War of the Austrian Succession Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the War of the Austrian Succession to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Historical Background

- War of Jenkins’ Ear: 1739 - 1748

- First Carnatic War

- First Silesian War

- Second Silesian War

- Jacobite Rising of 1745

- Battles in 1746 - 1747

- Aftermath of the War of Austrian Succession

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the War of the Austrian Succession!

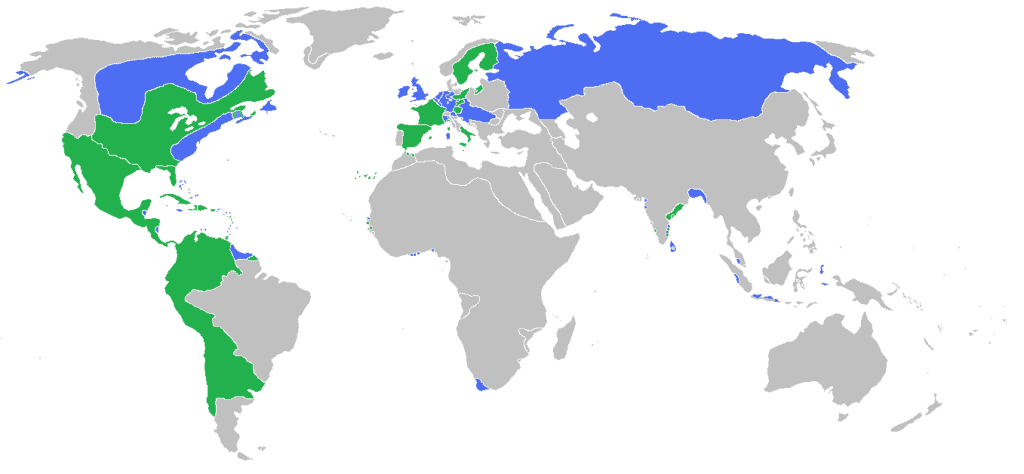

The War of the Austrian Succession arose from a disagreement between Prussia, a militaristic and emerging German state, and Austria, the seat of the Hapsburg Empire. Charles VI, Emperor of Austria, had died without a son, leaving his empire to his daughter Maria Theresa. Prussian Emperor Frederick II saw this as an opportunity and invaded Silesia. Almost every power in Europe was involved because of complicated pre-existing ties. France and Britain, in particular, eagerly entered the war, less to aid their respective allies and more to compete for domination in their American and Asian colonies.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- Charles VI of the Habsburg dynasty issued the Pragmatic Sanction proclamation in 1713. Its goal was to ensure that a daughter might inherit the Habsburg hereditary estates. The Archduke of Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Croatia, the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Italian territories ceded to Austria by the Treaty of Utrecht, and the Austrian Netherlands were all administered by the Head of the House of Habsburg.

- The Pragmatic Sanction, however, did not affect the position of the Holy Roman Emperor because the Imperial crown was elective rather than inherited, even though successive elected Habsburg emperors had led the Holy Roman Empire since 1438.

- Charles VI died in 1740, and his daughter Maria Theresa took his place as Queen of Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Archduchess of Austria, and Duchess of Parma.

- However, she was not a candidate for the title of Holy Roman Emperor, which a woman had never held. Her husband, Francis Stephen, was to be elected Holy Roman Emperor, and she was to inherit the hereditary realms.

- Brandenburg legally remained a part of the Holy Roman Empire, but the Hohenzollerns were fully sovereign rulers of the Prussian Kingdom.

- This placed Frederick as Prussia’s independent monarch but under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor as the ruler of Brandenburg. By the 18th century, the Emperor’s control over the Empire was essentially symbolic.

- The Empire’s numerous provinces behaved as de facto sovereign states and only formally recognised the Emperor’s overlordship over them. As a result, Brandenburg was soon considered a de facto component of the Prussian Kingdom rather than a separate nation.

WAR OF JENKINS’ EAR: 1739 - 1748

- The War of Jenkins’ Ear began as a conflict between Spain and Britain over control of Latin American trade. The first few engagements were all fought in the West Indies and on South America’s northern coast. When the War of the Austrian Succession broke out, Spain and Britain took opposing sides, and the local conflict became entwined with the larger conflict.

- Most of the fighting occurred in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, and significant operations were mostly completed by 1742. The term was invented by British historian Thomas Carlyle in 1858 to refer to Robert Jenkins, commander of the British brig Rebecca, whose ear was supposedly chopped by Spanish coast guards when examining his ship for contraband in April 1731.

BATTLE OF SUMMARY

- Battle of Porto Bello. The Spaniards captured this place on 21 November 1740 by a British fleet of 6 ships under Admiral Vernon. The British loss was trifling.

- Battle of Havana. The battle occurred on 12 October 1748 between a British squadron of seven ships led by Admiral Knowles and a Spanish squadron of the same size. The battle was fought with little zeal, and while the British seized one ship, the outcome was far from decisive. The Spaniards suffered 298 casualties, while the British suffered 179.

- Battle of Carthagena. A British fleet led by Admiral Vernon blockaded this port on 9 March 1741. After a fruitless attack on the forts, Vernon retreated on 9 April, losing 3,000 men throughout the operations.

FIRST CARNATIC WAR

- The First Carnatic War (1740-1748) was the first of wars that established early British authority on the Indian subcontinent’s east coast. The British and French East India Companies fought each other on land to control their respective trading posts in Madras, Pondicherry, and Cuddalore, while French and British naval troops clashed off the coast.

- The French East India Company was nationalised by France in 1720, and proceeded to use it to further its imperial objectives. With Britain’s participation in the War of the Austrian Succession in 1744, this became a subject of contention with the British in India.

- In 1745, a British naval attack on a French fleet prompted French Governor-General Dupleix to request extra forces in India. A navy led by Bertrand-François Mahé, comte de La Bourdonnais arrived in 1746 to assist him. La Bourdonnais led an attack on Madras on 4 September 1746.

- After many days of bombardment, the British surrendered, and the French entered the city. The British leadership was captured and sent to Pondicherry. The town was originally promised to be returned to the British after negotiations, but this was rejected by the Governor-General of French India Joseph François Dupleix, who wanted to annex Madras to French holdings.

- The remaining British prisoners were asked to sign an oath swearing not to fight the French; a few refused, including Robert Clive, who would later become the British Governor of the Bengal Presidency and were kept under weak guard as the French prepared to destroy the fort.

- Clive and three men avoided their unobservant sentinel, snuck out of the fort, and went to Fort St. David.

- Meanwhile, Dupleix had pledged to hand over Fort St. George to the Nawab of Carnatic, Anwaruddin Khan, before the assault but had refused. Anwaruddin replied by dispatching a 10,000-man army to seize the fort from Dupleix. Dupleix, who had lost La Bourdonnais’ support over the position of Madras, had just 930 French men.

- After that, Dupleix began an assault on Fort St. David. After his defeat at Adyar, Anwaruddin Khan, Nawab of the Carnatic, despatched his son Muhammad Ali to help the British defend Cuddalore, and he was vital in repelling a French attack in December 1746. Anwaruddin and Dupleix reached an agreement over the next few months, and the Carnatic troops were removed.

- The French, led by De Brurie, made another assault on Fort St. David, trapping the British troops within the fort’s walls. However, a quick counter-attack by the British and Anwaruddin changed the tide and forced the French to retreat to Pondicherry.

- Major Stringer Lawrence arrived in 1748 to lead the British forces at Fort St. David. With forces arriving from Europe, the British besieged Pondicherry in late 1748.

- The siege was lifted in October 1748 with the coming of the monsoon, and the conflict ended in December with the announcement of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. Madras was returned to British control under its provisions.

FIRST SILESIAN WAR

- The First Silesian War was fought between Prussia and Austria from 1740 to 1742, and it ended in Prussia capturing the majority of Silesia from Austria. The war was fought mostly in Silesia, Moravia, and Bohemia and was part of the larger War of the Austrian Succession.

- After ascending to the throne in May 1740, the newly crowned Hohenzollern King Frederick II of Prussia set his sights on Silesia. Frederick determined that his dynasty’s claims were genuine, and he inherited a powerful and well-trained Prussian army and a wealthy royal treasury from his father, King Frederick William I.

- Austria was in financial difficulties, and its army had yet to be replenished or reformed following its humiliating performance in the Austro-Turkish War of 1737-1739.

- With Britain and France occupied in the War of Jenkins’ Ear and Sweden moving towards war with Russia, the European strategic situation was favourable for an attack on Austria; the Electors of Saxony and Bavaria also had claims against Austria and appeared likely to join in the attack.

- When Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI died without a male successor in October 1740, Prussia had an opportunity to advance its claims. With the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, Charles established his eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, as the heir to his hereditary titles.

- Following his death, she inherited Austria and the Bohemian and Hungarian regions within the Habsburg dynasty. The Pragmatic Sanction was universally recognised by the imperial realms throughout Emperor Charles’ lifetime, but when he died, it was quickly challenged by Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony.

- Several other European nations made similar efforts as Prussia renewed its Silesian claims and prepared for war with Austria. Charles Albert of Bavaria claimed the imperial crown and the Habsburg provinces of Bohemia, Upper Austria, and Tyrol, while Frederick Augustus of Saxony claimed Moravia and Upper Silesia. The Kingdoms of Spain and Naples intended to take Habsburg domains in northern Italy, while France sought control of the Austrian Netherlands, viewing the Habsburgs as historic foes.

- The Electorates of Cologne and the Palatinate joined forces to form the League of Nymphenburg, which sought to weaken or destroy the Habsburg monarchy and its dominant position among German states. The United Kingdom supported Austria and, later, Savoy-Sardinia and the Dutch Republic; the Russian Empire, led by Empress Elizabeth, indirectly aided Austria in the broader struggle by declaring war on Sweden.

Portrait of Maria Theresa - Maria Theresa’s goals in the struggle were twofold: first, to retain her hereditary territories and titles, and second, to secure or compel support for her husband, Duke Francis Stephen of Lorraine, to be elected Holy Roman Emperor, so defending her house’s historic preeminence within Germany.

- Following the death of Emperor Charles on 20 October, Frederick chose to mobilise the Prussian army on 8 November, and gave an ultimatum to Maria Theresa, demanding the cession of Silesia on 11 December.

- The Prussian army had silently massed along the Oder in early December 1740, and on 16 December 1740, Frederick marched his forces across the border into Silesia without a declaration of war.

- The Austrians could only give token opposition and garrison a few fortifications; the Prussians stormed through the region, capturing control of Breslau without a battle on 2 January 1741.

- The fortress of Ohlau was also seized without resistance on 9 January, and the Prussians used it for winter quarters after that.

- By the end of January 1741, nearly all of Silesia was under Prussian control, and the remaining Austrian strongholds of Glogau, Brieg, and Neisse were besieged.

- Following Austria’s inability to defeat the Prussian invasion at Mollwitz, other powers felt encouraged to invade the ailing Kingdom, escalating the conflict into the War of the Austrian Succession.

- In the Treaty of Breslau, France pledged to support Prussia’s annexation of Silesia. In July, it signed the Treaty of Nymphenburg, in which France and Spain agreed to support Bavaria’s territorial claims against Austria.

- Faced with the danger of total partitioning her realm, Maria Theresa spent the months following regrouping and planning a counter-attack. On 25 June, she was formally coronated as Queen of Hungary in Pressburg and began recruiting a new army from her eastern holdings.

- In August, she offered Frederick concessions in the Low Countries and a monetary payment in exchange for Prussia’s evacuation of Silesia, but she was quickly rejected. Seeing Austria’s distress, Frederick began secret peace talks with Neipperg at Breslau despite openly supporting the League of Nymphenburg.

- Despite Prussia’s alliance with France, the prospect of France or Bavaria becoming the dominating power in Germany due to Austria’s destruction did not appeal to Frederick.

- On 9 October, with British encouragement and intervention, Austria and Prussia agreed to a secret truce known as the Klein Schnellendorf Convention, under which both belligerents would suspend hostilities in Silesia.

- Austria would eventually give up Lower Silesia in exchange for a final peace treaty by the end of the year. After a fake siege in early November, Neipperg’s Austrian forces were withdrawn from Silesia to defend Austria against the Western invaders, abandoning Neisse and leaving the entire Silesia under Prussian hands.

- The First Silesian War concluded in a resounding triumph for Prussia, which gained 35,000 square kilometres of new land and a million new subjects, significantly increasing its resources and prestige.

SECOND SILESIAN WAR

- The Second Silesian War, which lasted from 1744 to 1745, established Prussia’s rule over the province of Silesia. The combat occurred mostly in Silesia, Bohemia, and Upper Saxony and was part of the larger War of the Austrian Succession.

- The Treaty of Worms was signed in September 1743 by Austria, Britain-Hanover, and Savoy-Sardinia; Britain had earlier accepted Prussia’s annexation of Silesia as the mediator of the Treaty of Berlin, but this new alliance made no mention of that guarantee.

- The following year, Empress Elizabeth of Russia appointed Alexey Bestuzhev as her chancellor, supporting a pro-British and anti-French agenda that included friendship with Austria and hatred with Prussia. Prussia attempted to improve relations with Russia and gained a limited defensive pact, but Russia constituted an increasing threat to Prussia’s eastern border.

- Battle of Hohenfriedberg. The battle was fought on 3 June 1745 between the Austrians and Saxons led by Charles of Lorraine and the Prussians led by Frederick the Great. The Saxons, who were encamped at Strigau, were assaulted early in the morning and defeated before the Austrians could arrive. After fierce combat, Frederick turned on the Austrians and routed them. The Austrians and Saxons suffered 4,000 casualties, 7,000 prisoners, including four generals, and the loss of 66 guns. The Prussians suffered a loss of 2,000 men.

Carl Röchling depicts a Prussian infantry advance during the Battle of Hohenfriedberg - Battle of Sohr. The battle occurred on 30 September 1745, between 18,000 Prussians led by Frederick the Great and 35,000 Austrians led by Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians attacked the Austrian position, and the Austrians, lacking their usual bravery, made no fight against the steady advance of the Prussian troops and were pushed back in chaos, losing 6,000 killed, wounded, and prisoners, as well as 22 guns. The Prussians suffered between three and four thousand casualties.

- Battle of Hennersdorf. It was fought between 60,000 Prussians led by Frederick the Great and 40,000 Austrians and Saxons led by Prince Charles of Lorraine in November 1745. On the march, Frederick ambushed Prince Charles and defeated his Saxon vanguard, causing massive casualties. As a result, the Austrians were forced to relocate to Bohemia.

JACOBITE RISING OF 1745

- The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an effort by Charles Edward Stuart to restore his father, James Francis Edward Stuart, to the British throne. It occurred during the War of the Austrian Succession, while most of the British Army was fighting on the continent of Europe. It was the final in a series of revolts that began in 1689, with major outbreaks in 1708, 1715, and 1719.

- Charles boarded Du Teillay at Saint-Nazaire in early July, escorted by the Seven Men of Moidart, the most noteworthy of whom was John O’Sullivan, an Irish expatriate and former French officer who served as chief of staff. The two ships set out for the Western Isles on 15 July but were met four days later by HMS Lion, which engaged Elizabeth. Both ships were forced to return to port after a four-hour struggle; losing the Elizabeth and its volunteers and guns was a severe defeat. Charles Edward Stuart landed on Eriskay Island in Scotland on 23 July 1945.

- Many of the people he contacted, notably MacDonald of Sleat and Norman MacLeod, advised him to return to France. They believed that by entering without French military help, Charles had failed to uphold his commitments and were unconvinced by his personal qualities.

- Due to their role in illegally selling tenants into indentured slavery, Sleat and Macleod may have been especially vulnerable to government sanctions.

- Enough were persuaded, although the decision was rarely straightforward; Donald Cameron of Lochiel committed himself only after Charles promised security for the full value of his estate should the rising to prove abortive, while MacLeod and Sleat assisted him in escaping after Culloden.

- 19 August - Rebellion is launched. After determining that he had sufficient military backing, Prince Charles mounted the hill at Glenfinnan while MacMaster of Glenaladale erected his royal standard.

- 17 September - Edinburgh. Although Edinburgh Castle remained in government hands, Charles entered uncontested; James was declared King of Scotland the next day, and Charles was named Regent.

- 21 September - Battle Of Prestonpans. In the face of a Highland charge, Jacobite forces led by Stuart exile Charles Edward Stuart destroyed a government army led by Sir John Cope, whose untrained troops broke. The combat lasted less than thirty minutes and gave Jacobites a major boost in morale, presenting the rebellion as a danger to the British government.

- 15 October - Invasion of England. Murray separated the army into two columns to keep their objective from being discovered by General Wade, the government commander in Newcastle.

- November - Invasion of England. On the 10 November, they arrived in Carlisle, an important border bastion before the 1707 Union but whose defences were now in disrepair, guarded by an army of 80 elderly veterans. Regardless, with siege artillery, the Jacobites would have to starve it into submission, a task for which they needed both the means and the time. After realising that Wade’s relief force would be delayed by snow, the castle surrendered on 15 November.

- 1 December - Turning Point. Many Scots felt they had already gone too far at previous Council sessions in Preston and Manchester. Still, they agreed to continue when Charles informed them that Sir Watkin Williams Wynn would meet them at Derby while the Duke of Beaufort was prepared to conquer the vital port of Bristol. When they arrived in Derby on 4 December, there was no indication of these reinforcements, and the Council met the next day to debate the next moves.

- 18 December - Clifton Moor Skirmish. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, the Clifton Moor Skirmish occurred on the evening of Wednesday, 18 December 1745. Following the decision to withdraw from Derby on 6 December, the fast-moving Jacobite army was divided into three smaller columns; on the morning of 18 December, a small troop of dragoons led by Prince William, Duke of Cumberland and Sir Philip Honywood made contact with the Jacobite rearguard, which Lord George Murray commanded at the time.

- January - Battle Of Falkirk Muir. The Jacobite army besieged Stirling Castle in early January but made little headway, and on 13 January, government soldiers led by Henry Hawley moved north from Edinburgh to liberate it. He arrived in Falkirk on the 15 January, and the Jacobites attacked late in the afternoon of the 17th, catching Hawley off guard.

- February - Cumberland Advances To Aberdeen. Cumberland’s army moved along the coast, allowing it to be resupplied by water, and occupied Aberdeen on 27 February; operations were paused until the weather eased.

- April - Battle Of Culloden. The British won the Battle of Culloden, headed by Cumberland. Against military advice, Charles Edward Stuart engaged in the battle on a flat moor near Inverness. It was a battle between English guns and Scottish daggers and swords.

- April - Prince Charles Disbands The Jacobite Army. A potential 5,000 to 6,000 Jacobites remained in arms, and an estimated 1,500 survivors gathered at Ruthven Barracks over the next two days; however, on 20 April, Charles ordered them to disperse, arguing that French assistance was needed to continue the fight and that they should return home until he returned with additional support.

BATTLES IN 1746 - 1747

- As an opportunistic venture, France entered the conflict between Austria and Prussia. France was the Hapsburg Empire’s most powerful European opponent, fighting Austria in every conflict during the last century. When the French entered on Prussia’s side, Britain, eager to attack France, entered on Austria’s side, along with the Dutch, who also contested land with France. The Hungarians, who had long been subjects of the Austrian Empire, carried the Austrian cause in the early fighting, but in later conflicts, the conflict was largely between France and her Dutch and British allies.

- Battle of Rotto Freddo. Fought in July 1746 when the retreating French army, led by Marshal Maillebois, was attacked by the Austrians, led by Prince Lichtenstein, and was defeated with heavy losses. As a result of this defeat, the French garrison of Placentia, numbering 4,000 men, surrendered to the Imperialists.

- Battle of San Lazaro. It was fought in June 1746 between 40,000 Austrians led by Prince Lichtenstein and French and Spaniards led by Marshal Maillebois. The allies attacked the entrenched Austrian camp and were repulsed after a nine-hour battle with a loss of 10,000 killed and wounded.

- Battle of Negapatam. It was fought off the coast of Coromandel in 1746 between a British fleet of six ships led by Captain Peyton and a French squadron of nine ships led by Labourdonnais. The engagement was virtually entirely at long range. It was indecisive, but after the action, Peyton sheered off and made for Trincomalee, thus admitting defeat even though the French had suffered the greater loss.

- Battle of Cape Finisterre. The battle occurred on 3 May 1747, between a British fleet of 16 sail led by Admiral Anson and a French fleet of 38 sail led by Admiral de la Jonquiere. The French were destroyed totally, losing ten ships and over 3,000 prisoners.

- Battle of Lawfeldt. The battle occurred on 2 July 1747 between the combined Austrians and British, led by the Duke of Cumberland, and the French, led by Marshal Saxe. The village of Lawfeldt was taken and recaptured three times by the French, but about midday, the British centre was driven in, and defeat seemed near when a cavalry charge led by Sir John Ligonier saved the day and allowed the Duke to retire in good order. The Allies suffered 5,620 killed and wounded, while the French lost approximately 10,000.

- Siege of Bergen-op-Zoom. This castle, defended by a garrison of Dutch and English under Cronstrun, was besieged by 25,000 French under Count Lowendahl on 15 July 1747. The besieged launched repeated daring raids, inflicting great losses on the French, but on 17 September, the besiegers completed a lodgment and seized the fortress after fierce combat. During the siege, the French lost 22,000 men and the garrison 4,000. A Scottish brigade in the Dutch army stood out, losing 1,120 men out of a total strength of 1,450.

AFTERMATH OF THE WAR OF AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION

- The eventual diplomatic resolution was part of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of the Austrian Succession and restored the status quo. British territorial and commercial goals in the Caribbean had been thwarted, whereas Spain, unprepared at the start of the war, was able to defend its American colonies successfully.

- Furthermore, the conflict ended British smuggling, and the Spanish fleet was able to send three treasure convoys to Europe during the war, throwing the British squadron at Jamaica off-balance. The Duke of Newcastle’s persistent effort to cultivate Spain as an ally improved relations between Britain and Spain momentarily in succeeding years.

- To avert a repeat of hostilities, Spain nominated a series of Anglophile ministers, including José de Carvajal and Ricardo Wall, who were friendly with British Ambassador Benjamin Keene.

- As a result, Spain remained neutral during the early stages of the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France. However, it later joined the French side and lost Havana and Manila to the British in 1762; while both were regained as part of the peace settlement, the Spanish gave Florida to the British in exchange.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the War of the Austrian Succession?

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) was a conflict triggered by the disputed succession to the Austrian throne after the death of Emperor Charles VI.

- Why did the War of the Austrian Succession start?

The war started because of the death of Emperor Charles VI and the Pragmatic Sanction he had established to ensure the succession of his daughter, Maria Theresa. Many European powers, including Prussia and France, contested the legitimacy of Maria Theresa's rule.

- How did the War of Austrian Succession lead to the Seven Years war?

The War of the Austrian Succession created unresolved conflicts and shifting alliances in Europe. Territorial disputes, colonial tensions, and aggressive expansionist policies persisted after the war. These factors, combined with trigger events like colonial disputes, led to the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756.