British Parliament Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the British Parliament to your students?

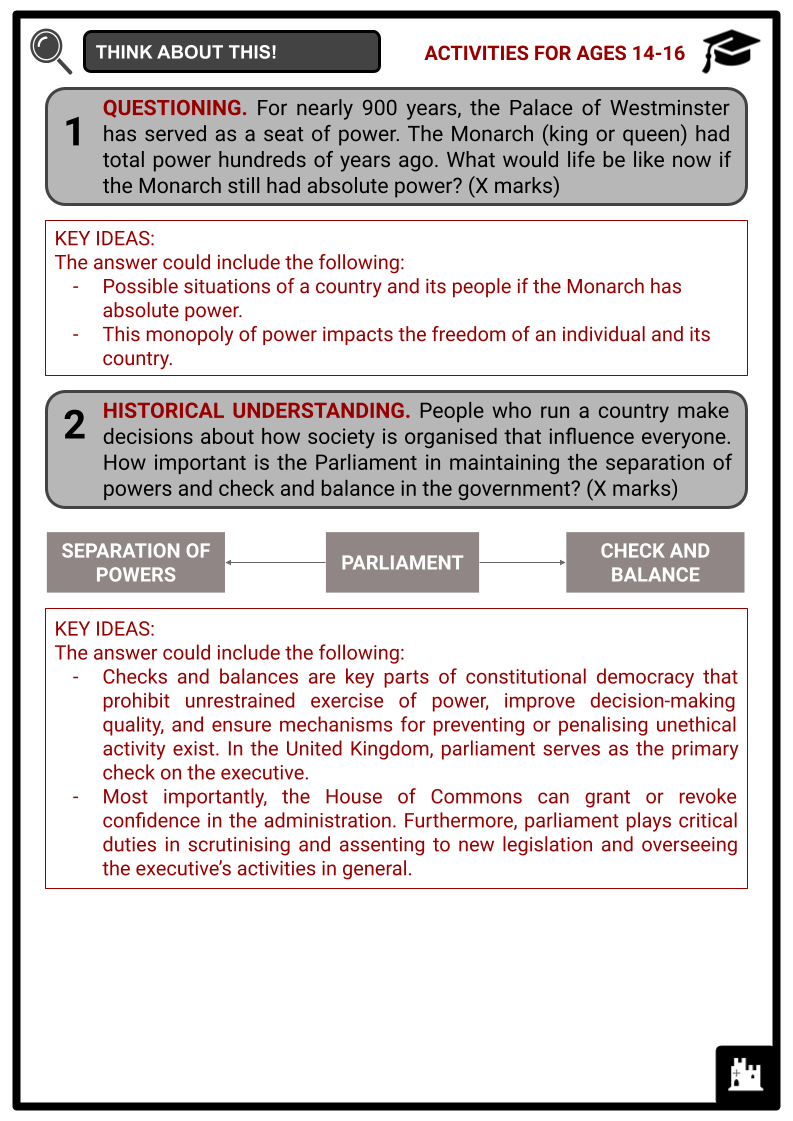

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Historical Background

- Composition Powers

- Legislative Functions and Procedures

- Relationship with the United Kingdom Government

- Petitioning Parliament in the United Kingdom

- Devolution in the United Kingdom Parliament

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the British Parliament!

The legislative branch of the United Kingdom (UK) government is the Parliament. It comprises two different bodies, the House of Commons and the House of Lords, making it a bicameral parliament with two chambers. The House of Commons comprises Members of Parliament (MPs) elected by the people of the UK. On the other hand, members of the House of Lords are not elected. Both houses debate and amend laws until a resolution is reached. Throughout the legislative, each House represents parliament in various committees and councils.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- Following the confirmation of the Treaty of Union by Acts of Union 1707 established in 1215 by the Parliament of Scotland, and the Parliament of England, established in 1235, the Parliament of Great Britain was constituted in 1707.

- Acts of Union adopted by the Parliaments of Ireland and Great Britain expanded Parliament in the nineteenth century. The Acts of Union of 1800 abolished the Irish Parliament and added 100 Irish MPs and 32 Lords to the British Parliament, resulting in the establishment of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Five years after the Irish Free State seceded, the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927 formally altered the name to Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Parliament is divided into two Houses: the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The House of Commons has elected members, while the House of Lords does not.

- Members of the House of Lords are divided into two categories: bishops from the Church of England (Spiritual) and peers (currently appointed titles).

COMPOSITION POWERS

- The legislative authority, the King-in-Parliament, comprises three distinct components: the Monarch, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons. No one person may serve in both Houses, and members of the House of Lords are not allowed to vote in House of Commons elections.

- Previously, no one could be an MP while also holding a profit-making job under the Crown, thus sustaining the separation of powers, but this principle has gradually eroded. MPs appointed to ministerial positions forfeited their seats in the House of Commons and had to run for re-election until 1919 when the practice was repealed. Holders of positions are ineligible to serve as MPs under the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975.

“The first duty of a member of Parliament is to do what they think in their faithful and disinterested judgement is right and necessary for the honour and safety of Great Britain. The second duty is to their constituents, of whom they are the representative but not the delegate. Burke's famous declaration on this subject is well known. It is only in the third place that their duty to party organisation or programme takes rank. All these three loyalties should be observed, but there is no doubt of the order in which they stand under any healthy manifestation of democracy.” - Winston Churchill, Duties of a Member of Parliament, 1954-1955.

- To become law, all Bills must get the Monarch's royal assent, whereas certain delegated laws must be enacted by the Monarch by Order in Council. This legislation is formally made in the king's name by and with the advice and approval of the Privy Council, also known as the King-in-Council in the United Kingdom. Still, the language may differ in other nations. On the other hand, Orders of Council are issued in the name of the Council without the permission of the Sovereign.

- The Crown also has executive powers independent of Parliament, known as prerogative powers, which include the authority to create treaties, declare war, bestow honours, and appoint officers and civil servants.

- In practice, the monarch always exercises these powers on the advice of the Prime Minister and other HM Government ministers. The Prime Minister and his administration are liable to Parliament, which controls public funding, and to the public, which elects legislators.

- The Monarch also picks the Prime Minister, who then appoints both Houses of Parliament members to form a government. This person must command a majority in a confidence vote in the House of Commons. Since the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949, the House of Lords has had far fewer powers than the House of Commons. Except for money bills, the House of Lords debates and votes on all legislation; nevertheless, by voting against a bill, the House of Lords can only delay it for a maximum of two parliamentary sessions a year.

LEGISLATIVE FUNCTIONS AND PROCEDURES

- The basic functions of the parliament are to pass laws, conduct parliamentary scrutiny, and choose ministers. The passage of legislation is arguably the most crucial of these functions. To accomplish this, any new legislation must be thoroughly analysed for laws to be fair. As a result, they must be debated and amended in parliament before becoming law. The billing process is the method by which this is accomplished.

Billing Process for a UK Act of Parliament

- To become an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom, a proposed bill must go through the billing process in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Most bills originate in the House of Commons but can begin in either chamber. The procedure is the same for both Houses:

- First Reading - Read the bill that has been put forward; no debate.

- Second Reading - Debate the bill, but amendments still need to be made.

- Committee Stage - Amendments are made to the bill.

- Report Stage - Changes are reported back to the relevant House.

- Third Reading - Final debates and changes are made.

- Once the House of Commons accepts, the bill is sent to the House of Lords or vice versa for billing. If the bill is changed, it will go through the procedure again.

- If the houses cannot agree on the amendments, they will be passed back and forth between the Houses of Commons and Lords until they do.

- Finally, once both houses have agreed, the bill is transmitted to the Crown for royal assent.

- This is the final stage of the billing procedure, in which the monarch signs the bill into law.

- Another parliament responsibility is providing ministers to represent and serve in cabinet as part of the government's executive branch. A minister must be a member of one of the Houses of Parliament.

- Finally, people's representation is a function of the UK parliament; however, this occurs only through the House of Commons, the elected chamber of parliament.

- The Speaker of the House of Commons and the Lord Speaker of the House of Lords preside over both houses of the British Parliament. The consent of the Sovereign is required for the Commons before the election of the Speaker becomes legal, but it is always granted by modern tradition.

- Before July 2006, the Lord Chancellor presided over the House of Lords, but his authority as Speaker was limited. However, as part of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, the Speaker of the House of Lords was split from the office of Lord Chancellor, albeit the Lords continue to be largely self-governing.

- The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 establishes a Supreme Court of the United Kingdom to take over the Law Lords’ previous appellate jurisdiction as well as some powers of the Privy Council’s Judicial Committee, and it abolishes the Lord Chancellor’s functions as Speaker of the House of Lords and Head of the Judiciary of England and Wales.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE UNITED KINGDOM GOVERNMENT

- The House of Commons holds the British government accountable. The House of Commons, however, does not elect the Prime Minister or members of the Government. Instead, the Crown asks the person most likely to command the support of a majority in the House to form a government, usually the leader of the largest party in the House of Commons. By convention, the Prime Minister and most Cabinet members are House of Commons members to be answerable to the Lower House.

- Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home, who became Prime Minister in 1963, was the last Prime Minister to be a member of the House of Lords. To comply with the norm that held him accountable to the Lower House, he renounced his peerage and was elected to the House of Commons within days of becoming Prime Minister. Governments tend to dominate Parliament’s legislative powers by utilising their built-in majority in the House of Commons and patronage authority to install sympathetic peers in the Lords.

- Parliament exerts control over the executive by passing or rejecting its Bills and forcing Crown Ministers to account for their actions, either at Question Time, a constitutional convention in the United Kingdom that meets every Wednesday at noon when the House of Commons is in session, during which the prime minister addresses questions from MPs. In this instance, Ministers are asked questions by members of their respective Houses and must respond.

- The House of Lords can scrutinise the executive through Question Time and its committees but cannot bring the Government down. A ministry must always maintain the House of Commons’ trust and support.

- The Lower House might show disapproval by rejecting a Motion of Confidence or passing a Motion of No Confidence. The Government normally introduces Confidence Motions to strengthen its support in the House, whilst the Opposition does not.

- Many votes are deemed votes of confidence despite the language given above. Important bills on the Government’s agenda are often seen as matters of confidence.

- The failure of such a bill in the House of Commons implies that a government no longer trusts the House. The same impact is obtained if the House of Commons withdraws Supply, that is, if the budget is rejected.

- When a government loses the confidence of the House of Commons, that is, when it loses the ability to secure the basic requirement of the House of Commons’ authority to tax and spend Government money, the Prime Minister must resign or seek the dissolution of Parliament and a new general election.

- Otherwise, the government’s machinery will come to a halt within days. The third option, mounting a coup or an anti-democratic revolution, is unlikely to be considered today.

- Even though all three scenarios have occurred in recent years, even in sophisticated economies, international relations have prevented a disaster.

PETITIONING PARLIAMENT IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

- One of the civil rights in the United Kingdom is the right of every individual to petition their parliament on subjects of concern. If a petition receives sufficient signatures, it may urge Parliament to debate specific concerns. Petitioning is an excellent way for parliament to learn about and respond to public concerns. The power to petition Parliament is one way for the public to impact Parliament directly.

- A UK Parliament petitions website organises petitions in the UK. If a petition receives 10,000 signatures, the government is required to respond. If it receives 100,000 signatures, a debate in parliament is normally held. The House of Commons Petitions Committee is in charge of coordinating this.

A successful example is a 2015 petition arguing that the government should welcome more refugees and provide more assistance to refugees. Over 450,000 people signed the petition. Following this, the government accepted 20,000 more Syrian refugees through the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Relocation scheme and spent an additional £100 million on humanitarian aid.

DEVOLUTION IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PARLIAMENT

- Devolution is a fundamental component of the parliamentary system of the United Kingdom. It is a crucial element for the United Kingdom because parliament, the government, and the judiciary share devolved powers with Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and England. These powers are typically over more local issues such as education and the environment, although they vary depending on who receives them.

- Even though the parliament has delegated some powers to regional and local governments, there are other powers that only the United Kingdom parliament has; these are known as reserved powers.

- They include criminal law, human rights, international and national trade rules, National Health Service legislation, and detention powers. There are several reasons why parliament has delegated some of its powers to regional and local governments.

- The parliament shared devolved powers because some of these areas, particularly Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, wanted greater sovereignty over their country.

- Scotland and Wales held successful referendums in 1997 to determine if they wanted autonomous powers. On the other hand, Northern Ireland obtained devolved powers as part of the Belfast Agreement 1998, also known as the Good Friday Agreement 1998, which helped resolve the conflict between Ireland and the United Kingdom.

- Giving devolved powers to these nations inside the UK was, therefore, motivated by their desire for autonomy and independence from the central government. The final reason parliament shared devolved powers was to reduce the load on the system, particularly for the devolution of parliamentary functions within England.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the British Parliament?

The British Parliament is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, consisting of two houses: the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

- How is the Prime Minister elected?

The Prime Minister is usually the leader of the political party that wins the most seats in the House of Commons during a general election.

- How often are general elections held?

General elections are held at least every five years. However, the Prime Minister can call for an earlier election with the approval of the House of Commons.