New Model Army Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the New Model Army to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Background

- Personnel and Weapons

- Contribution to the War and Influence

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the New Model Army!

The New Model Army, or New Modelled Army, was a standing army founded by Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War in 1645 and disbanded in 1660 following the Stuart Restoration. Unlike previous armies used in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms from 1639 to 1653, its personnel were not restricted to a single region or garrison but could serve wherever in the nation. To develop a professional officer corps, the army's leaders were barred from sitting in either the House of Lords or the House of Commons. This was done to encourage them to separate from the political and religious groups among Parliamentarians.

BACKGROUND

- Charles I of England saw himself as an absolute monarch with unlimited authority and a divine right to reign, but his refusal to compromise with Parliament, notably over money, resulted in a civil war from 1642 to 1651. The war fought between the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and the 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) in over 600 engagements and sieges was a violent and prolonged fight. The northern and western areas of England remained mostly loyal to the king, while Parliament controlled the southeast, including London.

- The defeat at Roundway Down in July 1643 nearly destroyed the Parliamentary army of the Western Association led by Sir William Waller. One of the Parliamentarians' issues was that their best force, the London regiments, was unable to extend service because their absence from the metropolis had a significant influence on commercial activities. As a result, in March 1644, Parliament released additional finances for a permanent army, but this was insufficient.

- The new force engaged in combat on 28 June 1644, at Cropredy Bridge, and on 27 October 1644, in the Second Battle of Newbury.

- In the first combat, Charles I led his army in person and prevailed. In the second, neither side gained an advantage, despite the Parliamentarians' numerical advantage of 2:1.

- These losses prompted a Parliamentarian debate about how to create a permanent and more professional army, a step advocated by Oliver Cromwell, a country gentleman and visionary military leader, in December 1644.

- The war entailed several protracted sieges, so it was important to have a standing army that could fight wherever its commanders saw fit and for as long as it took to win. Another shortcoming was competition among the numerous Association forces, as well as the lack of an overarching command system.

- On 4 February 1645, Parliament authorised the development of a professional fighting army, the New Model Army. The costs were covered by extremely unpopular levies and excise duties. Although the majority of soldiers were volunteers from various existing armies, the aim of 14,400 troops proved unrealistic, necessitating the recruitment of several thousand infantrymen. With these inherent flaws, the Parliamentarians devised a strategy for winning the war but failed to establish long-term authority over their new republic.

PERSONNEL AND WEAPONS

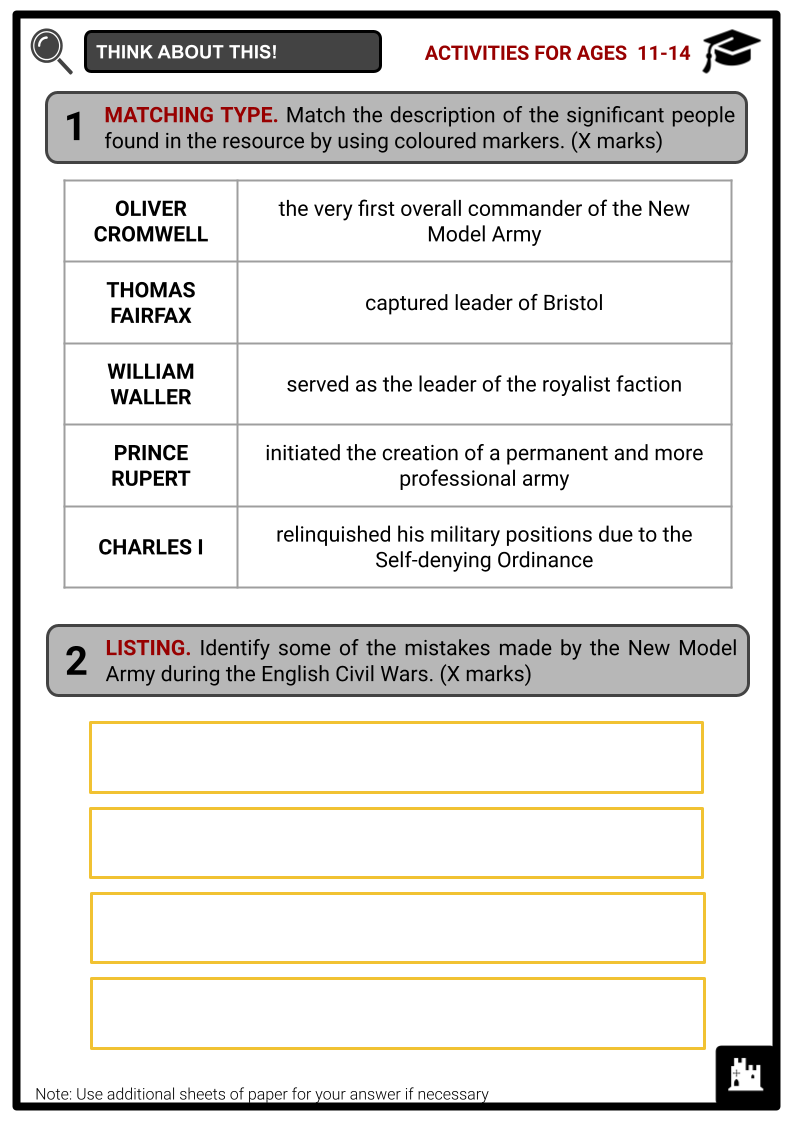

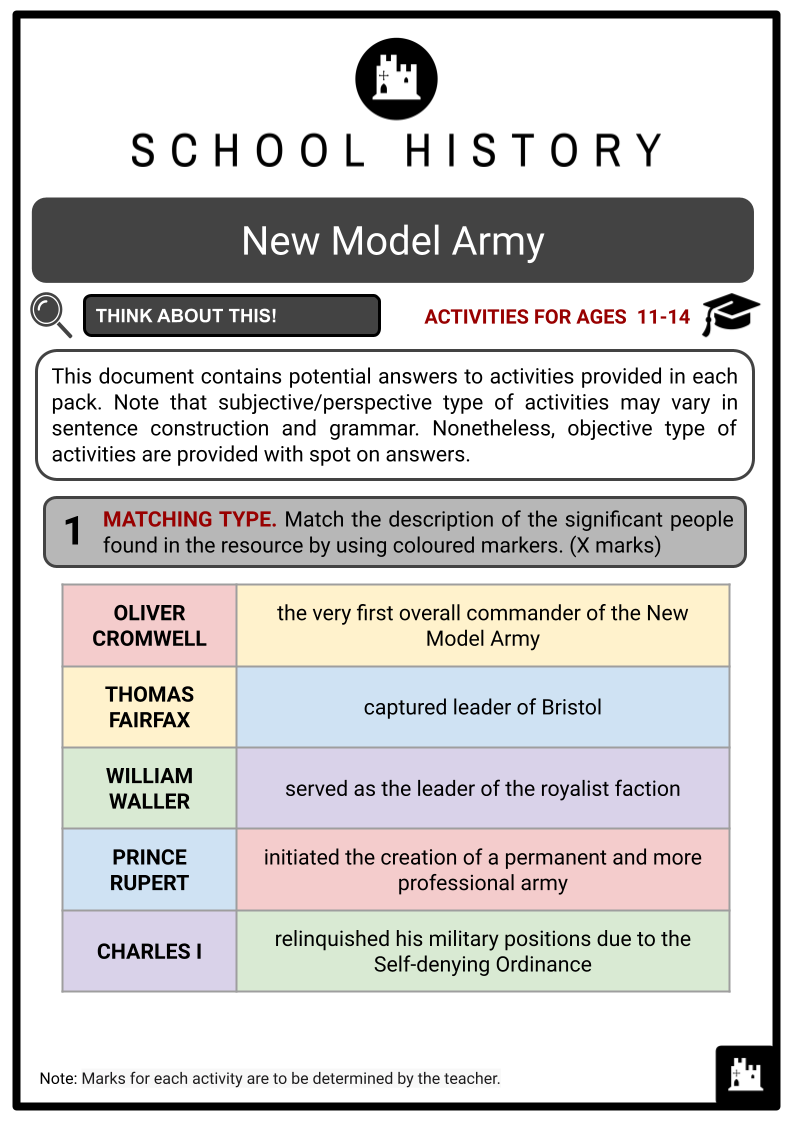

- Parliament's decision to prohibit any of its members from serving as military commanders, which took effect in April 1645, was an important milestone in England's army. The Self-Denying Ordinance removed any commanders who were politically powerful but lacked military competency. The senior officers, as well as the men, had become professionals. Sir William Waller was one among the casualties of those who had to surrender their commands. The very first overall commander of the New Model Army was Sir Thomas Fairfax, a man of both ability and expertise.

- The Model Army was initially made up of 11 cavalry regiments, 12 infantry regiments, 1 dragoon regiment (a combination of cavalry and infantry), and 2 companies of 'firelocks' (artillery and musketeers). Each regiment carried the name of its commanding colonel. Some Parliamentary forces were not immediately integrated into the Model Army. The 24 regiments eventually numbered around 100, depending on the conditions. The increased army was therefore divided into 62 infantry, 28 cavalry, 4 dragoons and several artillery regiments. At its peak, the Model Army had approximately 68,000 troops.

- The military hierarchy consisted of various officers overseeing different branches and aspects of the army, including cavalry, infantry, artillery, logistics and command.

- Infantry regiments typically comprised around 1,200 soldiers, although they rarely operated at full capacity. Companies within regiments were flexible units that could be combined as needed.

- Each regiment had a colonel at the top, followed by a lieutenant colonel, sergeant-major and company captains. Captains led their units, supported by lieutenants, sergeants and corporals.

- Ensigns carried the regiment's colours, while drummers conveyed orders to the troops during battles. Flags were also used to coordinate troop movements.

- The dragoons regiment comprised approximately 1,000 mounted infantry, who dismounted for battle, at least in the early stages of the war. They eventually became regular cavalry. Each horse regiment was divided into 6–8 groups consisting of 60–80 riders. The colonel (or lieutenant-colonel), sergeant-major and captains each led a unit, which was subsequently standardised to 6 units of 100 riders. Cromwell's cavalry force, known as 'The Ironsides', which comprised 14 units, represented the diversity in cavalry composition.

- Artillery was crucial in 17th-century warfare. The Model Army began with 56 cannons, but as time passed, the force grew, particularly with captured enemy reinforcements. To prevent using outdated slow-burning matches that could set off nearby gunpowder, the cannon and its operators were covered by two companies of musketeers equipped with the latest flintlock guns.

- Infantry soldiers were typically clad in Venetian red coats, though with some variations among regiments. They wore cassocks, long coats with buttons, paired with baggy breeches tied at the knee, double-layered stockings and leather shoes. Pikemen donned metal helmets like the morion and breast- and backplates, although body armour became less common as the war progressed.

- Cavalrymen sported buff coats for protection against sword slashes, often layered with long leather coats, and wore zischagge helmets with breast- and backplates for arm protection. Musketeers favoured wide-brimmed felt hats adorned with feathers, while some pikemen adopted similar headgear over helmets. Distinguishing friend from foe by dress alone proved challenging, leading to the adoption of coloured sashes, ribbons, and field signs like exposed coat linings or foliage sprigs. However, such measures didn't always prevent mix-ups on the battlefield.

- Infantry units were predominantly armed with pikes and muskets, with musketeers making up two-thirds of the force.

- During the battle, infantry companies formed tightly packed ranks with musketeers positioned on the flanks, using long pikes and matchlock muskets.

- Musketeers faced challenges with accuracy beyond 100 yards, relying on volley fire for effectiveness.

- Reloading was a slow and meticulous process, involving ramming powder, bullet and wadding down the barrel, priming the lock mechanism, and igniting the match.

- Musketeers carried various equipment including cartridges, powder and priming flasks, bullets and spare matches, requiring protection from wet weather to maintain effectiveness.

- Swords were commonly worn by infantry and cavalry, with gentlemen favouring rapier-like blades and cavalry wielding broadswords.

- Cannons played a vital role in sieges and open battles, coming in various sizes and firing solid balls or shells with impressive range and frequency, contributing to continuous enemy bombardment.

CONTRIBUTION TO WAR AND INFLUENCE

- In June 1645, the Model Army demonstrated its worth at the Battle of Naseby, Northamptonshire. The well-trained and disciplined Parliamentarian cavalry wiped out the Royalists, despite their numerical disadvantage. The victory was swiftly followed by another near Langport, Somerset, against a Royalist force of 7,000. Next, the army's siege powers were tested. Bristol, while under the control of Prince Rupert (King Charles' nephew), was a strategic bastion with its port.

- The Model Army surrounded the city, captured several of its defensive batteries, and successfully negotiated Rupert's capitulation. The Royalists had never received such a blow. A Royalist force was beaten once more in March 1646, at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold. The Model Army had won the conflict, or as it turned out, what has become known as the First English Civil conflict.

- During the Second English Civil War, a Scottish army invaded England to liberate Charles from his hiding on the Isle of Wight. Simultaneously, royalists resurfaced in many isolated places, most notably in Kent and Essex. At the Battle of Preston in 1648, the Model Army triumphed over the combined Scots and English rebels, both in the south under Fairfax and in the north under Cromwell.

- The Model Army had grown so powerful that it could defy Parliament's decision to dissolve it. In December 1648, the army marched against that institution, hoping to seize Presbyterian members of Parliament and demand that their pay arrears be met. The Independents now dominated the army command, and they considered the Presbyterians as significant adversaries to their desires to preach their form of Christianity, rather than partners against the monarchy. The Levellers, radicals who aimed to equalise wealth and expand suffrage, were another faction attempting to enter the army's top leadership. In short, the army was becoming more of a political tool than a military one.

- Meanwhile, Charles was charged with treason and executed in January 1649. Still, the war had not ended. In 1650, there was a large revolt in Ireland against the regicide, and Cromwell led 12,000 soldiers from the Model Army to put it down brutally.

- Still not done, the Scots backed Charles I's son, another Charles, and the Model Army was deployed north again.

- Fairfax, concerned about how the war was progressing, declined to head the army, so Cromwell took over as commander-in-chief.

- Cromwell led 16,000 soldiers to a decisive victory at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, capturing Edinburgh Castle on Christmas Eve.

- In September 1651, Cromwell's Model Army beat a Scottish invasion army at Worcester. The Civil Wars had been a harsh war, but they had finally come to an end.

- The Model Army's political authority is demonstrated by the reduction in size and power of Parliament, as well as the nomination of its commander, Cromwell, as Lord Protector of England, in December 1653. The new Republic was divided into 12 military districts, each headed by a major general. Following Cromwell's death, Parliament agreed to reinstate the monarchy in May 1660. The Republic was short-lived, but its New Model Army, which was largely disbanded by the new monarch Charles II of England, laid the groundwork for the professional British Army's long-term success over the next 250 years.

Image Sources

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the New Model Army?

The New Model Army was a professional military force formed in 1645 during the English Civil War.

- Why was the New Model Army created?

The New Model Army was created to centralise Parliamentarian military power and to counter the Royalist forces during the English Civil War. It aimed to replace the decentralised and amateurish militia-based system that had previously existed.

- Who led the New Model Army?

The New Model Army was initially led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, with Oliver Cromwell as his second-in-command. After Fairfax retired in 1650, Cromwell became the army's commander-in-chief.