Spencer Perceval Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Spencer Perceval to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life of Perceval

- Perceval’s Married Life and Early Political Career

- Perceval as a Solicitor and Attorney General

- Premiership

- Assassination of Spencer Perceval

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Spencer Perceval!

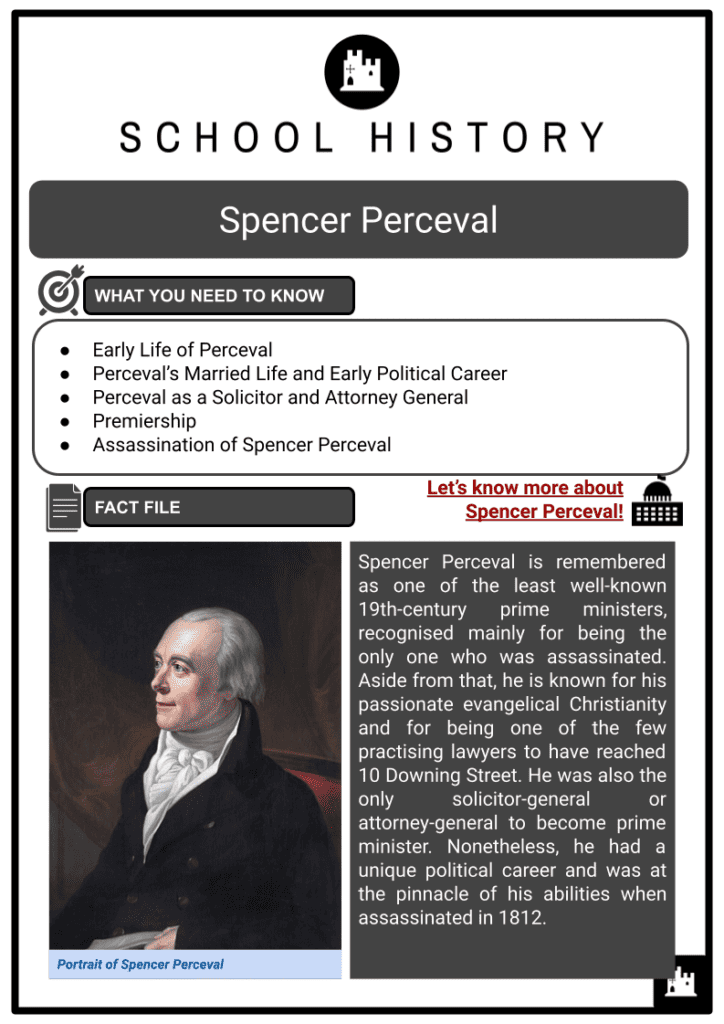

Spencer Perceval is remembered as one of the least well-known 19th-century prime ministers, recognised mainly for being the only one who was assassinated. Aside from that, he is known for his passionate evangelical Christianity and for being one of the few practising lawyers to have reached 10 Downing Street. He was also the only solicitor-general or attorney-general to become prime minister. Nonetheless, he had a unique political career and was at the pinnacle of his abilities when assassinated in 1812.

EARLY LIFE OF PERCEVAL

- Spencer Perceval was born in Mayfair, London. Perceval was the seventh son of John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont and the second son to John’s second wife. Catherine Compton, Baroness Arden, Spencer Perceval’s mother, was the granddaughter of the 4th Earl of Northampton. His father, a political counsellor to King George III and Frederick, Prince of Wales, served briefly as First Lord of the Admiralty in the Cabinet. Perceval spent his early life in Charlton House, which his father had chosen because it was close to Woolwich Dockyard.

- When Perceval was eight years old, his father died. Perceval attended Harrow School, where he was a well-behaved and hardworking student.

- At Harrow, he became interested in evangelical Anglicanism and developed a lasting connection with Dudley Ryder, who would later become the 1st Earl of Harrowby.

- After five years at Harrow, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, with his older brother Charles. Perceval graduated in 1782.

PERCEVAL’S MARRIED LIFE AND EARLY POLITICAL CAREER

- Perceval chose law as his course, studied at Lincoln’s Inn, and was admitted to the bar in 1786. Perceval’s mother passed away in 1783. Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a property in Charlton and met two sisters who lived in Perceval’s old childhood home.

- Sir Thomas Spencer Wilson, the sisters’ father, approved of the marriage of his eldest daughter Margaretta to Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of Parliament and Lord of the Admiralty.

- Perceval, an impoverished Midland Circuit barrister at the time, was instructed to wait until the younger daughter, Jane, was three years old.

- Perceval’s career struggled when Jane turned 21 in 1790, and Sir Thomas was still opposed to the marriage. The couple eloped and married in East Grinstead under a special licence. They shared rooms above a carpet business establishment in Bedford Row before relocating to Lindsey House in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Over the duration of their marriage, Jane and Perceval had a total of 13 children.

How was Perceval’s career after his marriage?

- In 1790, he served as Deputy Recorder of Northampton and as a commissioner of bankrupts.

- In 1791, he was appointed Surveyor of the Maltings and Clerk of the Irons in the Mint, a sinecure paid £119 per year.

- Junior Crown lawyer in the absentia prosecutions of Thomas Paine for seditious libel (1792) and John Horne Tooke for high treason (1794).

- Counsel to the Board of Admiralty in 1794.

- Perceval authored anonymous pamphlets in support of the former Governor General of India Warren Hastings’ impeachment and defence of public order against sedition. These pamphlets drew the attention of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, who offered him the position of Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1795, but Perceval turned down the offer.

- As a barrister, he could earn more money and needed the money to maintain his growing family. In 1796, he was appointed a King’s Counsel, with an annual salary of around £1,000. Perceval earned the title of King’s Counsel at 33, making him one of the youngest ever.

- Perceval’s uncle, the 8th Earl of Northampton, died in 1796. Perceval’s cousin, Northampton MP Charles Compton, ascended to the earldom and took his seat in the House of Lords. Perceval was invited to run in his place for the election.

- Perceval was elected unchallenged in the May by-election but a few weeks later had to defend his seat in a hotly contested general election. Northampton had a thousand electors – every male homeowner not on poor relief got a vote – and a strong radical tradition.

- He delivered many speeches during the 1796–1797 session, always reading from notes. His public speaking abilities had been honed as a law student at the Crown and Rolls debating organisation while still studying. During this time, Perceval didn’t have a salary yet, so he continued his legal career and even served as a senior counsel for the Crown.

- Perceval represented the Castle Ashby interest, Edward Bouverie represented the Whigs, and William Walcot represented the company. Perceval and Bouverie were restored after a contested count. Perceval served as the MP for Northampton. Perceval’s political beliefs were already developed when he took his seat in the House of Commons in September 1796.

PERCEVAL AS A SOLICITOR AND ATTORNEY GENERAL

- Pitt resigned in 1801 after the King and Cabinet rejected his Catholic emancipation plan. Perceval did not feel obligated to join Pitt in opposing Catholic emancipation because he shared the King’s views. During Henry Addington’s premiership, Perceval’s career flourished. In 1801, he was appointed solicitor general, and the following year, he was appointed attorney general. When Addington resigned, he was retained as attorney general, and Pitt formed his second ministry in 1804.

- As attorney general, Perceval was involved in the prosecution of radicals Edward Despard and William Cobbett. Still, he was also responsible for more liberal trade union judgements and improving prisoner transit circumstances to New South Wales.

- Pitt died in 1806, and Perceval resigned as attorney general, refusing to serve in Lord Grenville’s Cabinet. Instead, he became the leader of the Pittite opposition in the House of Commons.

- During his opposition, Perceval used his legal abilities to defend Princess Caroline, the Prince of Wales’ estranged wife, in a controversy. The Princess had been accused of having an illegitimate child, and the Prince of Wales initiated an investigation to obtain evidence for a divorce. The government investigation found that the major claim was false and that the Princess had adopted the child in question, but it was scathing of the Princess’s attitude. The opposition rallied to her rescue, and Perceval became her adviser, writing a 156-page letter on her behalf to King George III.

Perceval as the Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Following Grenville’s resignation, William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, formed a Pittite cabinet and appointed Perceval as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have chosen to stay Attorney General or Home Secretary, and he claimed ignorance of financial matters. He agreed to take the job if the Duchy of Lancaster supplemented the remuneration. Lord Hawkesbury recommended Perceval to the King, noting that he came from an old English family and agreed with the King on the Catholic issue.

- One of Perceval’s first Cabinet objectives was to broaden the previous administration’s Orders in Council, intending to restrict neutral countries’ commerce with France in retribution for Napoleon’s embargo on British trade. He also ensured that Wilberforce’s slave-trade abolition measure, which had not yet reached its final stages in the House of Lords when Grenville’s cabinet fell, did not fall between the two ministries and was rejected in a quick division.

- The Orders in Council were initially intended to restrict commerce with France, but by 1812, they had become a justification to regulate other nations’ slave trades, impeding legal trade. The employment of Orders in Council in this manner substantially harmed the slave trade between the West Indies, other European nations and the Americas.

- As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Perceval was responsible for raising funds to fund the war against Napoleon. This he accomplished in his budgets of 1808 and 1809 by expanding loans at reasonable rates and making savings. As leader of the House of Commons, he faced a strong opposition that questioned the government’s handling of the war, Catholic emancipation, corruption and parliamentary reform.

PREMIERSHIP

- The Duke of Portland’s Cabinet included three future prime ministers, Perceval, Lord Hawkesbury and George Canning, as well as two other renowned statesmen of the 19th century, Lord Eldon and Lord Castlereagh. But Bentinck was a weak leader, and his health was deteriorating. In the summer of 1809, the country was thrown into political turmoil when Canning plotted against Castlereagh, and the Duke of Portland resigned due to a stroke.

- Negotiations to select a new prime minister began: Canning wanted to be a prime minister or nothing. At the same time, Perceval was willing to serve under a third person but not Canning. The remaining Cabinet members decided to invite Lord Grey and Lord Grenville to create an extended and combined administration in which Perceval hoped to be the home secretary. However, Grenville and Grey refused to negotiate, and the King accepted the Cabinet’s choice of Perceval as his new prime minister.

- Perceval’s new ministry was not anticipated to last. It was notably weak in the Commons, where Perceval had just one cabinet member, Home Secretary Richard Ryder, and had to rely on backbenchers for support in debate.

- The government lost four divisions in the first week of the new Parliamentary session in January 1810, one on a motion for an inquiry into the Walcheren Expedition and three on the composition of the finance committee. The Walcheren Expedition was when a military force attempting to conquer Antwerp withdrew due to a disease outbreak on the Dutch coast on the island of Walcheren.

On 30 August, British troops suffering from illness evacuated the island of Walcheren - The government only survived the Walcheren Expedition probe because the expedition’s leader, Lord Chatham, resigned. Sir Francis Burdett, a radical Member of the Parliament (MP), was imprisoned for publishing a letter in William Cobbett’s Political Register criticising the government’s exclusion of the press from the inquiry.

- In 1809, King George III celebrated his Golden Jubilee. By the following autumn, he was showing symptoms of the illness that had led to the threat of a Regency. The thought of a Regency did not appeal to Perceval because the Prince of Wales was known to favour Whigs and despised Perceval for his role during the investigation of the case of Princess Caroline.

- Select committees of the Lords and Commons received evidence from the doctors. Perceval ultimately wrote to the Prince of Wales on 19 December, indicating he planned to present a regency measure the next day. There would be constraints, as with Pitt’s bill in 1788 stating that the Regent’s powers to establish peers and award positions and pensions would be limited for a year, Queen Charlotte would be responsible for the King’s care, and trustees would look after the King’s private property.

- The limits were opposed by the Prince of Wales, who was supported by the opposition, but Perceval got the law through Parliament. Everyone anticipated the Regent to alter his ministers, but he kept his old foe, Perceval. The Regent said he did not want to aggravate his father’s condition.

- On 5 February, the King signed the Regency Bill, the Regent took the royal oath the next day, and Parliament formally opened for the 1811 session. The session was dominated by issues in Ireland, the English economic downturn, the bullion controversy, and military actions in the peninsula.

ASSASSINATION OF SPENCER PERCEVAL

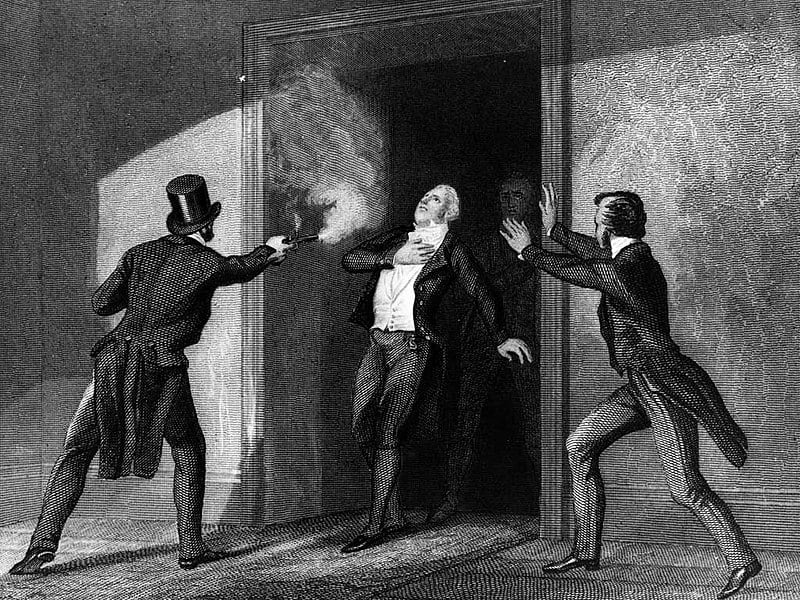

- Perceval was on his way to the inquiry into the Orders in Council around 5:15 pm on the evening of 11 May 1812. A man moved forward, drew a revolver, and shot him in the chest as he entered the lobby of the House of Commons.

- He was comatose when carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, albeit there was still a faint pulse. The pulse had ceased when a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, and Perceval was proclaimed dead.

- At first, it was feared that the assassination might spark an uprising, but it soon became clear that the assassin – who had not attempted to flee – was a guy with an obsessive grudge against the government who had acted alone.

- John Bellingham, the assassin, was a trader who claimed he had been wrongfully imprisoned in Russia and was due to receive compensation from the government, but all of his pleas had been denied.

Portrait depicting the assassination of Perceval as per the impression of the artist

Who was John Bellingham?

- In 1804, Bellingham returned to Archangel with Mary and their young boy to oversee a huge commercial endeavour. With his business concluded, he intended to return home in November but was imprisoned due to an alleged outstanding obligation. This developed due to losses suffered by a business associate for which Bellingham was held accountable.

- Bellingham denied any responsibility for the debt, believing that his incarceration was an act of vengeance by prominent Russian businessmen who mistakenly believed he had thwarted an insurance claim for a lost ship. With the problem still unresolved, Bellingham got passes for himself and his family to travel to St Petersburg, Russia’s capital. As they prepared to leave in February 1805, Bellingham’s pass was cancelled. Mary and the infant were allowed to continue, but he was caught and imprisoned in Archangel.

- When he sought assistance from Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, the British ambassador in St Petersburg, the situation was handled by the British consul, Sir Stephen Shairp, who notified Bellingham that he could not intervene because the disagreement involved a civil debt. Bellingham was imprisoned in Archangel until November 1805, when a new city governor ordered his release and permitted him to join Mary in St Petersburg. With limited success, Bellingham toiled for 18 months to reestablish his commercial career. Mary kept working as a milliner. The fact that he was still uncompensated bothered him.

What happened to Bellingham after he shot Perceval?

- Bellingham sat calmly on a bench during the chaos when Perceval was led into the speaker’s quarters. As it was, a witness to the shooting recognised Bellingham, who was apprehended, disarmed, manhandled and searched. He stayed cool, surrendering to his captors without a fight. When asked to justify his conduct, Bellingham said he was correcting a government denial of justice. The makeshift court was presided over by MPs who also functioned as magistrates, who listened to eyewitness statements and issued orders for Bellingham’s premises to be inspected for additional evidence of his motivation.

- Meanwhile, Bellingham remained undeterred. He ignored the cautions about self-incrimination and instead calmly stated why he had committed such an atrocity. He went on to explain to the court how he had been mistreated and how he had exhausted all other options before making this decision. He displayed no remorse. By 8 pm, he had been charged with the Prime Minister’s murder and was held in prison awaiting trial.

- Bellingham, a man dedicated to justice, went after the man at the top, Perceval. Liverpool was among the cities severely damaged by the Orders in Council policy. Bellingham resided in Liverpool and witnessed firsthand the economic downturn that Perceval was responsible for. Perceval’s death and the following annulment of the Orders in Council would have benefited merchants at home and abroad.

- Perceval died after only a few years as prime minister, leaving behind a wife and 12 children (only 12 out of 13 survived until adulthood). On the 16 May, he was buried privately in Charlton, and two days later, Bellingham was found guilty and hung.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Spencer Perceval?

Spencer Perceval was a British statesman who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1809 until his assassination in 1812. He is notable for being the only British Prime Minister assassinated.

- What were Spencer Perceval's significant contributions as Prime Minister?

Perceval's tenure as Prime Minister was marked by his efforts to stabilise the British economy during the Napoleonic Wars. He implemented various economic reforms and supported the abolition of the slave trade. He also strengthened the Bank Charter Act, which aimed to regulate the issue of banknotes.

- How did Spencer Perceval die?

Spencer Perceval was assassinated on 11 May 1812 by John Bellingham, a merchant with a personal grievance. Perceval was shot and killed in the lobby of the House of Commons in London.