First Sino-Japanese War Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the First Sino-Japanese War to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Historical Background

- Kim Ok-Gyun Affair and Donghak Rebellion

- War

- End of War

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the First Sino-Japanese War!

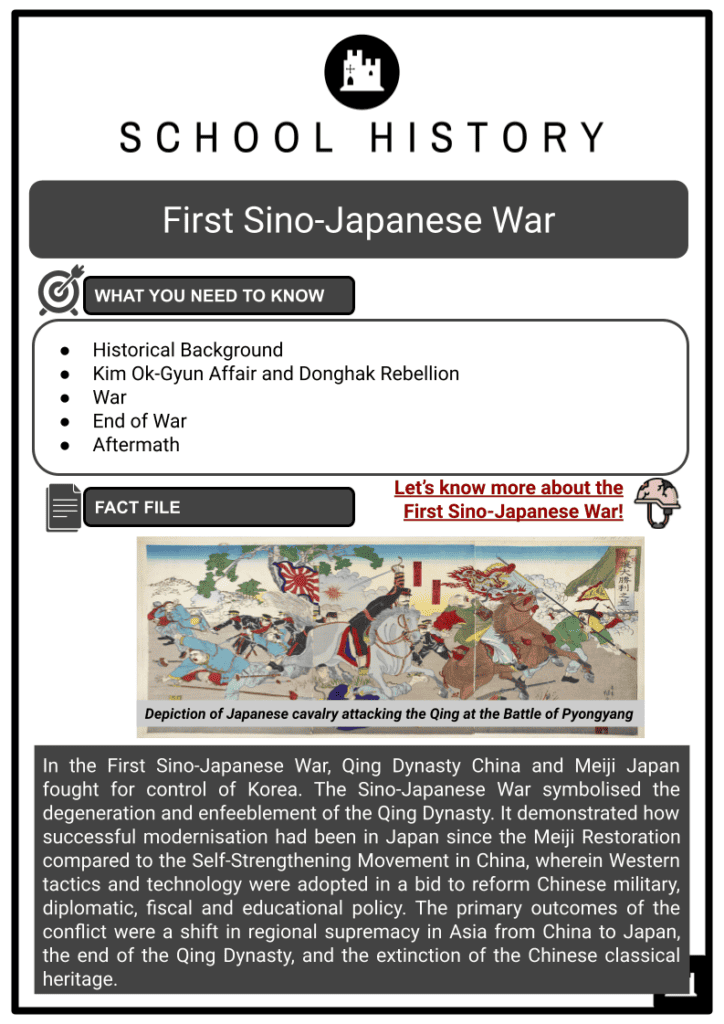

In the First Sino-Japanese War, Qing Dynasty China and Meiji Japan fought for control of Korea. The Sino-Japanese War symbolised the degeneration and enfeeblement of the Qing Dynasty. It demonstrated how successful modernisation had been in Japan since the Meiji Restoration compared to the Self-Strengthening Movement in China, wherein Western tactics and technology were adopted in a bid to reform Chinese military, diplomatic, fiscal and educational policy. The primary outcomes of the conflict were a shift in regional supremacy in Asia from China to Japan, the end of the Qing Dynasty, and the extinction of the Chinese classical heritage.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- After two centuries, the shoguns or the military dictators of the Edo period’s policy of seclusion in Japan came to an end when the nation was opened up to trade by the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. The Convention led to the signing of a treaty between the United States (US) and the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan. The newly established Meiji administration began reforms to centralise and modernise Japan in the years after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the end of the shogunate. Intending to bring Japan up to par with the Western powers, the Japanese had despatched delegates and students from all over the world to study and incorporate Western arts and sciences.

- Japan underwent these reforms to change from a feudal society to a contemporary industrial state. The Qing Dynasty of China began reforming its military and political ideology at about the same time, though it had far less success.

KOREAN POLITICS

- King Cheoljong passed away without leaving a male heir in January 1864. As a result of Korean succession laws, King Gojong, who was 12 years old at the time, took the throne. King Gojong was too young to reign, so his father, Yi Ha-ng, took over as regent and became the Daewongun, or ruler of the grand court. He ruled Korea in his son’s name.

- The Daewongun started a series of changes with his rise to power meant to benefit the monarchy at the expense of the Yangban class.

King Gojong - Because the King’s in-laws were historically influential in Korea, the Daewongun recognised that any future daughters-in-law might challenge his rule. He therefore made an effort to neutralise any potential challenge to his authority by choosing an orphaned girl from the weakly political Yeoheung Min clan to be the new Queen for his son.

- The Daewongun was comfortable in his position of authority because Queen Min was his daughter-in-law and the royal consort. However, once she was crowned Queen, Min gathered all her relations and assigned them to powerful positions in the King’s name. The Queen also formed alliances with the Daewongun’s political adversaries, and by the end of 1873, she had amassed sufficient authority to depose him.

- 1876. The Ganghwa Treaty was signed on 26 February 1876, opening Korea to Japanese trade following clashes between the Japanese and Koreans.

- 1880. Kim Hong-jip, a Korean politician, led an expedition that the King despatched to Japan in 1880 as an eager observer of the improvements.

- 1882. King Gojong broke with convention and sought Chinese guidance before establishing diplomatic relations with the US. On 22 May 1882, the Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation was formally signed between Korea and the US in Incheon, following discussions mediated by the Chinese in Tianjin.

- 1883. In 1883, Korea inked trade and commerce agreements with Germany and Great Britain.

- 1884. Agreements between Italy, Russia and Korea were made in 1884.

- 1886. Korea inked trade and commerce agreements with France in 1886.

IMO INCIDENT

- The Imo Incident, also known as the Imo Mutiny, or Jingo-gunran in Japanese, was a violent revolt and riot in Seoul that began on 23 July 1882 by soldiers of the Joseon Army, who disgruntled members of the larger Korean population eventually joined.

- The insurrection erupted partly due to King Gojong’s support for reform and modernisation, as well as the use of Japanese military advisers.

- The rebellion was sparked partly by a reaction to unpaid military wages and the discovery of sand and poor rice in soldiers’ rations. Soldiers could be paid with rice because it was used as currency. Rioters killed many government officials, burnt the mansions of high-ranking government officials and occupied Seoul’s Changdeokgung Park.

- They also turned on members of the Japanese legation in the city, who managed to flee on the British ship HMS Flying Fish. Several Japanese were slain during the day of unrest, including military adviser Horimoto Reizo. Rioters also stormed Min Gyeom-ho’s residence, lynched Lord Heungin, Yi Choe-eung, and attempted to slay Queen Min, even reaching the Royal Palace.

- The poor people of Seoul from Wangsim-li and Itaewon joined the commotion, and Queen Min escaped to another residence by disguising herself as a court lady.

Contemporary woodblock print depicting the attack on the Japanese legation in Seoul - Some attribute the outbreak of violence to aggressive policies and behaviour of Japanese military advisers who had been training the new and first modernised military force of Korea, known as the Special Skills Force, since 1881.

RE-ASSERTION OF CHINESE INFLUENCE

- Early reform efforts in Korea were severely hampered following the Imo Incident. Following the episode, the Chinese reasserted their dominance on the peninsula and began intervening directly in Korean internal matters. After stationing forces at critical places in Seoul, the Chinese launched several actions to exert significant influence over the Korean government.

- The officials of the Qing government sent two foreign affairs special advisers to Korea to advocate Chinese interests: the Chinese diplomat Ma Jianzhong and the German Paul Georg von Möllendorff, a close confidant of Li Hongzhang, a Chinese statesman and diplomat of the Qing Dynasty. A team of Chinese officials also took over the army’s training, supplying the Koreans with 1,000 weapons, 2 cannons and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

- China and Korea signed a contract stating that Korea depended on China, granting Chinese merchants the freedom to conduct overland and marine trade within its borders freely. It also offered the Chinese an advantage over the Japanese and Westerners, giving them unilateral extraterritoriality privileges in civil and criminal actions. The treaty boosted the number of Chinese merchants and dealers, seriously damaging Korean merchants.

- Although it allowed Koreans to trade reciprocally in Beijing, the arrangement was not a treaty and was instead established as a vassal ordinance. Furthermore, the Chinese oversaw the establishment of a Korean Maritime Customs Service, led by Möllendorff, the following year. Korea was reduced to a Chinese semi-colonial tribute state, with King Gojong unable to appoint diplomats without Chinese consent and troops stationed in the country to protect Chinese interests.

OTHER INCIDENTS THAT TOOK PLACE BEFORE THE FIRST SINO-JAPANESE WAR

- The Min clan’s factional strife and ascent. In Korea during the 1880s, two competing factions arose. One was a tiny group of reformers centred on the Gaehwadang (Enlightenment Party), who were dissatisfied with the narrow scope and arbitrary speed of reforms. The other one was the Sadaedang, a group of Min clan.

- Gapsin Coup. Members of the Gaehwadang had yet to obtain nominations to important government positions in the two years preceding the Imo incident, preventing them from carrying out their reform plans. As a result, they were willing to gain power by whatever means necessary.

- Nagasaki incident. The Nagasaki event occurred in 1886 in the Japanese port city of Nagasaki. Four vessels from the Qing Empire’s navy, the Beiyang Fleet, reportedly halted in Nagasaki for maintenance. Some Chinese seamen sparked the disturbance by causing havoc in the city.

KIM OK-GYUN AFFAIR AND DONGHAK REBELLION

- Kim Ok-gyun, a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary, was killed in Shanghai on 28 March 1894. Kim went to Japan after his involvement in the 1884 coup, and the Japanese refused to extradite him. Many Japanese activists considered him to be able to play a role in the modernisation of Korea. Nevertheless, Meiji government leaders were more hesitant. They deported him to the Bonin Islands after some objections. After some deliberation, British officials in Shanghai concluded that the restrictions prohibiting extradition did not apply to a corpse and handed over his body to Chinese authorities.

- The Japanese government took that as an unacceptable insult in Tokyo. Li Hongzhang viewed Kim Ok-gyun’s violent murder as a betrayal and a loss for Japan’s stature and dignity. The Chinese authorities decided not to charge the assassin. Nonetheless, he was permitted to accompany Kim’s mangled body back to Korea, where he was lavished with awards and medals.

- Kim’s assassination had also questioned Japan’s commitment to its Korean supporters. Earlier that year, authorities in Tokyo prevented an attempt to assassinate Pak Yung-hio, another Korean commander of the 1884 rebellion. Two accused Korean assassins were granted sanctuary at the Korean legation, which sparked a diplomatic uproar.

- Tensions between China and Japan were high, but war was not yet inevitable, and Japan’s outrage over Kim’s assassination began to fade. However, the Donghak Rebellion started in Korea in late April. Peasants in Korea rose in open revolt against the Joseon government’s excessive taxation and poor financial management. The revolution was the largest in Korean history. However, on 1 June, speculations that the Chinese and Japanese were about to send troops reached the Donghaks, and the rebels agreed to a truce to remove any grounds for foreign intervention.

- 2 JUNE. Japan’s cabinet voted to send soldiers to Korea. As a result of the problematic situation on the Korean Peninsula, the Chinese had taken steps in May to prepare for the mobilisation of their troops in the provinces of Shandong, Zhili and Manchuria.

- 3 JUNE. King Gojong requested Chinese government assistance in crushing the Donghak Rebellion at the urging of the Min clan and the behest of Yuan Shikai.

- 9 JUNE. The troops bound for Korea boarded three British-owned steamers chartered by the Chinese government and arrived in Asan on 9 June.

- 25 JUNE. On 25 June, 400 additional troops came. As a result, at the end of June, Chinese General Ye Zhichao commanded approximately 2,800–2,900 soldiers at Asan.

- 27 JUNE. Simultaneously, on 27 June, a reinforced brigade of around 8,000 men (the Oshima Composite Brigade) led by General Shima Yoshimasa was dispatched to Chemulpo.

WAR

- By July 1894, Chinese soldiers in Korea numbered 3,000–3,500, far outnumbering Japanese forces. They could only be supplied from the sea via Asan Bay. The Japanese intended to blockade the Chinese at Asan before encircling them with ground forces. The first plan of Japan was to establish control of the sea, which was crucial to its activities in Korea. The ability to command the sea would allow Japan to send troops to the mainland. Japan’s Fifth Division would land at Chemulpo on Korea’s western coast to engage and push Chinese soldiers northwest up the peninsula and pull the Beiyang Fleet into the Yellow Sea for a final confrontation.

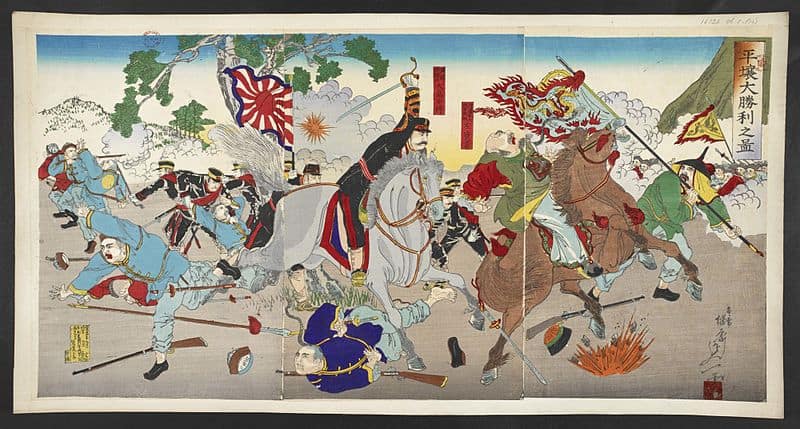

BATTLE OF PUNGDO

- The first naval combat of the First Sino-Japanese War was the combat of Pungdo. It took place on 25 July 1894, off the coast of Asan, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea, between Imperial Japanese Navy cruisers and Chinese Beiyang Fleet components.

- Both countries had already sent troops to Korea in response to requests from various groups inside the Korean government. In early July, Chinese forces from the Huai Army were stationed in Asan, south of Seoul, and could only be efficiently supplied by sea through the Bay of Asan.

- The Japanese strategy was to obstruct the Bay of Asan’s entrance while ground forces pushed overland to envelop the Chinese detachment in Asan before reinforcements arrived by sea.

Naval Battle near Phungdo in Korea (Chôsen Hôtô kaisen no zu) in the First Sino-Japanese War

CONFLICT IN KOREA

- On 25 July, Major-General Shima Yoshimasa led a mixed brigade of about 4,000 troops on a rapid forced march from Seoul south towards Asan Bay to face Chinese troops garrisoned at Seonghwan Station east of Asan and Kongju, commissioned by the new pro-Japanese Korean government.

- The Chinese forces stationed near Seonghwan were led by General Ye Zhichao and totalled approximately 3,880 men. They had fortified their position in anticipation of the approaching Japanese by digging trenches, building earthworks, including six redoubts protected by abatis, and flooding adjacent rice fields. However, planned Chinese reinforcements were lost on the British-chartered vessel Kowshing.

- The two forces met in the morning of 27–28 July 1894, just outside Asan, in an encounter that lasted till the following day. The fight began with a diversionary attack by Japanese troops, which was immediately followed by the main assault, which quickly outflanked the Chinese defences.

- When the Chinese troops realised they were being outflanked, they abandoned their defensive positions and fled toward Asan. The Chinese progressively lost ground against the more significant Japanese numbers, eventually breaking and running towards Pyongyang, leaving arms, ammunition and all artillery.

DECLARATION OF WAR

- China and Japan declared war on one other on 1 August 1894. The rationale, phrasing and tone used by both nations’ governments in their declarations of war were noticeably different. The tone of the Japanese proclamation of war declared in the name of the Meiji Emperor appears to have had one eye on the greater international community, with terms like ‘Family of Nations’, ‘Law of Nations’, and references to international treaties. This starkly contrasted to the Chinese approach to foreign affairs, which was historically characterised by a refusal to treat other nations on an equal diplomatic basis and instead insisted on such foreign authorities paying tribute to the Chinese Emperor as vassals.

- By 4 August, the remaining Chinese soldiers in Korea had withdrawn to the northern city of Pyongyang, where Chinese troops welcomed them. The city’s 13,000–15,000 defenders undertook defensive repairs to slow the Japanese assault.

- On 15 September, the Imperial Japanese Army converged on Pyongyang from several directions. The Japanese attacked the city and eventually overcame the Chinese with a rear attack; the defenders surrendered. The remaining Chinese troops fled Pyongyang and went northeast towards the seaside town of Uiju, taking advantage of heavy rain overnight. The entire Japanese force invaded Pyongyang early on 16 September.

- The Japanese triumph in Pyongyang had succeeded in driving Chinese troops north to the Yalu River, effectively eliminating all Chinese armed forces on the Korean Peninsula. Admiral Ding acquired a message from Pyongyang alerting him of the defeat shortly before the convoy’s departure. As a result, the troops’ redeployment near the mouth of the Taedong River became unnecessary.

- Following their defeat in Pyongyang, the Chinese withdrew from northern Korea and assumed defensive positions in fortifications along the Yalu River near Jiuliancheng. After gaining reinforcements on 10 October, the Japanese moved quickly north towards Manchuria.

- General Nozu Michitsura’s 5th Provincial Division advanced towards Mukden (present-day Shenyang), while Lieutenant-General Katsura Tar’s 3rd Provincial Division pursued retreating Chinese forces west towards the Liaodong Peninsula.

- The 3rd Provincial Division had taken Tatungkau, Takushan, Xiuyan, Tomucheng, Haicheng and Kangwaseh by December. During a harsh Manchurian winter, the 5th Provincial Division marched towards Mukden.

- The Japanese 2nd Army Corps, led by Yama Iwao, arrived on the south shore of the Liaodong Peninsula on 24 October and pushed fast to seize Jinzhou and Dalian Bay on 6–7 November. The Japanese besieged Lüshunkou (Port Arthur), a strategic harbour.

Fall of Lüshunkou

- By 21 November 1894, the Japanese had seized the city of Lüshunkou, commonly known as Port Arthur, with little resistance and few losses. Japanese forces proceeded with the uncontrolled murdering of people during the Port Arthur Massacre, with unsubstantiated figures in the thousands, after encountering a display of the disfigured remains of Japanese soldiers as they entered the town. This occurrence was widely regarded with scepticism since the world was still in disbelief that the Japanese were capable of such actions – it appeared more likely to have been the exaggerated propagandist move of a Chinese government to undermine Japanese hegemony.

Fall of Weihaiwei

- Following that, the Chinese fleet fled behind the Weihaiwei defences. However, it was later surprised by Japanese land forces, who coordinated with the navy to outflank the harbour’s defences. The siege of Weihaiwei lasted 23 days, with the critical land and naval confrontations occurring between 20 January and 12 February 1895. Historian Jonathan Spence said, “the Chinese admiral retired his fleet behind a protective curtain of contact mines and took no further part in the fighting.” The Japanese commander marched his troops over the Shandong peninsula and into Weihaiwei, where the Japanese ultimately overpowered the siege.

END OF WAR

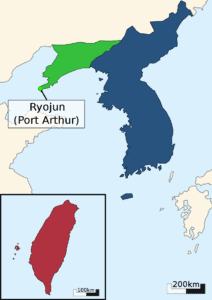

- On 17 April 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed. The treaty stated that China recognised Korea’s total independence and ceded the Liaodong Peninsula, Penghu Islands and Taiwan to Japan in perpetuity. The disputed islands, the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, were not named in the treaty, but Japan annexed them to Okinawa Prefecture in 1895.

- In addition, as war reparations, China was to pay Japan 200 million taels in silver. The Qing administration also negotiated a commercial treaty allowing Japanese ships to operate on the Yangtze River, manufacturing factories to operate in treaty ports and opening four more ports to international trade.

- However, Russia, Germany and France conducted the Triple Intervention in days, forcing Japan to give up the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for another 30 million taels of silver (about 450 million yen).

- The Qing government of China paid 200 million Kuping taels, or 311,072,865 JPY, after the war, making the war a net profit for Japan, given their war fund was just 250,000,000 yen.

Blue: Japanese sphere of influence Red: Annexed by Japan Green: Annexed by Japan, but temporarily lost due to the Triple Intervention; Kwantung Leased Territory (Ryojun) was later re-annexed after the Russo-Japanese War - Several Qing officials in Taiwan determined to resist Japan’s cession of Taiwan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and on 23 May, the island declared itself an independent Republic of Formosa. On 29 May, Japanese soldiers led by Admiral Motonori Kabayama invaded northern Taiwan, defeating Republican forces and occupying the island’s key towns in a five-month war. The escape of Liu Yongfu, the second Republican president, and the surrender of the Republican capital Tainan essentially ended the campaign on 21 October 1895.

AFTERMATH

- The Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War resulted from two decades of modernisation and industrialisation. The adoption of a Western-style military meant that the conflict revealed the superiority of Japanese tactics and training. The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Imperial Japanese Army inflicted a run of defeats on the Chinese through foresight, endurance, strategy and organisational might. Japan’s international standing rose due to the victory and mirrored the Meiji Restoration’s success.

- Japan incurred a minor loss of life and treasure in exchange for Chinese domination over Taiwan, the Pescadores and the Liaotung Peninsula. Its decision to renounce its isolationist policies and learn sophisticated policies from Western countries became a model for other Asian governments to emulate. As a result of the war, Japan gained equal standing with the Western countries, and its triumph placed Japan as the dominating force in Asia, providing them with various critical resources, such as iron, for modernisation and development.

- For China, the war exposed much corruption in the Qing administration’s government and policies. Although the Qing Dynasty had invested considerably in modern ships for the Beiyang Fleet, the Qing’s institutional inadequacy prevented the creation of effective naval strength. Japan has traditionally been regarded as a subordinate part of the Chinese cultural realm. European countries had defeated China in the 19th century, but defeat by an Asian nation was a crushing incident.

- Japan had accomplished its goal of ending Chinese power in Korea but was compelled to give up Port Arthur in exchange for more extensive financial indemnity. The European nations, particularly Russia, had no objections to the treaty’s other articles but believed Japan should not obtain Port Arthur because they had their own goals in that part of the world.

- Russia encouraged Germany and France to join in putting diplomatic pressure on Japan, resulting in the Triple Intervention of 23 April 1895.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:16126.d.1(14)-The_Battle_of_Pyongyang.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gojong_of_the_Korean_Empire_02.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Imogullan1.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_Phungdo.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Shimonoseki

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the First Sino-Japanese War?

The First Sino-Japanese War fought between 1894 and 1895, was a conflict between the Qing Dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan over influence and control in Korea and Taiwan.

- Who won the First Sino-Japanese War?

Japan emerged as the victor in the war. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed in 1895, officially ended the conflict and resulted in China ceding Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands to Japan, recognising Korean independence, and granting territorial and economic concessions to Japan.

- Why did Japan invade China?

Japan invaded China primarily due to its expansionist ambitions, resource shortages, and political instability in China. Japan sought to secure territories like Manchuria for resources, establish regional dominance, and address domestic economic needs. Incidents like the Mukden Incident provided pretexts, while nationalism, strategic considerations, and deteriorating relations with Western powers further fueled the conflict.