Blackamoors Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Blackamoors to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Black presence in Tudor England

- Lives and legal status of blackamoors in England

- Late Elizabethan rule and early Stuart period

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Blackamoors!

Historians have found that numerous people of African origin lived in England not only during the Roman occupation of Britain and the medieval period, but also during the Tudor rule. Africans were described by English people in numerous archival sources as blackamoors. Blackamoors took a variety of jobs, lived in cities and rural areas and integrated into English society. They were paid wages and considered free members of the community. The Stuart period marked a shift in the status of Africans in England, as English participation in the slave trade intensified.

Black presence in Tudor England

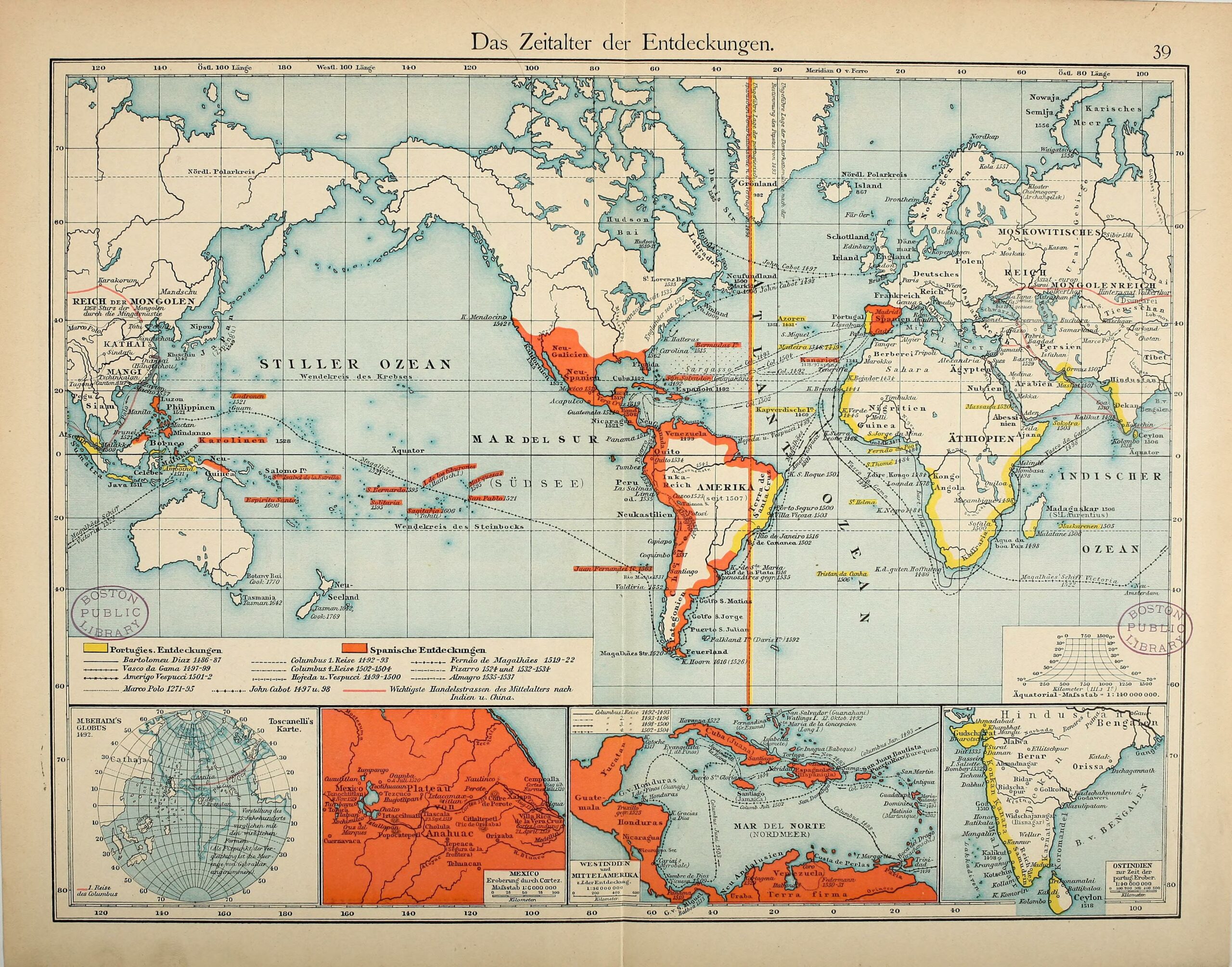

- Historians are finding more proof that people of African origin lived in England during the medieval period. It appears that these numbers were considerably smaller than from the Roman occupation of Britain, during which Africans had travelled to and were highly likely to have settled in England. A wealth of evidence including letters, legal records and church records of births and deaths has also been discovered by historians, such as Onyeka Nubia, Miranda Kaufmann and Imtiaz Habeeb, revealing that numerous people of African origin lived in England during the Tudor period (1485–1603).

- England was not the first country in Europe to see a growth in its Black population during the early modern period (c1450–1800).

- In fact, in the early 15th century, a significant Black population evolved across southern Europe, notably in Portugal, Spain and Italy.

- This was because it was the Portuguese that first began to settle in the African territories and islands during this period.

- On the other hand, the more northerly countries of the continent, such as France and the Netherlands, saw smaller numbers.

- As a consequence, there emerged an increased contact between Africans and Europeans.

- Meanwhile, in Tudor England, the number of people of African origin or descent was estimated to be in the hundreds.

- These people are often called the Black Tudors and were mentioned in historic records as blackamoors.

- The term ‘blackamoor’ first appeared in the St Aldermanbury parish register in 1565 to describe a man named ‘Jhon’.

- Over the succeeding century, blackamoor and its variants became the most widely used term by the English to describe both African men and women, as it lacked a feminine form.

- The blackamoors in the first half of the 16th century mostly arrived via Spain or Portugal.

- Others came to England through English trade with Africa.

How did the Black Tudors come to England?

- Some came directly from Africa as traders or as ambassadors.

- Others arrived with the entourages of royals.

- Several travelled with merchants and aristocrats, especially when the English started to trade with Morocco and West Africa directly from the 1550s.

- Many came as the consequence of English privateering and raids on the Spanish empire.

What were the archival sources that revealed the Black presence in England?

Parish registers

- Parish registers provided the most evidence of Black presence in England, thanks to the government’s directive in the early 16th century that parish churches keep detailed records of the baptisms, marriages and burials that they performed.

- Despite this, the information recorded in the registers was only limited to name, dates and ethnicity.

- Parish registers from 1558 until the 17th century listed Africans, which, aside from blackamoors, were described as ‘Neygers’, ‘Aethiopians’ and ‘Negroes’.

- The search for evidence of Black presence was difficult in these sources because parish registers are kept in scattered local record offices and are rarely indexed.

Tax returns

- The Tudor government taxed foreigners twice as much English people. However, the alien poll tax appeared to have not been universally imposed on Africans, probably due to the small amount of revenue involved.

- While tax returns seldom recorded the names of blackamoors, they could be relied on to mention some details of their masters.

Household accounts

- Blackamoors were often recorded when they were employed in royal, noble or gentry households.

- They appeared in the lists of members of a household or in payments for clothing, shoes, travel and other essentials. This offers some material details of Black lives during the period.

Church and municipal accounts

- The accounts of parishes and civic authorities also referenced Africans. These give brief details about how Africans were treated in local societies.

Court records

- Quarter Sessions identified Africans in cases of petty crimes and issues of administrative law.

- Royal court records, including those of the Court of Chancery, the Court of Star Chamber, the Court of Requests and the High Court of Admiralty, also mentioned blackamoors.

Church court records

- Church court records referenced Africans, who were at times charged with involvement in moral offences such as fornication and prostitution.

Wills and inventories

- Only a few wills mentioned Africans, offering some insight into their standing in the household.

- Additionally, an inventory of the property of an African woman, Cattelena of Almondsbury, was found in Bristol. This reveals that a blackamoor was allowed to hold property in early modern England.

Diaries and letters

- Diaries of the period had very limited references to Africans, while letters found in the state papers mentioned Africans a few times.

These archival sources cited numerous terms to describe people of African origin, hence it proved difficult to identify them. Other sources of evidence of Black presence in England include English voyage accounts to Africa and the Caribbean, as well as literary and visual materials of the time that should be treated with caution.

Lives and legal status of blackamoors in England

- Numerous sources uncovered that Africans came to England in different ways and, once in England, they took a variety of jobs and resided in different locations in the country.

Jobs taken by blackamoors

-

- Many served in the households of the monarch, gentlemen and merchants.

- Some were employed as carpenters and skilled craftspeople.

- Some can be found working as sailors and divers.

- Very few resorted to prostitution and crime to survive.

- They had a trade, such as needle makers and silk weavers.

- They worked as cooks, laundresses, stable hands and musicians.

- Some Africans were recorded as having no master at all, and were in fact paid wages and compensated in kind or with occasional rewards, as was normal practice during the period.

- Meanwhile, evidence shows how blackamoors adhered to Christianity and how they interacted with English society.

- Parish registers revealed that they were baptised, married to English people and buried in parish graveyards across the country, in both cities and the more rural areas. This indicates a level of acceptance and integration.

- Blackamoors were deemed suitable converts to Christianity, hence were properly taught in the faith. It was also ensured that they had a genuine desire to convert before they were baptised.

- They married English people and other Africans, demonstrating a further internalising of the Christian religion.

- They were buried using the ceremony that was adopted by the rest of the English population.

- Those who behaved outside the bounds of what was expected of them in the Christian society faced the same consequences as other offenders. This is also an indication of the integration of blackamoors into early modern society.

- While there were some cases where Africans might have retained the beliefs they had grown up with or might have been exposed to religions other than that of the Church of England, these were not commonly recorded or admitted to in public.

What was the legal status of blackamoors?

-

- Africans were allowed to be baptised.

- Some were left inheritances in wills.

- They could marry and testify in court.

- They were paid wages and some were entirely independent.

- Evidence indicates that many blackamoors were free members of society, contrary to the general view that all Africans were enslaved by the English. The reason for many Africans’ legal status was that England did not participate in the slave trade until the first half of the 17th century. In fact, during Tudor times, there was no legislation that explicitly forbade slavery in England, but neither was there a law that permitted it.

Late Elizabethan rule and early Stuart period

- Elizabeth I, the last Tudor monarch, reigned from 1558 to 1603. While England would not be involved in the slave trade until later, the first slaving voyages led by privateers such as Francis Drake and Jon Hawkins were supported by the queen. Such privateers were known to seize Spanish cargoes of enslaved people and other loot like gold and spices for resale, as they recognised that trafficking people could be lucrative and improve one’s standing.

- As a result of these activities by merchants, explorers and privateers, the population of blackamoors in England rose considerably during the period.

- While most of them resided in and around the port cities, they were also found in the more rural areas, such as Cornwall, Devon, Cambridgeshire, Gloucestershire, Dorset, Kent, Northamptonshire, Somerset, Suffolk and Wiltshire.

- Additionally, African servants were employed more and more in the households of the nobility.

- In 1596, the privy council of Elizabeth I authorised a merchant of Lubeck named Caspar Van Senden to transport blackamoors from England into Spain and Portugal. This, however, required the consent of their masters.

- Van Senden soon saw that the privy council warrant was ineffective, as the merchants and members of the nobility refused to part with the Africans in their households. He then petitioned the queen for a more powerful authorisation to expel the Africans out of the country.

- Despite the issuance of the privy council warrant, there is no evidence indicating that the deportation of Africans was pursued at the time.

- In 1601, Van Senden once again drafted a privy council letter, complaining that the blackamoors were ‘infidels, having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel’. This was not promulgated, hence, Van Senden’s scheme was unsuccessful.

- Following the Tudor reign was the Stuart rule in England, which brought about a change of status for the growing numbers of Black people in England.

- The 17th century saw English expansion throughout the Caribbean, as well as significant engagement in the transatlantic slave trade. In fact, a number of Caribbean territories were under English control by the 1650s.

- The status of Africans in England prior to this period, despite evidence indicating their independence, was ambiguous and appeared to have relied on individual experience.

- This changed as England became heavily involved in the slave trade.

- Many blackamoors continued to live as free members of society during the Stuart period.

- However, it became well established and popular to have Black domestic servants, particularly young children, in households across the country. Many were treated as enslaved people.

- Colonial slavery in English plantations was then instituted in the 1660s. Africans who were born or raised in the Caribbean would have been conditioned to see themselves as enslaved. Colonial officials, merchants, slave traders and plantation owners brought them back to England as servants and treated them as enslaved. Newspapers also increasingly carried advertisements for the sale of individual Black people. Enslaved Africans continued to be bought and sold in Britain during the 18th century, resulting in a significant growth of their population. The welcoming view of blackamoors’ legal status in the Tudor period soon changed, as there emerged a striking contrast in society’s attitudes towards people of colour.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/61/Black_Trumpeter_at_Henry_VIII%27s_Tournament_CROP_%28no_source%29.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/%28Putzger%29_Spanish_and_Portuguese_colonial_empires_in_16th_century.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/European%2C_likely_British_family_with_a_black_servant.png/800px-European%2C_likely_British_family_with_a_black_servant.png

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who were the Blackamoors?

The term "Blackamoors" historically referred to people of African descent, particularly those from North Africa, who were often depicted in European art and literature.

- What is the origin of the term "Blackamoors"?

The term "Blackamoor" is believed to have originated from the medieval Latin word "Maurus," which referred to the people of the ancient Roman province of Mauretania in North Africa. Over time, "Maurus" evolved into "Moor" or "Blackamoor," often used to describe people with dark skin.

- What role did Blackamoors play in European history?

Blackamoors were present in various roles throughout European history, including as soldiers, servants, musicians, and even as diplomats in royal courts. Their presence reflects the diverse interactions between Europe and Africa over centuries.