Coup de Brumaire 1799 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Coup de Brumaire 1799 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- Course of the Coup

- Day 1: 18 Brumaire

- Day 2: 19 Brumaire

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Coup de Brumaire 1799!

The Coup de Brumaire or Coup d'Etat of 18 Brumaire elevated Napoleon Bonaparte to First Consul of France. Most historians agree that it put an end to the French Revolution and paved the way for Napoleon to be crowned emperor. The French Consulate took the place of the Directory following this non-violent coup d'état. This happened on 9 November 1799, which according to the short-lived French Republican calendar system was 18 Brumaire, Year VIII.

BACKGROUND

- Power conflicts between groups in Paris characterised the French Revolution in 1799, with the French Directory at the centre. The struggle for power between the right-wing royalists and the left-wing neo-Jacobins threatened to fundamentally change the direction of the Revolution. In the War of the Second Coalition against European nations, France participated as well. The French people, weary of the unrest after a decade of revolution, craved stability and tranquillity, even if it meant giving up some liberties. Even though the Directory was intended to be a separation of powers, it soon became apparent that it was unable to deliver the needed stability.

- The Directory introduced a two-chambered parliament: the Council of 500 proposed legislation, while the Council of Ancients accepted or vetoed it.

- Executive power was held by a council of five Directors chosen by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the Council of 500.

- To prevent long-term power, one Director had to resign each year through a drawing of lots.

- Corruption and political intrigue plagued the Directory, and most Directors were ineffective politicians.

- In 1797, the moderate Directors staged the Coup of 18 Fructidor to maintain power, nullifying elections and arresting conservative deputies.

- In 1798, the Directors disqualified undesirable candidates to preserve a moderate majority.

- In 1799, the neo-Jacobins won a majority in the elections and staged the Coup of 30 Prairial, forcing some moderate Directors to resign.

- Multiple coups in quick succession signalled instability, and the future of the Republic was uncertain.

- Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès had never been fond of the Directory. When he was once again offered the job in May 1799, he accepted – not out of any change of heart, but because he understood that the time was right to destroy the Directory and that the best way to do it was from within – despite having previously turned down an offer to serve as one of the original five Directors in 1795 because he was primarily opposed to the Constitution of Year III.

- Political change was nothing new to Sieyès. He had been a prominent member of the Third Estate when it established the National Assembly in 1789, sparking the Revolution. He then discovered that there were plenty of influential men looking to gain financially from the Directory.

- Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, an ambitious man who lost his position as foreign minister, sought to profit from the Directory's downfall.

- Jean-Jacques de Cambacérès, the flamboyant justice minister, agreed to finance the plot against the Directory.

- Joseph Fouché, the minister of police, had a network of spies in Paris and had never been on the losing side of a coup.

- Roger Ducos, another Director aligned with Sieyès, and Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon's younger brother and a deputy, joined the conspiracy.

- The conspirators needed military support, referred to as Sieyès's 'sword', to ensure the success of their plot.

- The 'sword' in question was the young, appealing and brave General Barthélemy Joubert, who had already proven valuable to Sieyès during the Coup of 30 Prairial. Joubert was given command of the Army of Italy by Sieyès and Talleyrand in early August so he could score a few more wins before the coup was set to begin. Joubert unfortunately died at the Battle of Novi on 15 August just a few days after taking command.

- Sieyès was compelled to look for a new 'sword' that would be well-liked enough to win the army's and the French people's support.

- Few of the potential candidates were likely to help Sieyès achieve her objectives.

Napoleon Bonaparte - Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, a hero of the Battle of Fleurus, flatly refused to aid the coup while promising not to obstruct it either. Jean Bernadotte was too much of a Jacobin.

- General Jean-Victor Moreau, who was wary of getting engaged in politics, was the next target of Sieyès's courtship.

- Napoleon Bonaparte was, after all, the most obvious choice. Napoleon, the renowned conqueror of Italy, had spent the previous year fighting in the Middle East. Although his campaign in Egypt and Syria had ultimately been unsuccessful, his successes along the way, including the Battle of the Pyramids, had captivated the public's attention in France.

- On 16 October he landed in Paris and was welcomed as a victorious hero. Talleyrand persuaded Sieyès to offer Napoleon a position in the conspiracy, despite the fact that Sieyès loathed Napoleon personally and secretly thought Napoleon ought to have been executed for leaving his troops in Egypt. After considerable deliberation, Napoleon agreed, and the two men gathered in Lucien Bonaparte's home to formulate the plan of action.

COURSE OF THE COUP

- The men's scheme called for a two-day coup. The first step was to remove the Directory from Paris because if it remained there, there was a chance that the neo-Jacobins would mobilise the city's populace to defend the government.

- In order to inform them that a Jacobin plan had been uncovered and that the legislature would need to convene the following day at the palace of Saint-Cloud for its own safety, Sieyès was to convene an emergency meeting of the Council of Ancients on the first day. Sieyès and Ducos would resign from their positions as Directors while using threats and bribes to pressure the other three Directors into doing the same.

- On the second day, Napoleon planned to visit both legislative chambers and inform them that the Republic was in danger due to Jacobin plots and that the only way to save it was to repeal and replace the Constitution of Year III. A provisional government, led by Sieyès, would then be established to implement a new constitution.

- The plan to overthrow the Directory began on 7 November 1799 (16 Brumaire).

- The conspirators decided to stretch the coup over two days, which carried risks of exposing the plot.

- Suspicion arose among some members of the Ancients, causing a delay to the plot.

- The new designated start date for the coup was 9 November (18 Brumaire).

- Napoleon dined with generals Bernadotte, Jourdan and Moreau on the night of 9 November to persuade them to join the plot.

- Moreau agreed to help by arresting the Directors in the Luxembourg palace, but Bernadotte and Jourdan refused.

- Napoleon secured the support of Colonel Horace Sebastiani and the 9th Dragoon Regiment.

- The stage was set for the coup to proceed.

DAY 1: 18 BRUMAIRE

- The National Guard and the 17th District commanders gathered at Napoleon's residence on the rue de la Victoire at 6am on 9 November. Napoleon pretended to be the defender of the government he was going to overthrow by dressing as a civilian, outlining the dangerous predicament the Republic was in, and requesting their allegiance. At the Tuileries Palace, where the Council of Ancients had gathered, Lucien Bonaparte informed them of the Jacobin plot.

- The Ancients had to formally shift the following day's session from the Tuileries to Saint-Cloud, and Napoleon was given command of all local armed troops under two decrees that the Ancients were forced to sign for their own protection. In simple terms, those Ancients who were thought to be most likely to disagree with the decrees were not informed of and did not attend the emergency meeting. To personally reassure the Ancients, Napoleon got into his general's uniform at 10am and rode to the Tuileries.

- Later that morning, Sieyès and Ducos quit their positions as Directors and persuaded the other three Directors to follow suit. After Talleyrand offered him a bribe, Paul Barras gave in to his first reluctance and departed Paris right away, flanked by cavalry to make sure he did not change his mind. The other two Directors, Louis-Jérôme Gohier and Jean-François Moulin, put up more of a fight. Early on day two, Moreau's forces captured them and forced them to quit. The success of the coup depended on Napoleon's ability to persuade the two chambers to dissolve themselves since the head of state had been essentially decapitated.

DAY 2: 19 BRUMAIRE

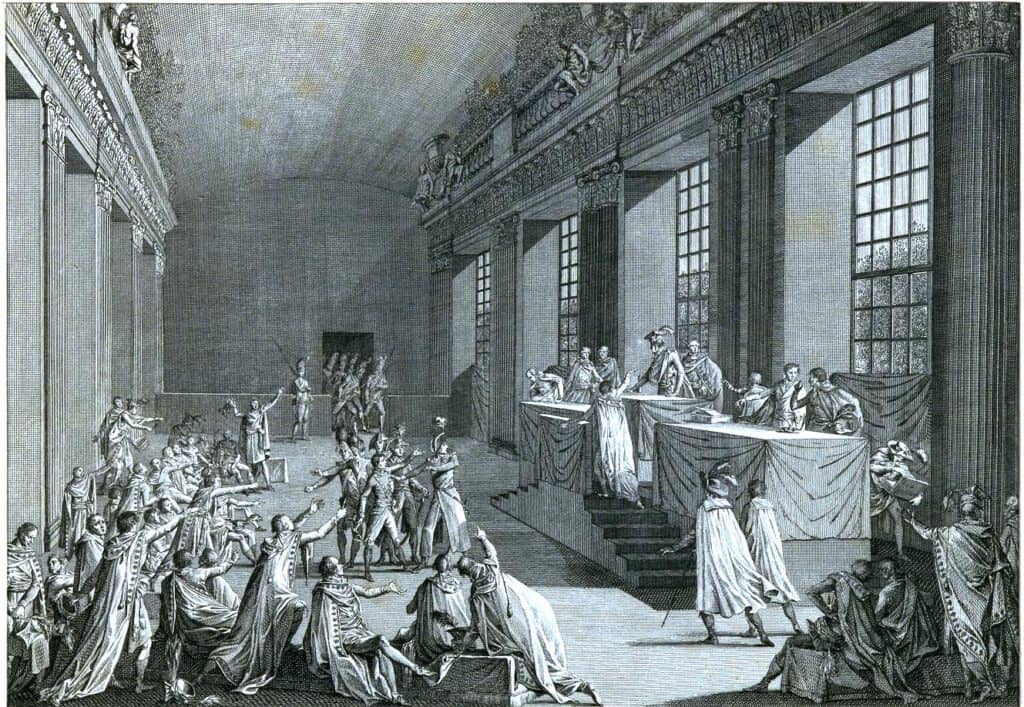

- Napoleon entered the chamber at Saint-Cloud where the Council of Ancients was convened early on 10 November (19 Brumaire), flanked by devoted grenadiers. By this time, the majority of the deputies believed that a coup d'état was taking place rather than a Jacobin plan. Napoleon brought up the recent coups in his speech and said that the constitution needed to be replaced because it had already been broken and no longer had anyone's respect. The Council of 500 had convened in the Orangery of the palace, so Napoleon and his grenadiers made their way there.

- The neo-Jacobin-dominated Council of 500 reacted hostilely to Napoleon's presence during the coup.

- Deputies expressed outrage at seeing men in uniform at a government meeting.

- Despite the uproar, Napoleon made his way to the rostrum and declared an end to factionalism.

- Lucien, the president of the Council, tried to restore order, but some deputies surrounded Napoleon and physically confronted him.

- Grenadiers escorted Napoleon out of the chamber while a motion to declare him an outlaw was proposed.

- Lucien managed to maintain a lawful session and allow the vote to proceed by holding the president's chair.

- Napoleon was reportedly shaken by the situation, showing signs of fear and trembling.

- Lucien left the Orangery and convinced the soldiers guarding the councils that Jacobin deputies, bribed by English gold, were threatening Napoleon's life.

Lucien Bonaparte - Lucien theatrically pointed a dagger at Napoleon's heart and declared he would stab his own brother to protect French liberty. The soldiers, convinced by Lucien's story, cleared out the deputies, leading to some jumping out of windows to avoid arrest.

- Later that evening, Lucien assembled as many pro-coup deputies as he could find. The deputies resolved to suspend both houses of the legislature for four months and to dismiss 61 of the neo-Jacobins from the Council with no resistance in the room. After voting to abolish the French Directory and form a provisional council to draft the new constitution, Lucien adjourned the conference.

AFTERMATH

- After the Council was defeated, the conspirators gathered two commissions, each made up of 25 deputies from the two Councils. Napoleon, Sieyès and Ducos served as the first consuls in the provisional government that the conspirators effectively forced the commissions to declare. The fact that there was no outcry in the streets demonstrated that the Revolution had ended.

- They were chosen on 11 November to serve as the temporary government's three consuls and drafted the constitution. Assuming victory, Sieyès wanted to draft the constitution himself. However, he had miscalculated Napoleon's political clout, and the latter orchestrated a coup inside a coup. Napoleon outwitted Sieyès by using his popularity and the sheer power of his personality. The Constitution of Year VIII, which was ratified on 24 December 1799, was largely the result of work done by Napoleon and his friends.

- Napoleon Bonaparte was appointed First Consul of the Republic's new government, the French Consulate, when Sieyès was made to retire. The majority of the remaining conspirators, including Talleyrand, Cambacérès and Fouché, would later hold influential positions in Napoleon's administration. At first, Lucien concurred, but later he became weary of his brother's authority and fled to Rome in 1804 for self-imposed exile.

- After the appointment, Napoleon declared that the French Revolution was over, a claim that had been made by previous leaders but held true this time.

- Napoleon's leadership promised security and stability, which resonated with the French people, who were tired of the chaos and instability of the revolutionary period.

- Despite his gradual shift towards authoritarianism and his eventual establishment as an emperor, many people embraced Napoleon's rule, seeing him as a source of constancy and order.

- This marked the end of the revolutionary era and the beginning of the Napoleonic Era, characterised by Napoleon's consolidation of power and his influence over France and Europe.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a9/Coup_d%27%C3%89tat_du_18_Brumaire.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Jacques-Louis_David_-_The_Emperor_Napoleon_in_His_Study_at_the_Tuileries_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Bonaparte#/media/File:Fabre_-_Lucien_Bonaparte.jpg

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the Coup de Brumaire in 1799?

The Coup de Brumaire was pivotal in French history on November 9-10, 1799 (18th-19th Brumaire in the French Republican calendar). It marked the overthrow of the French Directory government and the establishment of the Consulate, led by Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Who was involved in the Coup de Brumaire?

The Coup de Brumaire involved a group of French political and military leaders. Bonaparte and his brother Lucien Bonaparte and Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès orchestrated the coup.

- What were the consequences of the Coup de Brumaire?

The Coup de Brumaire had significant consequences for French politics and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Directory government was dissolved, and the Consulate was established, with Napoleon as the First Consul. The Coup de Brumaire shifted from the revolutionary period to a more authoritarian rule, setting the stage for Napoleon's dominance in European affairs for the next decade.