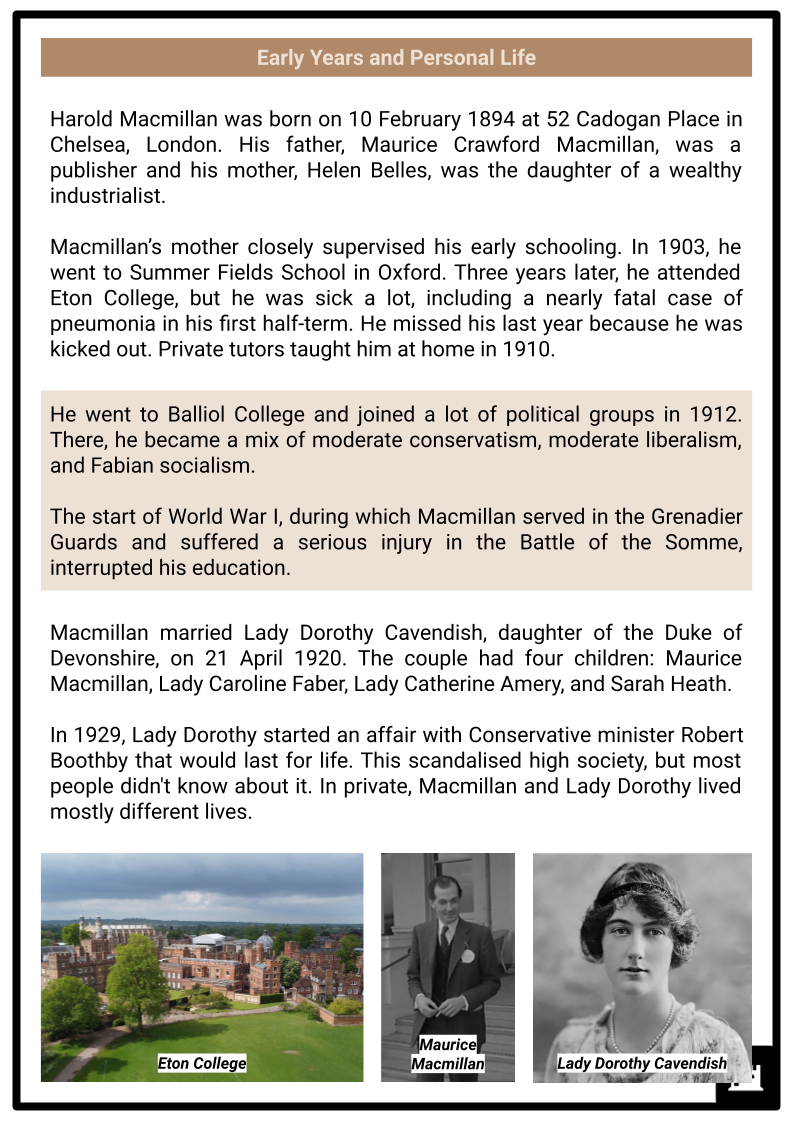

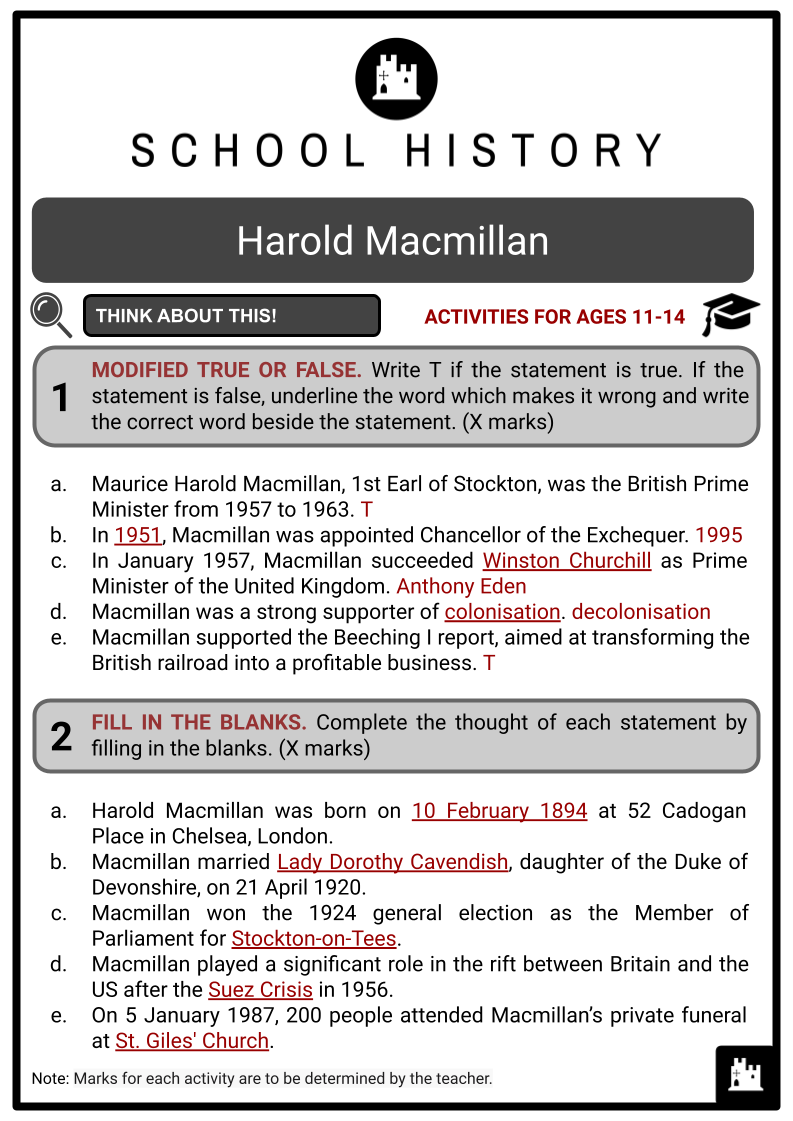

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, was the British Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963. A prominent figure in the decolonisation era, his policies and the "Winds of Change" speech advanced African nations towards independence. He resigned in 1963 under party pressure as a result of scandal, particularly the Profumo and Vassall affairs, which marred his premiership. His departure from office marked a transformative period in the journey of former colonies to sovereignty.

Early Years and Personal Life

- Harold Macmillan was born on 10 February 1894 at 52 Cadogan Place in Chelsea, London. His father, Maurice Crawford Macmillan, was a publisher and his mother, Helen Belles, was the daughter of a wealthy industrialist.

- Macmillan’s mother closely supervised his early schooling. In 1903, he went to Summer Fields School in Oxford. Three years later, he attended Eton College, but he was sick a lot, including a nearly fatal case of pneumonia in his first half-term. He missed his last year because he was kicked out. Private tutors taught him at home in 1910.

- He went to Balliol College and joined a lot of political groups in 1912. There, he became a mix of moderate conservatism, moderate liberalism, and Fabian socialism.

- The start of World War I, during which Macmillan served in the Grenadier Guards and suffered a serious injury in the Battle of the Somme, interrupted his education.

- Macmillan married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, daughter of the Duke of Devonshire, on 21 April 1920. The couple had four children: Maurice Macmillan, Lady Caroline Faber, Lady Catherine Amery, and Sarah Heath.

- In 1929, Lady Dorothy started an affair with Conservative minister Robert Boothby that would last for life. This scandalised high society, but most people didn't know about it. In private, Macmillan and Lady Dorothy lived mostly different lives.

Political Rise

1924: Elected as Member of Parliament for Stockton-on-Tees

- Macmillan won the 1924 general election as the Member of Parliament for Stockton-on-Tees. Stanley Baldwin's Conservative Party won this election by a wide margin and won a majority in the House of Commons. Macmillan's focus on local economic issues, his credible military service, and effective campaigning helped him secure support from the industrial electorate, fearful of socialism.

- As the Member of Parliament for Stockton-on-Tees, Macmillan's responsibilities included representing his constituents' interests in Parliament, participating in legislative debates and voting, addressing individual and community issues, and advocating for his party's policies alongside addressing local economic concerns.

1939: Appointed as a junior minister in Neville Chamberlain's government

- Macmillan was appointed as a junior minister in Neville Chamberlain's government at a pivotal moment in history, with the world on the brink of World War II due to growing tensions in Europe. As a junior minister, Macmillan supported senior ministers, represented the ministry in parliamentary sessions, and oversaw specific areas. He prepared legislation, responded to correspondence, and liaised with external stakeholders to ensure smooth government operations and policy implementation. His role as a junior minister gave him valuable experience in government and an inside view of the political landscape leading into the war.

1945: Became Minister Resident in North Africa, working alongside General Eisenhower during World War II

- As the Minister Resident in North Africa, Macmillan acted as the British government's senior representative in the region during World War II.

- He worked closely with military officials, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Forces in North Africa.

- His responsibilities included facilitating political and military cooperation, ensuring effective communication between the British government and military command structures, and helping to coordinate the administration of British policies in the region.

- His position required diplomatic skill and an understanding of both civilian and military needs during the complex operations of the war.

1951: Appointed as Minister of Housing and Local Government

- As the Minister of Housing and Local Government, Macmillan was tasked with addressing the severe housing shortage in Britain after the nation faced a significant challenge in rebuilding and creating new homes for those displaced by wartime bombing and slum clearances.

- He adopted the challenging objective set forth by the Conservative government to increase the rate of house building and sought to achieve the goal of building 300,000 new homes annually.

1955: Became Chancellor of the Exchequer

- In 1955, Macmillan was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, a key position in the British government responsible for economic and financial matters. As Chancellor, he was in charge of the Treasury, overseeing the nation's finances, economic policy, and budget.

- This role involves setting tax rates, managing government spending, and guiding the overall economic strategy of the country.

- Macmillan's time as Chancellor saw him dealing with the economic challenges of post-war Britain, balancing the need for economic growth with the constraints of managing the national debt and maintaining currency stability. His performance as Chancellor and his handling of the country's economic policy further solidified his standing within the Conservative Party.

1957: Succeeded Anthony Eden as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- In January 1957, Macmillan succeeded Anthony Eden as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom following Eden's resignation due to ill health and the fallout from the Suez Crisis. As Prime Minister, Macmillan led the country through a period marked by an improving economy, the easing of Cold War tensions, and the beginning of the decolonisation process, whereby numerous British colonies gained independence.

- He served as Prime Minister until October 1963, when he resigned due to health issues. His premiership was significant for guiding Britain through a transformative phase, both internally and in terms of its role on the world stage.

Premiership

- During Macmillan's first term as prime minister, from 1957 to 1959, he introduced numerous social reforms that gradually improved the standard of living for most people. Key legislation included the Clean Air Act in 1956, the Housing Act of 1957, the Offices Act of 1960, the Noise Abatement Act of 1960, and the Factories Act of 1961.

- Macmillan also initiated a graduated pension plan, a Child's Special Allowance for children whose parents have separated and left them without a parent, and reduced the average work week from 48 hours to 42 hours. He played a significant role in the rift between Britain and the US after the Suez Crisis in 1956. However, he was able to mend this division by cultivating a friendship with Eisenhower during the war and engaging in productive meetings in Bermuda.

- In 1959, he visited the Soviet Union and held discussions with Nikita Khrushchev. They reached an agreement to halt nuclear tests and arrange a summit involving leaders from both the Allies and the Soviet Union.

- Macmillan was a strong supporter of decolonisation. He helped the Gold Coast become independent as Ghana and the Federation of Malaya joined the Commonwealth of Nations. He also backed the British plan to make nuclear weapons, which worked in 1957. But because of this choice, the Windscale and Calder Hall nuclear plants had to handle more work, which caused the Windscale fire in October 1957.

- When the Soviet satellite Sputnik was launched, it caused a crisis of trust in the United States. Macmillan saw this as a chance to increase British power over the US. He wanted a more fair relationship between Britain and the United States, and he used the Sputnik incident to try to get Eisenhower to get rid of the 1946 McMahon Act.

- Aside from that, Macmillan set up "working groups'' between Anglo-Americans to look into issues of foreign policy and called for a "Declaration of Interdependence."

- Macmillan led the Conservatives to victory in the 1959 election, which gave their party a majority of 100 seats instead of 60. The campaign was built on the idea that the economy was getting better, unemployment was low, and people were living better.

- During Macmillan’s second government as prime minister from 1959 to 1963, there were problems in Britain’s balance of payments, which led Chancellor Selwyn Lloyd to freeze wages for seven months in 1961. This made the government less popular and led to a number of by-elections. Eight ministers were fired by Macmillan in 1962, including Selwyn Lloyd.

- Macmillan supported the Beeching I report, aimed at transforming the British railroad into a profitable business. The result was the implementation of the Beeching Axe, which resulted in significant reductions in permanent tracks and isolated towns from the train network. Macmillan initially planned for a four-power summit in Paris to discuss the Berlin issue. However, his perspective on the European Economic Community shifted following the unsuccessful Paris meeting, and his envisioned Anglo-American "working groups" did not materialise as he had hoped.

- After President John F. Kennedy was elected, the special relationship with the US continued due to his strong concerns for the Third World. Macmillan advocated for changes to capitalism to ensure employment for all and emphasised the importance of supporting developing nations.

- Early in the 1960s, Macmillan's handling of the Vassall and Profumo scandals raised questions about his competence. The Vassall scandal exposed a case of Soviet espionage within the Admiralty. John Vassall, a civil servant, had been blackmailed into passing sensitive information to the Soviet Union.

- The Profumo affair added another layer of controversy as it involved a scandalous relationship between the War Minister, John Profumo, and a model named Christine Keeler, who was also linked to Yevgeny Ivanov, a Soviet naval attache in London. The affair escalated into a national security crisis and raised concerns about the potential compromise of classified information.

- Macmillan faced criticism for his initial handling of these scandals, with some accusing him of being slow to take decisive action and effectively address the security risks and public concerns. By the summer of 1963, Lord Poole, the chairman of the Conservative Party, had pushed Macmillan to step down. Following a discussion with Butler, Macmillan agreed to step down in the event that Baron Hailsham was selected to succeed him.

- In a contentious move, Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home replaced Macmillan. On 18 October 1963, after seven years as prime minister, Macmillan submitted his resignation, believing that a backbench minority was pressuring him out of office.

“Winds of Change” and Decolonisation

- When Macmillan acknowledged the growing calls for independence and self-determination across the continent in his 1960 speech to the South African Parliament in Cape Town, he famously coined the phrase "Winds of Change." In this speech, he outlined the global shift towards decolonisation and emphasised its unstoppable momentum. His words served as a catalyst for decolonisation, echoing sentiments of liberation and self-governance. The speech underlined the need for recognition of burgeoning sovereignty and collaboration in international relations.

- Under his leadership, the sub-Saharan African independence movement gained momentum, mirroring the domestic and international pressures of the era. Fears of a potential union between white-ruled Southern Rhodesia and South Africa threatened the stability of the Central African Federation, which grouped Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland since 1953. When the costs of holding a territory outweighed the benefits, Macmillan realised it was wise to give it up.

- The British government's attempts to keep the Kikuyu people safe from Mau Mau insurgents during the Kenyan Emergency involved internment camps whose living conditions starkly reminded many of the concentration camps of Nazi Germany.

- These events, along with the pressing realities of costly wars, adverse global opinion, and the risk of Soviet influence in aiding "liberation" movements in the Third World, shifted Macmillan's perspective. He increasingly saw African colonies as liabilities rather than assets.

- By the time Macmillan left office, the Central African Federation had been dissolved by the end of 1963, and South Africa had departed from the Commonwealth in 1961 due to the policies he implemented, prevailing against the opposition of white minorities and groups like the Conservative Monday Club.

- The year 1963 also marked the creation of Malaysia through the independence of Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, and Singapore from British rule, a significant transition in Southeast Asia. President Sukarno of Indonesia vehemently opposed this new federation, asserting a claim over Malaysia.

- Tensions rose when Brunei, a British protectorate, faced an Indonesian-backed insurrection in 1962—a situation Macmillan addressed by dispatching Gurkhas to quell the uprising.

- Indonesia's subsequent campaign of konfrontasi ("confrontation") with Britain was another event Macmillan deeply resented. His apprehension about a full-scale confrontation with Indonesia stemmed from concerns about cost and further damage to British international standing.

- Macmillan’s tenure also saw critical developments in security and international relations. In 1961, he met with President John F. Kennedy to negotiate the Nassau Agreement, which involved the acquisition of Polaris missiles, reflecting ongoing efforts to sustain the ‘special relationship’ between Britain and the United States. The geopolitical landscape of the time was further complicated by the 1960 U-2 incident, which derailed attempts for a conciliatory summit in Paris.

- Macmillan's commitment to nuclear non-proliferation culminated in his significant participation in the negotiations leading to the signing of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty by the US, UK, and Soviet Union—a testament to his efforts in promoting global security and stability.

- The end of Macmillan’s administration marked not just a transition in British leadership but also a turning point in the decolonisation narrative as territories across Africa and Asia were set on the path to independence. His legacy in this transformative period included the initiation and support of policies that enabled nations to emerge from the shadow of the British Empire, setting the stage for a new era of international relations and nation-building.

Retirement and Death

- After resigning as Prime Minister in 1963, Macmillan was granted a hereditary peerage as Earl of Stockton, allowing him to continue serving in the House of Lords. Despite his retirement from active politics, he remained involved in public life and continued to be influential within the Conservative Party.

- However, his health began to decline in the 1980s, and he passed away on 29 December 1986, at Birch Grove, the Macmillan family mansion on the edge of Ashdown Forest, in Horsted Keynes, West Sussex. On 5 January 1987, 200 people attended his private funeral at St. Giles' Church. A public memorial ceremony was held on 10 February.

- His legacy as a statesman and his impact on the decolonisation process continues to be remembered and studied by historians and political analysts around the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Harold Macmillan?

Harold Macmillan served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. He was a key figure in post-World War II British politics and is known for his role in decolonisation and his efforts to rebuild the British economy.

- What were some of Macmillan's major achievements as Prime Minister?

Significant achievements of Harold Macmillan’s tenure include overseeing the decolonisation of Africa, famously encapsulated in his "Wind of Change" speech, initiating nuclear test ban treaty negotiations, and promoting the idea of a "mixed economy", which included both private enterprise and state intervention.

- What was the "Wind of Change" speech?

The "Wind of Change" speech was delivered by Harold Macmillan in 1960 during a tour of Africa. In the speech, he acknowledged the rising tide of national consciousness and the push for independence across the continent.