Catholic Emancipation Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Catholic Emancipation to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Initial Reliefs

- Acts of Union 1800

- Campaign for Catholic Emancipation

- Impact of the Catholic Emancipation

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Catholic Emancipation!

The Catholic Emancipation Act, also known as the Roman Catholic Relief Act, was approved by the United Kingdom (UK) Parliament on 24 March 1829 and gained Royal Assent on 13 April 1829. It was the culmination of the nation’s Catholic Emancipation process. Ireland repealed the Test Act of 1673 and the remaining Penal Laws that had been in effect since the Disenfranchising Act of the Irish Parliament of 1728.

INITIAL RELIEFS

- The Quebec Act of 1774 eased some limitations on Roman Catholics in Canada. It was termed as one of the Intolerable Acts and, in October 1774, was criticised in the Petition to the King, a petition sent to George III in October 1774 by the First Continental Congress of the Thirteen Colonies. The Intolerable Acts were a set of five punitive legislations enacted in 1774 by the British Parliament in response to the Boston Tea Party. This American political and mercantile protest happened on 16 December 1773.

- The first Relief Act, known as the Papists Act, was passed in Great Britain and separately in Ireland in 1778; subject to an oath renouncing Stuart’s claims to the throne and the civil jurisdiction of the pope, it allowed Roman Catholics to own property and inherit the land. Reactions to this included rioting in Scotland in 1779 and the Gordon rioting in London on 2 June 1780.

- An Act of 1782 provided more aid by establishing Roman Catholic schools and bishops. The Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1791 provided for the free practice of Catholicism but with significant restrictions to make Catholicism less apparent in the communities where it was practised.

- The Irish Parliament passed the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1793, granting Catholics the right to vote. Because the electoral franchise was primarily controlled by property at the time, this remedy provided votes to Roman Catholics who owned land worth £2 per year. They also began to acquire access to several middle-class professions that had previously been closed to them, such as the legal profession, grand jurors, universities, and lesser posts in the army and court.

Portrait depicting the Gordon Riot

ACTS OF UNION 1800

- The measures of Union 1800 were simultaneous measures passed by the Parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland that merged the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, which were previously in personal union, to become the merged Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The legislation went into effect on 1 January 1801, and the first meeting of the combined Parliament of the United Kingdom was held on 22 January 1801.

Passage of the Act

- The Parliaments of the UK and Ireland passed complementary legislation. The Irish Parliament had obtained significant legislative freedom under the 1782 Constitution.

- Many members of the Irish Parliament, particularly Henry Grattan, were fiercely protective of that autonomy, and a motion for unification was constitutionally rejected in 1799. Only Anglicans were permitted to sit in the Irish Parliament, even though most Irish people were Roman Catholic, with many Presbyterians in Ulster.

- Roman Catholics recovered the ability to vote under the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793 if they owned or rented property worth £2 per year. Wealthy Catholics passionately favoured union, hoping for quick religious emancipation and the opportunity to vote in Parliament, which did not materialise until the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829.

- Due to the uncertainties brought by the French Revolution of 1789 and the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the elites of Great Britain desired the union. If Ireland embraced Catholic emancipation, a Roman Catholic Parliament could break away from Britain and collaborate with the French, but the same measure within the UK would rule that out.

- Furthermore, when the Irish and British Parliaments established a regency during King George III’s leadership, the Prince Regent was given various powers. Due to these reasons, the UK decided to seek the merger of both kingdoms and parliaments.

- The eventual passing of the Act in the Irish Commons relied on a about 16% relative majority, gaining 58% of the votes, and comparable in the Irish Lords, in part by bribery with the distribution of peerages and honours to critics to gain votes, according to contemporary reports.

- The first effort had been defeated by 109 votes to 104 in the Irish House of Commons, but the second vote in 1800 passed by 158 votes to 115.

CAMPAIGN FOR CATHOLIC EMANCIPATION

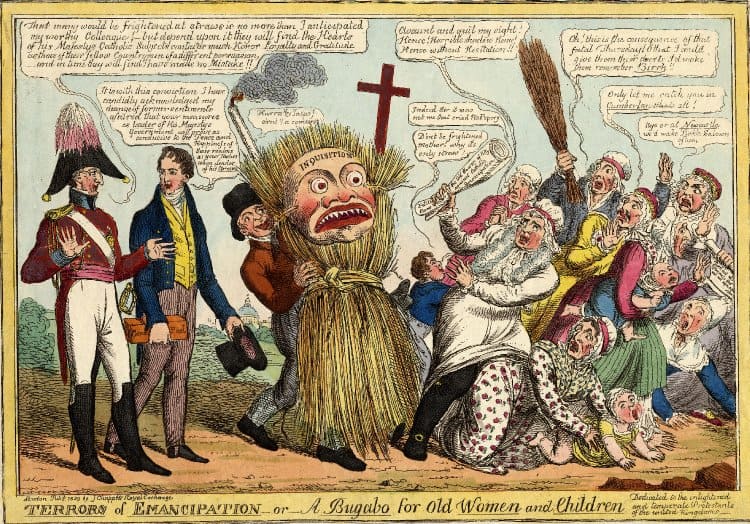

- During 1828 and 1829, Daniel O’Connell, organiser of the Catholic Association, spearheaded the movement for Catholic emancipation in Ireland, although many others were involved, both supporters and oppositions. From 1822 to 1828, as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, laid the groundwork for the Roman Catholic Emancipation Bill.

- Wellesley’s approach was one of reconciliation, aiming to restore Roman Catholics’ civic rights while respecting Protestants’ rights and interests. When riots threatened the peace, he used force to restore law and order, and he prohibited public agitation by the Protestant Orange Order and the Roman Catholic Society of Ribbonmen.

- Bishop John Milner was an English Roman Catholic bishop and writer who, until he died in 1826, was very engaged in advocating Roman Catholic emancipation. He was a crucial figure in anti-Enlightenment thought in England and Ireland. He was instrumental in defining the Roman Catholic response to prior attempts in Parliament to pass Roman Catholic emancipation measures.

- Meanwhile, after a slow start, Ulster Protestants organised to oppose emancipation. After the arrival of O’Connellite Jack Lawless, who arranged a series of pro-emancipation meetings and activities across Ulster, Protestants of all classes began to organise by late 1828.

- His action inspired Protestants to create clubs, distribute tracts, and organise petition drives. However, the Protestant protests were poorly sponsored and managed, and they had no critical support from the British government.

- Following the release of Roman Catholic Relief, the Protestant opposition split along class lines. The aristocracy and gentry fell silent while the middle and working classes marched in Orange parades to celebrate Protestant rule over Ulster’s Catholics.

Parliamentary Elections (Ireland) Act 1829

- Catholics’ civil and political rights in the UK were restricted until the late 1820s, and they were not allowed to sit in Parliament. Daniel O’Connell, an Irish Catholic lawyer, was elected to the House of Commons in 1828. With the assistance of the home secretary, Robert Peel, and the Lord Chancellor, Lord Lyndhurst, the prime minister, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, chose to approve the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, allowing O’Connell to assume his seat.

- The Parliamentary Elections (Ireland) Act 1829, often known as the Irish Franchise Act 1829, was enacted by the UK Parliament in 1829. It limited the suffrage to elect knights of the shire in county constituencies in Ireland to individuals with a freehold of £10, thereby disenfranchising forty-shilling freeholders.

- It obtained royal approval on the same day the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829 granted Catholics the right to vote in Parliament.

- The legislation was expected to reduce the electorate from 215,000 to 40,000 people. Shortly after, the county franchise was enlarged again by the Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1832, which raised the franchise to roughly 60,500.

IMPACT OF THE CATHOLIC EMANCIPATION

- Jonathan Charles Douglas Clark, a British historian, described England before 1828 as a country in which the vast majority of people believed in the divine right of kings, the validity of hereditary nobility, and the rights and privileges of the Anglican Church.

- Clark’s interpretation focused on the system, which was intact not until the passage of the Catholic Emancipation in 1829. The Act overturned the premise that Britain was a protestant nation both de jure (legally recognised) and de facto (practices that exist in reality); however, the Act of Settlement (1701) prohibiting the queen from being a Catholic or marrying a Catholic remained in force. However, Parliament was now open to both protestant and Catholic dissenters and was no longer the established church’s political forum. Certain priests were shocked when such a heretical organisation attempted to legislate for the Church of England. The unity of church and state, enshrined in the 1689 Revolution Treaty, had been ruptured.

- As a result, a Roman Catholic heir can only inherit the throne by shifting religious allegiance. Since the Papacy recognised the Hanoverian monarchy in January 1766, no immediate royal heirs have been Roman Catholics, which is prohibited under the Act. The line of succession to the British throne includes many more distantly related prospective Roman Catholic successors. Section 2 of the Succession to the Crown Act 2013, as well as comparable provisions in the laws of other Perth Agreement signatories, enables such an heir to marry a Roman Catholic. The Succession to the Crown Act 2013 is a UK Parliament Act that amended the statutes of succession to the British crown by the 2011 Perth Agreement, which was made in Australia in 2011 by the prime leaders of the sixteen Commonwealth realms, all of which recognised Elizabeth II as their head of state.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is Catholic Emancipation?

Catholic Emancipation refers to the series of legislative changes in the UK during the 19th century that aimed to grant civil and political rights to Catholics, particularly the right to sit in the Westminster Parliament and hold public office.

- What was the importance of Catholic Emancipation?

The importance of Catholic Emancipation lies in its pivotal role in promoting religious tolerance and expanding civil rights in the UK. The reforms were part of broader 19th-century constitutional changes, reducing religious strife, shaping a legacy of religious freedom, and influencing global discussions on liberty and equality.

- Who was a key figure in advocating for Catholic Emancipation?

Daniel O'Connell, an Irish political leader, was a key figure in the movement for Catholic Emancipation. His efforts, including winning a by-election in County Clare in 1828, put significant pressure on the British government to address the issue.