Roman Britain Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Roman Britain to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Roman Conquest

- Roman Influence on British Society

- Legacy and Decline

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Roman Britain!

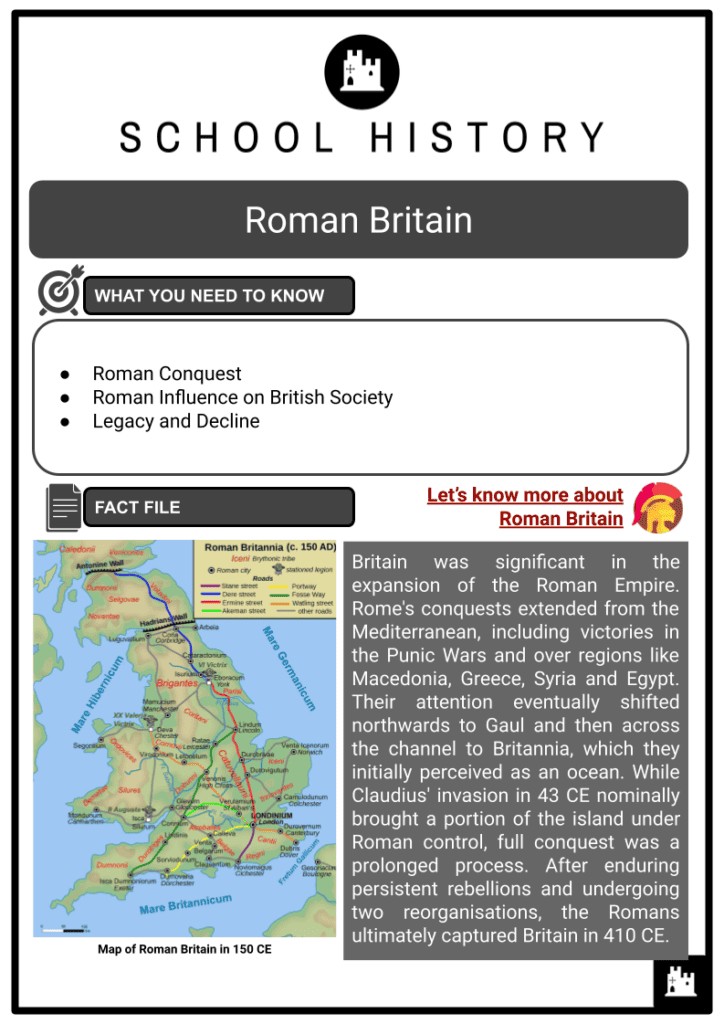

Britain was significant in the expansion of the Roman Empire. Rome's conquests extended from the Mediterranean, including victories in the Punic Wars and over regions like Macedonia, Greece, Syria and Egypt. Their attention eventually shifted northwards to Gaul and then across the channel to Britannia, which they initially perceived as an ocean. While Claudius' invasion in 43 CE nominally brought a portion of the island under Roman control, full conquest was a prolonged process. After enduring persistent rebellions and undergoing two reorganisations, the Romans ultimately captured Britain in 410 CE.

ROMAN CONQUEST

- Britain (formerly known as Albion) was predominantly made up of tiny agrarian tribal societies with enclosed villages at the time the Romans arrived. Many people from the south of Britain were of Belgian descent, and they spoke a language in common with the people of northern Gaul (present-day France and Belgium). In fact, trade between Transalpine Gaul increased after 120 BCE when the Britons began obtaining local imports like wine. There is even some evidence of a Gallo-Belgian currency.

Julius Caesar's Invasions

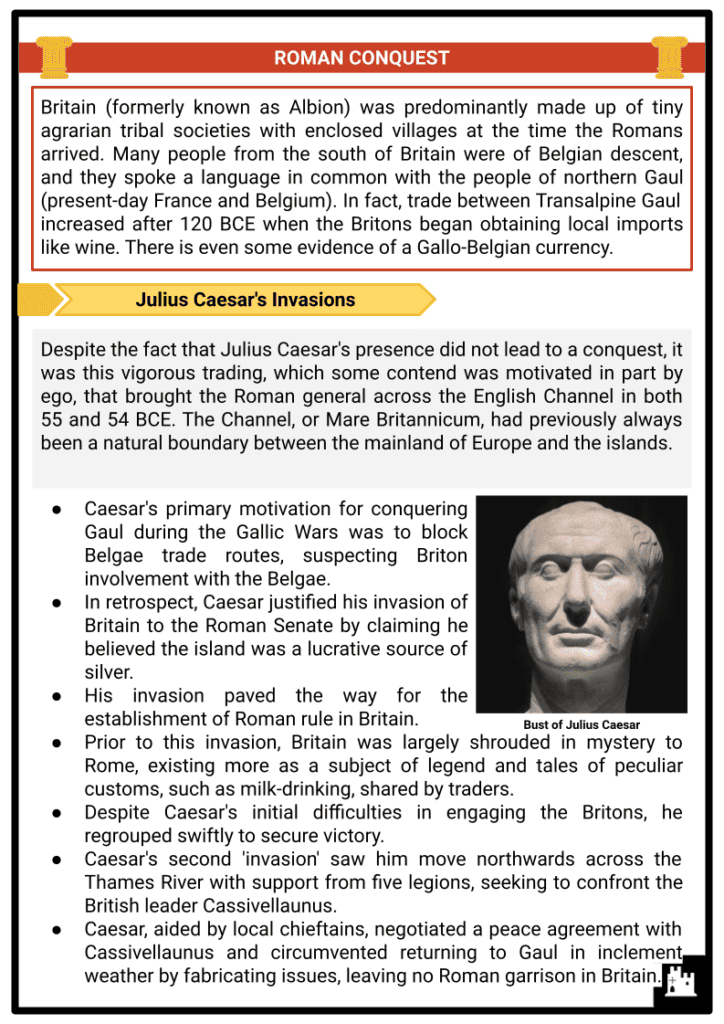

- Despite the fact that Julius Caesar's presence did not lead to a conquest, it was this vigorous trading, which some contend was motivated in part by ego, that brought the Roman general across the English Channel in both 55 and 54 BCE. The Channel, or Mare Britannicum, had previously always been a natural boundary between the mainland of Europe and the islands.

- Caesar's primary motivation for conquering Gaul during the Gallic Wars was to block Belgae trade routes, suspecting Briton involvement with the Belgae.

- In retrospect, Caesar justified his invasion of Britain to the Roman Senate by claiming he believed the island was a lucrative source of silver.

- His invasion paved the way for the establishment of Roman rule in Britain.

- Prior to this invasion, Britain was largely shrouded in mystery to Rome, existing more as a subject of legend and tales of peculiar customs, such as milk-drinking, shared by traders.

- Despite Caesar's initial difficulties in engaging the Britons, he regrouped swiftly to secure victory.

- Caesar's second 'invasion' saw him move northwards across the Thames River with support from five legions, seeking to confront the British leader Cassivellaunus.

- Caesar, aided by local chieftains, negotiated a peace agreement with Cassivellaunus and circumvented returning to Gaul in inclement weather by fabricating issues, leaving no Roman garrison in Britain.

- While many Romans applauded Caesar's journey across the English Channel, Caesar's deadliest foe Cato was appalled. The only items of any worth were enslaved people and hunting dogs, according to the Greek historian Strabo, who lived during the last Republic. Caesar placed more importance on the problems that were emerging in Gaul, a poor harvest, and potential insurrection. For another century, the Romans would not return to Britain.

Claudian Invasion and Establishment of Roman Rule

- Following Caesar's death and the ensuing civil war, the Roman Republic came to an end. The Romanisation of Gaul progressed under Emperors Augustus and Caligula, sparking a growing interest in Britain. While Augustus had other priorities, Caligula and his army considered the British Isles, though without any plans for an invasion – he simply had his soldiers throw javelins into the water. The unexpected conqueror of Britain turned out to be Claudius, an emperor deemed least likely for such a role.

- In 43 CE, Emperor Claudius, with an army led by Aulus Plautius, crossed the English Channel and landed at Richborough, initiating the capture of the island. Some speculate that Claudius, who had endured years of humiliation under Caligula, sought personal glory and acceptance through this endeavour. Despite spending only 16 days in Britain, Claudius took credit for the victory and celebrated a triumphant return to Rome in 44 CE.

Bust of Claudius - Claudius joined the Roman army during its northern advance towards the Thames River upon landing in Britain.

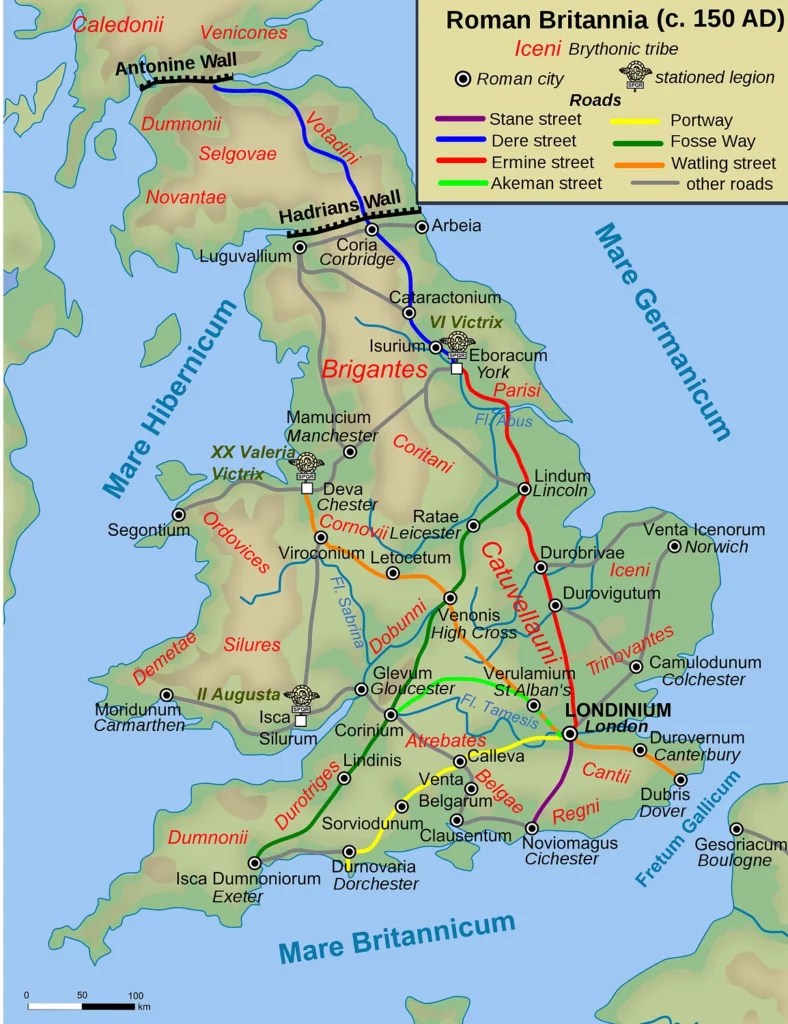

- The Roman army achieved a victory at Camulodunum (now Colchester), gaining control over Catuvellauni's territory.

- Following this triumph, the army rapidly expanded its dominion, extending north and westwards, resulting in Roman control over most of Wales and areas south of Trent by 60 CE.

- Client kingdoms, such as the Iceni in Norfolk and the Brigantes in the north, were established.

- The future emperor Vespasian led a second legion southwest, securing conquests of 20 tribal strongholds, while another legion was dispatched northwards.

- Cities like St Albans (Verulamium) and London (Londinium) were founded due to their strategic proximity to the English Channel.

Revolts & Consolidation

- Despite facing significant opposition, the Britons fiercely resisted Roman conquest. Caratacus, a member of the Catuvellauni tribe, gained widespread sympathy in Wales for his resistance efforts. However, he was eventually captured in 51 CE and sought refuge in a Brigantes-controlled area, where the queen swiftly handed him over to the Romans. Caratacus, along with his family, was taken in chains to Rome.

- Although Caratacus' uprising ultimately failed, Rome had yet to face the formidable Boudica. She was the wife of Prasutagus, the king of the Iceni tribe in eastern Britain, who was a Roman ally. Upon Prasutagus' death in 60 or 61 CE, his will divided his kingdom between Rome and his daughters. Rome, however, chose to seize the entire kingdom rather than share it.

- As a result, Boudica was whipped and her girls were sexually assaulted. Despite the fact that she and her army would ultimately lose, she got up, assembled an army, and joined forces with the nearby Trinovantes to launch an attack. Residents were slain, perhaps as many as 70,000, and towns, including Londinium, were pillaged and set afire.

- She asked the gods to grant her the just retribution the British deserved. Sadly, her pleas were not heard, and instead of giving herself up to the Romans, she killed herself. Tacitus thought that Britain would have been lost if it weren't for the timely action of the Roman ruler Gaius Suetonius Paulinus.

ROMAN INFLUENCE OF BRITISH SOCIETY

- The final major threat to Roman dominance in the lowlands came from the Battle of Watling Street. Along with his triumph against Boudicca, Paulinus also destroyed the Druid stronghold at Anglesey in an effort to increase the Roman presence there. The Druid religion had always been viewed as a danger to the Romans and their imperial cult.

- A change in Roman policy towards Britain resulted from the governor's very forceful reaction to Boudica's surrender, which also caused Rome to recall him and replace him with Turpilianus. The Britons were gradually adopting Roman practices. Rome's influence in Britain increased as it started to implement major changes. Burned-out cities were rebuilt. As the seat of government, London (Londinium) would soon have a basilica, a forum, a governor's residence, and a bridge over the Thames.

- Rome viewed the conquest of Britain as crucial, despite encountering slow progress in their endeavours.

- Contrary to Julius Caesar's initial assessment of little value, Britain held significant importance for its tax revenue and abundant mineral resources like tin, iron and gold, along with valuable commodities such as hunting dogs and animal furs.

- Mining activities experienced a notable expansion during this period.

- The island also contributed to the Roman Empire with its resources, including animals, grains and a steady supply of slaves.

- The construction of vital roads like Ermine Street (connecting London to York) and Watling Street (linking Canterbury to Wroxeter on the Welsh border) facilitated better connectivity and trade, attracting merchants and promoting economic growth.

- Despite the formidable military presence, resistance in Britain persisted, leading to a slower pace of territorial expansion.

Agricola's Campaign

- Ironically, Tacitus' father-in-law, military leader Gnaeus Julius Agricola, served as governor from 77 to 83 CE. Agricola had previously visited Britain. He had worked there as a military tribune while still a young man on Suetonius Paulinus' staff.

- Agricola was successful in a string of battles, conquering northern Wales before coming face to face with the Caledonians at Mons Graupius. The governor even declared that Ireland, an adjacent island, could be captured with just one legion. Unfortunately, Agricola was forced to leave Scotland when the emperor Domitian summoned one of his legions to fight invaders near the Danube. Agricola, despite his attacks on the insurgents, was not a brutal conqueror.

Hadrian's Wall & the Antonine Wall

- Unfortunately, Domitian, who was jealous of him, was aware of his achievement and called Agricola back. Scotland, the northern region he had long coveted, would take many more years to fully annexe. Emperor Hadrian would eventually construct a 73-mile-long stone and turf wall separating the province of Britain from the lands of the 'barbarians'.

- The emperor decided that the frontier needed to be protected in order to maintain peace after visiting both Gaul and Britain in 121 and 122 CE. He understood that the need to fortify frontier defences would increase with overseas expansion. Although it took years to construct and was guarded by 15,000 troops, it appears that it was only intended for patrols and observation rather than to keep the barbarians out.

- Britain had military garrisons set up by the year 130 CE. Rome began to recruit from the 'barbaric' provinces of the empire, particularly the Balkans and Britain, during this time as they realised the need to further bolster their army on the European continent.

- The 37-mile-long Antonine Wall, which bears the name of the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius, was constructed in 139 CE. However, it was too difficult to defend, so it was abandoned in 163 CE. It was located 100 km to the north between the Firth of Forth and the River Clyde.

LEGACY AND DECLINE

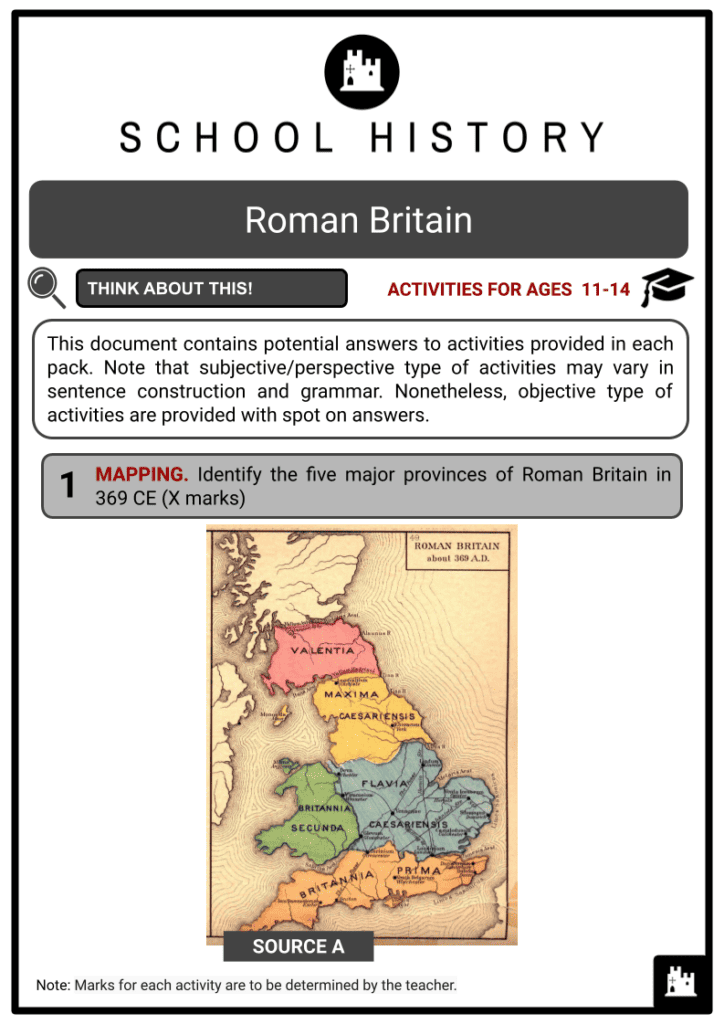

- The island quickly underwent more changes. The island was split in two to allow for more effective administration: Britannia Superior ruled from London and Britannia Inferior from York (Eboracum). The province was eventually divided into four distinct districts by Emperor Diocletian. As a result of Diocletian's tetrarchy, Britain came to be governed by the emperor in the west.

- Britain remained plagued by problems. The Picts of Scotland, the Scots of Ireland, and the Saxons of Germany had all attacked the island continuously during the third century CE. The Roman emperor of the west, Constantius, reclaimed power in 296 CE after a rebellion led by Carausius and later Allectus temporarily allowed Britain to become a separate state. The emperor had previously fought Celtic tribes while serving as a military tribune. He was given the well-deserved title of The Restorer of the Eternal Light by the citizens of London in honour of his victory.

Abandonment & Aftermath

- However, with the emergence of Christianity, Rome was having difficulty maintaining control of Britain by the end of the fourth century CE. After Alaric took control of Rome in 410 CE, the western half of the empire underwent a tremendous transformation that would eventually result in the loss of Spain, Britain and the majority of Gaul. The economic and cultural centre of the empire was the eastern half, which was located in Constantinople. Rome was doomed by the loss of its fertile, grain-producing regions.

- Historian Peter Heather, in The Fall of the Roman Empire, suggests that Britain was more prone to revolts or secession from Rome due to a perceived neglect of both its people and military forces, in contrast to other provinces receiving more attention, primarily for defence.

- In 367 CE, Emperor Valentinian I, after suppressing a Saxon rebellion, began a gradual withdrawal of his forces from Britain.

- Honorius, one of the final western emperors, completely withdrew Roman presence from the region in 410 CE.

- Honorius even sent directives to specific British cities, advising them to 'fend for themselves'.

- As a result, local governments were established, and Roman magistrates were ousted in the closing days of Roman rule in Britain.

- After the Roman withdrawal from Britain, the island's culture and population still retained traces of Roman influence. Contacts with Rome persisted, evidenced by a plea for aid directed to the Roman general Aetius in the fifth century CE, amid escalating Saxon invasions and attacks from Scotland and Ireland. Unfortunately, Aetius did not respond.

- This period saw Britain splinter into numerous small kingdoms as Europe entered the Dark Ages. In the late eighth century, the Vikings arrived, causing widespread turmoil for several decades. Ultimately, Alfred the Great emerged as a pivotal figure, successfully repelling the Viking invasion and proclaiming himself the King of England, leading to a resurgence of stability and strength in Britain.

- Roman Britain, like the rest of the empire, was a multicultural society where Black people could be found in every social levels and in locations as diverse as Cumbria, York, London and the South Coast of England, based on archaeological and written evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was life like in Roman Britain?

Life in Roman Britain varied depending on one's social status. Romans introduced new technologies, roads, and architecture. Towns and cities flourished, and the economy improved. However, life for the common people, especially enslaved people, could be harsh.

- What language did the Romans speak in Britain?

The Romans spoke Latin in Britain. Latin inscriptions and texts have been found throughout the region.

- How long did Roman rule last in Britain?

Roman rule in Britain lasted for about 400 years, from 43 CE to the early 5th century, when the Romans withdrew their legions.