Pontiac's Rebellion Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Pontiac's Rebellion to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Origin of the Pontiac’s Rebellion

- Outbreak of the Pontiac’s Rebellion

- British Response

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Pontiac’s Rebellion!

Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763–1766) was an armed war between the British Empire and Indigenous nations who spoke Algonquian, Iroquoian, Muskogean and Siouan. The violence, also known as ‘Pontiac’s War’ or ‘Pontiac’s Uprising’, represented an unprecedented pan-Indian resistance to European colonisation in North America, in which Indigenous nations challenged the British Empire’s attempts to impose its will and abrogate Indigenous sovereignty.

ORIGIN OF THE PONTIAC’S REBELLION

- The origins of the Pontiac’s Rebellion can be traced back to the political aftermath of the Seven Years’ War. Following the British triumph in 1763, the empire aspired to include former French and Spanish lands, including Canada, Florida and the Great Lakes, into its American dominion. At the same time, the English inherited a complex structure of alliances with the Indigenous nations of those regions, prompting imperial authorities to consider whether Indigenous peoples were subjects of empire or sovereign polities.

- Finally, Jeffrey Amherst, the governor-general of North America, summed up British attitudes towards Indigenous peoples. Amherst was convinced that the only proper method of treating Indigenous peoples was to keep them in fair subjection.

- Most egregiously, Amherst ended the political practice of gift-giving, which he saw as an unnecessary cost. However, in most Indigenous civilisations, gifting was culturally significant and strengthened political relationships between the two parties.

- The value of gift-giving in Indigenous peoples’ cultures cannot be emphasised. The exchanging of presents was and continues to be a way to express respect, friendship and honour for someone. Gifts were physical representations of the bond between two parties. When the new British residents of French forts failed to create a relationship with their Indigenous neighbours by exchanging presents, it was viewed as an insult to the Indigenous people and strained relations between the British and Indigenous peoples.

- As a result, Amherst breached the expectations of the Indigenous peoples, thereby severing possible ties between the British Empire and Indigenous nations. In addition, colonists encroached on Indigenous areas after the battle, imposed trade restrictions, and stationed English troops in the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley. According to David J Silverman, a professor at George Washington University, Indigenous nations such as the Ottawa and Iroquois claimed that these steps made it appear as if the English intended to exterminate them.

How were the Indigenous nations involved in the Pontiac’s Rebellion?

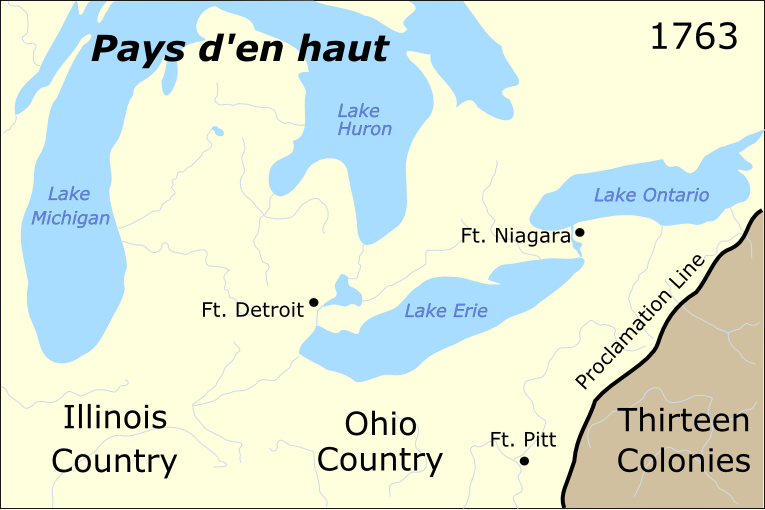

- Indigenous nations involved in the Pontiac’s War lived in a loosely defined region of New France known as the pays d’en haut or the upper country, which France claimed until the Paris Peace Treaty of 1763. Indigenous peoples of the pay d’en haut came from various Indigenous nations. These nations were linguistic or ethnic groups of anarchic villages, not centralised political forces. No single chief spoke for the entire tribe, and no nations worked together.

Three basic groups of pay d’en haut:

- Indigenous nations of the Great Lakes region: Ojibwes, Ottawas and Potawatomis, who spoke Algonquian languages, and Hurons, who spoke an Iroquoian language.

- Indigenous nations from eastern Illinois Country: Miamis, Weas, Kickapoos, Mascoutens and Piankeshaws.

- Indigenous nations of the Ohio Country: Delawares (Lenape), Shawnees, Wyandots and Mingos.

- Outside of the pays d’en haut, the prominent Iroquois did not participate in the Pontiac’s Rebellion because of their Covenant Chain relationship with the British. The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties forged in the 17th century, primarily between the Iroquois Confederacy and the British colonies in North America, with additional Indigenous nations joining.

- However, the Seneca nations, the westernmost Iroquois nation, had grown dissatisfied with the arrangement. Senecas sent war letters to the Great Lakes and Ohio Country tribes in 1761, urging them to band together to drive out the British. When the battle finally broke out in 1763, many Senecas acted quickly.

- Land was also a factor in the outbreak of the Pontiac’s Rebellion. While the French colonists had always been few, there appeared to be an endless supply of settlers in the British territories.

- Shawnees and Delawares in the Ohio Country were displaced by British colonists in the east, which prompted their participation in the conflict. Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region and the Illinois Country had not been significantly impacted by white settlement, although were aware of the experiences of other nations in the east.

- Concurrent with these events was the spread of a rejuvenation movement by the Delaware Prophet, Neolin. Neolin, burdened with a vision from the Master of Life, expressed his conviction that Indigenous peoples had become unduly dependent on Europeans for their livelihoods, particularly in terms of the tools and weapons they used daily.

- In addition, alcohol harmed Indigenous civilisations, missionaries endangered the ways of life of Indigenous people, and colonists trespassed on their territory. Neolin’s message was likewise a synthesis of Delaware and Christian traditions, motivated by a millenarian belief that the world was on the verge of ruin unless they moved against the European danger. After that, Neolin pledged that their former habits and lives would return and flourish.

- It did not take much to persuade officials like Ottawa’s chief, Pontiac. According to Colin Gordon Calloway, a British-American historian, Pontiac pushed other Indigenous nations to eliminate the British on their lands because they aimed to destroy Indigenous culture.

OUTBREAK OF THE PONTIAC’S REBELLION

- In May 1763, Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley launched an onslaught, overrunning Britain’s westernmost outposts, from Fort Edward Augustus to Fort Presque Isle in western Pennsylvania. While historians debate whether the Pontiac’s Rebellion began as a planned or spontaneous attack, the conflict swiftly expanded across Native America.

- From the start, Indigenous strategy was focused on besieging the western forts, cutting off all communications and reinforcements, and subduing the surrounding settler villages. The offensive was largely successful, with only three forts left by the end of June 1763.

- Modern scholars believed that the insurrection spread as word of Pontiac’s acts in Detroit circulated throughout the pays d’en haut, prompting discontented Indigenous nations to join the revolt. The attacks on British forts did not coincide – most Ohio Indians did not join the war until nearly a month after Pontiac began the siege of Detroit.

- The news of the siege circulated swiftly among the Indigenous nations, inspiring additional attacks on British forts and settlers. In May 1763, the Wyandot nations grabbed Fort Sandusky, the Potawatomis took Fort Saint Joseph, and the Miami nations seized Fort Miami. In June 1763, an alliance of Ottawas and Ojibwes conquered Fort Michilimackinac by staging a stickball game outside. They chased the ball into the fort, seized weapons smuggled in by a group of Indigenous women, and slaughtered nearly half of the British soldiers.

- Over the following months, the war extended through the backcountry from Virginia to Pennsylvania, resulting in horrendous brutality on both sides. Firsthand accounts of Indigenous peoples’ attacks describe murder, scalping, dismemberment and burning at the stake. As these stories circulated, colonists developed a profound racial animosity for all Indigenous people, prompting retaliatory bloodshed.

- The actions of a group of Scots-Irish settlers from Paxton, Pennsylvania, in December 1763 demonstrate the problematic situation on the frontier. These frontiersmen formed a mob known as the Paxton Boys and attacked a nearby group of Conestoga Susquehannock tribal members. When Pennsylvania Governor John Penn placed the remaining 14 Conestoga in custody in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the Paxton Boys broke into the building and murdered and scalped any Conestoga they saw in the vicinity.

- Although Governor Penn offered a reward for the arrest of any Paxton Boys engaged in the murders, no one ever identified the perpetrators. Some colonists were outraged by the episode. However, as the failure to bring the murderers to justice demonstrates, the Paxton Boys had many more sympathisers than detractors.

BRITISH RESPONSE

- In 1764, British Major General Thomas Gage dispatched two expeditions to the West to quell the insurrection, rescue British prisoners, and apprehend the Indians responsible for the conflict. According to historian Fred Anderson, Gage’s campaign, planned by Amherst, extended the war by more than a year because it focused on punishing Indigenous peoples rather than ending the battle. Gage’s one notable departure from Amherst’s strategy was to let William Johnson, a British official and diplomat, negotiate a peace treaty at Niagara, offering the Indigenous nations the opportunity to end the conflict.

Peace Settlement

- Pontiac’s War continued until 1766. Indigenous nations targeted British forts and frontier villages, killing up to 400 soldiers and 2,000 inhabitants. Though the nations did not win the Pontiac’s War, they successfully changed the British colonial government’s policy towards Indigenous people. The war forced British officials to recognise that peace in the West would necessitate royal protection of Indigenous territories and stringent regulation of Anglo-Native economic activity. During the conflict, the British Crown issued the Royal Proclamation Line of 1763, establishing the Appalachian Mountains as the border between Indigenous territories and British possessions.

AFTERMATH

- The Pontiac’s Rebellion had far-reaching consequences, as it coincided with the end of the Seven Years’ War. The conflict demonstrated that coercion was ineffective for imperial rule. Still, the British government continued to use it to consolidate authority in North America, most notably through the many taxing Acts imposed on their colonies. Furthermore, the prohibition against Anglo-American settlement in Indian country, particularly the Ohio River Valley, provoked outrage among colonists, who saw it as their right.

- The Pontiac’s Rebellion revealed to Indigenous people the potential for pan-tribal collaboration in resisting Anglo-American colonial development. Although the struggle split tribes and communities, it also saw the first extensive multi-tribal resistance to European colonisation in North America and the first fight between Europeans and Native Americans in which the Indigenous people were not ultimately defeated.

- The Proclamation of 1763 did not prevent British colonists and land speculators from pushing westward. As a result, Indigenous nations had to create new resistance forces. Beginning with the Shawnee conferences in 1767, leaders such as Alexander McGillivray, Blue Jacket, Joseph Brant and Tecumseh attempted to form confederacies to renew the resistance efforts of the Pontiac’s Rebellion in the following decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Pontiac, and what role did he play in the rebellion?

Pontiac was an Ottawa war chief who emerged as a leader in the resistance against British rule. He played a central role in organising the tribes and leading military actions.

- What was the cause of Pontiac's Rebellion?

Pontiac's rebellion was sparked by Indigenous people's discontent with British policies, including the imposition of new taxes, restrictions on trade, and the encroachment of settlers onto Indigenous lands.

- What were the major battles or conflicts during Pontiac's Rebellion?

Some significant battles include the Siege of Fort Detroit, the Battle of Bushy Run, and the Battle of Bloody Run.