Josephine Butler Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Josephine Butler to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early Life and Education

- Personal Life

- Contributions to Women's Rights

- Campaign Against the Contagious Diseases Acts

- Exposing Child Prostitution

- Later Years and Death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Josephine Butler!

Josephine Elizabeth Butler was a British feminist and social reformer in the Victorian era who dedicated her life to advocating for the rights and welfare of marginalised women and children. She is best known for her work in campaigning against the sexual exploitation of women, particularly in the regulation of prostitution.

Josephine's relentless work resulted in multiple legal changes and enhancements in the care and safeguarding of vulnerable women. Her advocacy and dedication to social justice have had a lasting impact on the history of women's rights, serving as a source of inspiration for generations of activists and reformers.

Early Life and Education

- Josephine Elizabeth Grey (later Butler) was born on 13 April 1828, in Milfield, Northumberland, England. She was the fourth daughter and seventh child of Hannah Annett and John Grey, a land agent and agricultural expert who was a relative of the reformist British Prime Minister, Lord Grey.

- Josephine received home education before transferring to a boarding school in Newcastle upon Tyne, where she studied for two years. Her father taught her and her siblings about politics and social issues and introduced them to many politically significant visitors. Even at a young age, Josephine showed great intellectual promise and excelled in her studies.

- Her father's political activities and beliefs greatly influenced her, as did the religious teachings of her mother. Her familial history and social connections influenced her to develop a strong sense of social responsibility and unwavering religious beliefs.

- However, at the age of 17, Josephine experienced a theological crisis likely triggered by seeing the body of a suicide victim while she was horseback riding. She was disillusioned with her monthly church visits. After her crisis, Josephine did not align herself with any specific denomination of Christianity and continued to be sceptical of the Anglican Church.

- Josephine visited her brother in County Laois, Ireland, in mid-1847. During the peak of the Great Famine, she encountered extensive suffering among the impoverished for the first time, which severely touched her.

Personal Life

- Josephine, as a member of Exeter College, Oxford, met George Butler in 1850. In October of that year, George began mailing her poems that he had written himself. The pair got engaged in January 1851 and married in January 1852.

- The couple had four kids: George, Arthur Stanley, Charles and Evangeline Mary. Unfortunately, two of their children, Arthur and Evangeline, died at a young age.

- The Butlers had a home at 124 High Street, Oxford. Josephine's recollections of Oxford were of a secluded and misogynistic society devoid of family connections, where she frequently found herself as the sole woman at social events. As a way to help, she and George aided several fallen women in Oxford by inviting some to live in their house.

- As George pursued his studies in Oxford, Josephine was exposed to the intellectual and academic environment of the university town. This experience further fuelled her desire for knowledge and education, inspiring her to become a lifelong advocate for women's access to education and intellectual pursuits.

- In 1856, Josephine's family moved to Clifton, near Bristol. A decade later, they moved to Liverpool, where her husband was appointed headmaster of Liverpool College. The couple continued their social work to provide shelter and support for vulnerable women, particularly those who had been forced into prostitution.

Contributions to Women's Rights

- Josephine Butler made significant contributions to women's rights during the 19th century, particularly in the areas of education, labour rights and sexual exploitation. She had a strong commitment to social justice and held that every person has inherent worth and deserves respect, regardless of their gender.

- One of her most notable contributions was in the field of education. While in Liverpool, Butler campaigned for improved educational opportunities for women, believing that it was essential for empowering women and promoting gender equality. She fought for the establishment of school boards that would provide education for all children, regardless of their gender.

- In 1867, Josephine co-founded, with suffragist Anne Clough, the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women to raise the status of governesses and female instructors into a profession. She held the position of president until 1873.

- In 1868, Josephine authored The Education and Employment of Women, promoting women's access to further education and equal employment prospects.

- This would be her first publication out of a total of 90 that she authored during her lifetime. In May of the same year, she requested the Cambridge senate create exams for women, leading to the introduction of the Cambridge Higher Examination in 1869.

- In addition to her work in education, Josephine was also a staunch supporter of labour rights for women. She sought to improve the working conditions of women, particularly those in impoverished and marginalised communities. Her advocacy aimed to secure better wages, improved working conditions, and overall fair treatment for women in the labour force.

- Furthermore, Josephine was a prominent advocate in the battle against sexual exploitation and the safeguarding of women from the atrocities of prostitution. She campaigned vigorously for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which unjustly targeted and subjected women to medical examination and treatment without their consent. Her persistent efforts resulted in the eventual repeal of these discriminatory laws, signifying a notable victory in the fight for women's rights.

Campaign Against the Contagious Diseases Acts

- Josephine Butler's commitment to social justice and women's rights extended to her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts, or CD Acts.

- During the Victorian era in England, working-class women commonly turned to prostitution due to a number of socio-economic issues. Even though prostitution helped many poor women survive, Victorian values considered it shameful and immoral.

- Uncertainty in 19th-century statistics hindered the assessment of whether prostitution was on the rise or decline during this era. However, it is certain that Victorians in the 1840s and 1850s believed that prostitution and venereal illness were on the rise.

- The government aimed to control the high prevalence of venereal disease among its armed personnel by regulating prostitution. In 1864, one-third of medical cases in the army were due to venereal disease, with hospital admissions for gonorrhoea and syphilis reaching 290.7 per 1,000 troops. Prostitutes targeted customers in the military, taking advantage of servicemen's enforced abstinence and the harsh living conditions in the barracks.

- As a result, the UK parliament passed the CD Acts in 1864, with modifications made in 1866 and 1869. The Acts sanctioned the forcible examination and treatment of women suspected of being involved in prostitution.

- Before the Acts, the number of troops decreased significantly from 83,386 to 59,758 over 6 years. The Committee on the Contagious Diseases Acts presented evidence in 1879 indicating that various factors other than venereal disease contributed to the decrease in cases.

- Some men were discharged for venereal diseases, while others were discharged for bad character. There was also a notable decrease in military recruitment.

- Moreover, doctors noted that the only progress seen after the Acts was in the management of venereal illness, but it had minimal effect on its transmission. Therefore, the effectiveness of the Acts in reducing the spread of venereal disease is uncertain.

- Under the Acts, women who were declared to be infected were kept in lock hospitals or wards where conditions were occasionally poor. An 1882 assessment found that there were 402 beds available for female patients in all voluntary lock hospitals in Great Britain, but only 232 beds were paid for usage. For lock hospital shortages, female venereal patients were sent to workhouse infirmaries.

- Depending on the city, the lock hospital and asylum may have operated together. Women were treated in asylums for moral deviation. The idea was to 'cure' prostitutes of their sexual impulses because they were deviant. The general public liked asylum treatment more because of Victorian 'respectability' expectations.

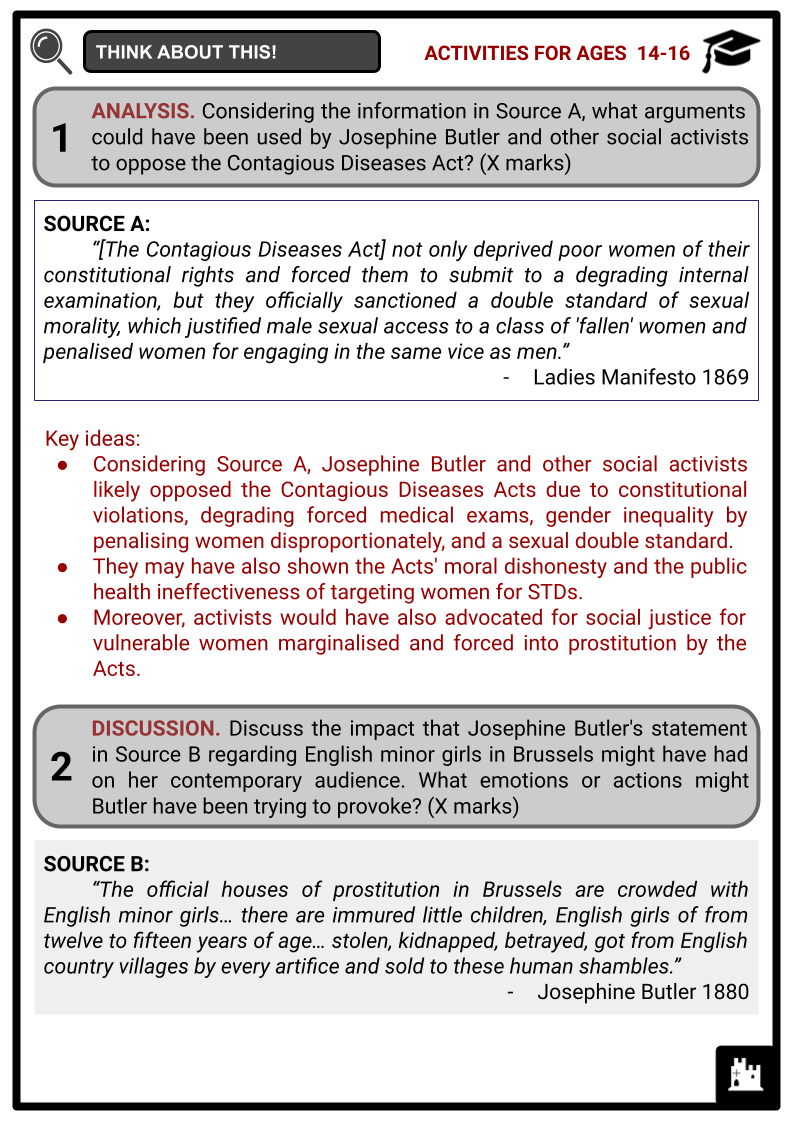

- The Acts were rooted in the demeaning belief that these women were responsible for the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, and it led to their unjust and degrading treatment under the guise of public health.

- In 1869, Josephine strongly objected to the Acts after learning about them. She identified the Acts as infringing on women's physical autonomy and perpetuating gender-based discrimination. On 31 December of the same year, the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts (LNA) was formed.

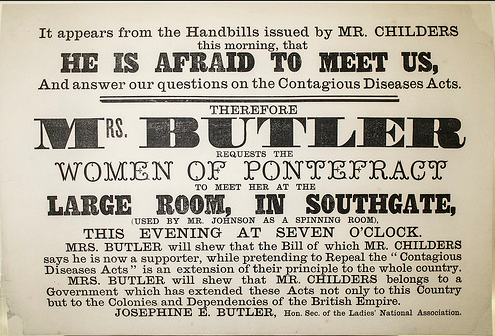

- As part of the campaign, Butler travelled to Britain in 1870, visiting 99 meetings in the course of the year.

- She concentrated on getting support from working-class family men who were upset about the intrusive examinations women underwent, which she referred to as surgical or steel rape. She managed to convince numerous audience members despite encountering strong resistance.

- The collapse of the Liberal administration in 1874 halted the repeal effort for the Contagious Diseases Acts, which had official backing. The LNA's attempts to convince Liberal MPs to oppose the Acts were progressing slowly.

- In December 1874, Josephine journeyed to Europe, where she engaged with female organisations and civic officials. She established the British and Continental Federation for the Abolition of Prostitution, subsequently known as the International Abolitionist Federation, to advocate against government control of prostitution and to work towards ending female enslavement.

- The 1880 general election resulted in the displacement of Disraeli's Conservative Party and the ascension of Gladstone's second cabinet, which advocated for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. Political pressure from Liberal backbenchers resulted in growing opposition to the Acts.

- In February 1883, the House disapproved of the mandatory examination of women under the Acts. After discussing the proposal, MPs decided to stop the inspections by a wide margin in April.

- Josephine's campaign resonated with many, and she gained widespread support from various segments of society – activists, intellectuals and everyday citizens – galvanising a unified call for justice. Finally, on 6 April 1886, after 17 years of relentless campaigning, the controversial Contagious Diseases Acts were repealed.

Exposing Child Prostitution

- In 1885, Josephine Butler met Florence Soper Booth, the daughter-in-law of William Booth, who founded the Salvation Army. The two joined forces to expose child prostitution in Britain.

- Along with other allies, Florence and Josephine convinced The Pall Mall Gazette editor, William Thomas Stead, to support their cause. Stead believed that the most effective way to demonstrate the occurrence of purchasing young girls for prostitution was to personally buy a girl.

- Josephine met Stead with a former prostitute and brothel proprietor who was residing in her hostel. Stead bought a 13-year-old girl from her mother for £5 in a Marylebone slum and brought her to France. Josephine's article, titled 'The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon', revealed the prevalence of child prostitution in London.

- Josephine delivered a speech advocating for enhanced protection for youth and the elevation of the age of consent. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 was approved, increasing the legal age of consent from 13 to 16 years old and criminalising the act of procuring girls for prostitution through drugs, coercion or deception.

Later Years and Death

- In her later years, Josephine Butler continued to be an influential figure in the fight for women's rights. She remained an active advocate for the well-being of women and girls, dedicating her life to addressing the systemic issues that perpetuated their exploitation.

- Although the Contagious Diseases Acts were repealed in the UK in 1886, they were nonetheless enforced in India, where prostitutes near British cantonments were regularly subjected to forced examinations.

- Major-General Edward Chapman implemented the legislation found in the Special Cantonments Acts. Josephine initiated a campaign to abolish the legislation by drawing parallels between the girls and the enslaved.

- In June 1888, the House of Commons unanimously passed a resolution to rescind the legislation, instructing the Indian government to revoke the Acts. To bypass this directive, the India Office recommended to the Viceroy of India that it introduce new laws requiring suspected prostitutes with contagious diseases to undergo an examination or risk being expelled from the cantonment.

- As her husband's health deteriorated, Josephine devoted more time to caring for him. In 1889, they journeyed to Naples and caught influenza during the 1889–90 epidemic. Following his passing, Josephine relocated to Wimbledon, London, where she dedicated four months to compiling a detailed report demonstrating the ongoing operation of lock hospitals, mandatory examinations and the exploitation of young prostitutes.

- Starting in 1901, Josephine gradually disengaged from public activities, stepping down from her roles in campaign groups and dedicating more time to her family. On 30 December 1906, Josephine passed away in Wooler, Northumberland. Her body was buried in the nearby village of Kirknewton. Despite her death, her legacy lived on through the impact of her advocacy and activism.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Josephine Butler?

Josephine Butler was a prominent British feminist, social reformer, and advocate for women's rights in the 19th century.

- What were Josephine Butler's major contributions?

Butler campaigned vigorously for the rights and dignity of women, particularly those who were marginalised and vulnerable. She focused on issues such as the welfare of prostitutes, women's education, and the repeal of laws that oppressed women.

- What was Josephine Butler's role in the campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts?

Butler played a central role in the campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts, which allowed for the forcible medical examination and detention of women suspected of being prostitutes. She led a nationwide movement to repeal these laws, arguing that they violated women's rights and perpetuated harm rather than addressing the root causes of prostitution.