Lord Kitchener Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Lord Kitchener to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life

- Kitchener and His Military Career

- Kitchener during the First World War

- Death and Legacy of Kitchener

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Lord Kitchener!

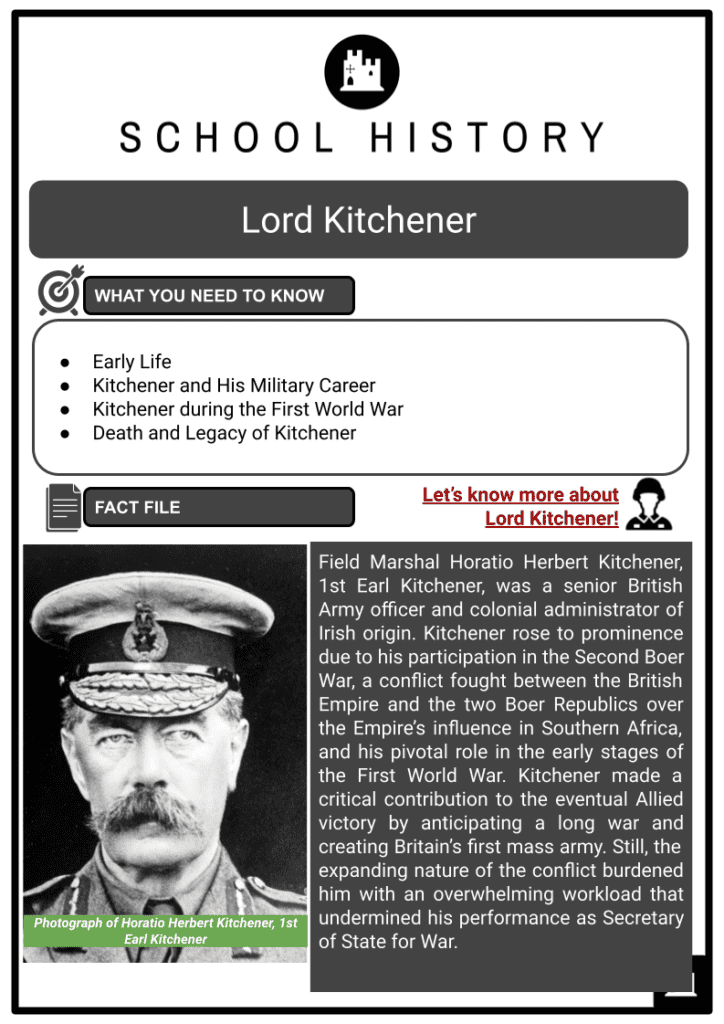

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator of Irish origin. Kitchener rose to prominence due to his participation in the Second Boer War, a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics over the Empire’s influence in Southern Africa, and his pivotal role in the early stages of the First World War. Kitchener made a critical contribution to the eventual Allied victory by anticipating a long war and creating Britain’s first mass army. Still, the expanding nature of the conflict burdened him with an overwhelming workload that undermined his performance as Secretary of State for War.

EARLY LIFE

- On 24 June 1850, Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born in Ireland. His father, Henry Horatio Kitchener, was a retired lieutenant colonel, and his mother, Frances Anne Chevallier, was 20 years younger than Henry. Kitchener’s clan could be traced back to the reign of Prince of Orange William III on both sides of his family, and his mother’s line was of French Huguenot heritage. Kitchener was 14 years old when his mother died in Switzerland, and his father remarried two years later.

- The newlyweds relocated to New Zealand, but he and his siblings remained in Switzerland to attend school. When his mother was still alive, she was concerned about her son’s oversensitivity and lack of interest in manly pursuits. Herbert’s father insisted on home tuition, although Herbert was challenging to instruct. One tutor stated that he had never met a youngster who was so lacking in educational fundamentals. His lack of learning made him a laughingstock among his classmates, and the humiliation left a permanent mark on him. However, he had a talent for languages and became fluent in French and German.

KITCHENER AND HIS MILITARY CAREER

- Kitchener graduated from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in December 1870 before joining the Royal Engineers. He spent much of his early career in the Middle East and Egypt. In 1874, at 24, Kitchener was sent to a mapping survey of the Holy Land by the Palestine Exploration Fund, replacing Charles Tyrwhitt-Drake, who had died of malaria.

- With fellow officer Claude R Conder, they surveyed Palestine between 1874 and 1877, returning to England only briefly in 1875 after an attack by locals at Safed in Galilee. Because their work was mostly confined to the area west of the Jordan River, Kitchener and Conder’s expedition became known as the Survey of Western Palestine.

- The Survey of Western Palestine culminated in the most extensive and accurate map of Palestine published in the 19th century, consisting of 26 sheets. The PEF survey was the pinnacle of cartographic work in Palestine throughout the 19th century.

- After completing the survey of Western Palestine, Kitchener was dispatched to Cyprus to assess the newly acquired British protectorate.

- In 1879, he was appointed vice-consul in Anatolia.

KITCHENER IN EGYPT

- On 4 January 1883, Kitchener was promoted to captain, given the Turkish title binbasi or major, and sent to Egypt to help rebuild the Egyptian Army. Egypt had become a British puppet state, with British officers commanding its army, although ostensibly under the rule of the Khedive, an Egyptian ruler and his nominal overlord, the Sultan of Turkey.

- In February 1883, Kitchener was appointed second-in-command of an Egyptian cavalry regiment. In late 1884, he took part in the failed Nile Expedition to relieve Charles George Gordon, a British army officer in Sudan.

- Kitchener was promoted to brevet major on 8 October 1884, and brevet lieutenant-colonel on 15 June 1885, and became the British representative on the Zanzibar boundary commission in July 1885. Kitchener was advanced to brevet colonel on 11 April 1888, and to major on 20 July 1889, and led the Egyptian cavalry at the Battle of Toski in August 1889. He was named Inspector General of the Egyptian Police from 1888 to 1892 before becoming Adjutant-General of the Egyptian Army in December of that year and Sirdar or Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army with the local rank of brigadier in April 1892.

- In November 1899, he was appointed the first District Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England’s District Grand Lodge of Egypt and Sudan.

KITCHENER IN SUDAN AND KHARTOUM

- Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister at the time, was concerned with keeping France out of the Horn of Africa.

- A French expedition led by Jean-Baptiste Marchand left Dakar in March 1896 to conquer Sudan, seizing control of the Nile as it flowed into Egypt and driving the British out of Egypt, restoring Egypt to its pre-1882 position within the French sphere of influence.

- Salisbury believed the French would take over Sudan if the British did not.

- With the Italians failing and the Mahdiyah state threatening to take Eritrea, Salisbury directed Kitchener to invade northern Sudan, ostensibly to divert the Ansar from assaulting the Italians.

- The Ansar is a Sudanese Sufi religious sect whose adherents are disciples of Muhammad Ahmad, a Sudanese spiritual leader centred on Aba Island who declared himself Mahdi on 29 June 1881.

- Kitchener scored successes at the Battle of Ferkeh in June 1896, in which a Mahdist Sudanese army was surprised and beaten by Egyptian forces led by Kitchener, earning him national fame in the United Kingdom (UK) and promotion to major-general on 25 September 1896. Kitchener desired to create a railway to support the Anglo-Egyptian army and entrusted the Sudan Military Railroad to a Canadian railway builder, Percy Girouard, whom he had particularly requested.

- Kitchener had further victories at the Battle of Atbara in April 1898, during the Second Sudan War, and the Battle of Omdurman in September 1898, during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British-Egyptian expeditionary force and a Sudanese army of the Mahdist Islamic State.

- The Mahdist Islamic State was founded in 1881 on a religious and political movement against Egypt’s Khedivate, which had controlled Sudan since 1821.

- In September 1898, Kitchener was appointed Governor-General of Sudan and began a programme to restore decent administration. The initiative had a solid foundation, with education at Gordon Memorial College serving as its centrepiece – and not only for the children of the local elites but for children from all walks of life. He renovated Khartoum’s mosques, introduced changes that made Friday the Muslim holy day, the official day of rest, and guaranteed religious freedom to all Sudanese residents. He tried to stop evangelical Christian missionaries from converting Muslims to Christianity.

- Gordon Memorial College was a university in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. It was named after British army General Charles George Gordon, who was murdered during the Mahdi rebellion in 1885, and it was officially opened on 8 November 1902, by Kitchener himself.

KITCHENER DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR

- Kitchener arrived in South Africa on the RMS Dunottar Castle during the Second Boer War with Field Marshal Lord Roberts and enormous British reinforcements in December 1899.

- Kitchener was officially the chief of staff, but in practice, he was a second-in-command who was present for the liberation of Kimberley before directing an unsuccessful frontal assault at the Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900.

- Following the defeat of the conventional Boer forces in November 1900, Kitchener took over as general commander from Roberts. On 29 November 1900, he was appointed lieutenant-general and on 12 December 1900, he was promoted to local general. Following a difficult six months, the Treaty of Vereeniging, which ended the War, was signed in May 1902. During this time, Kitchener was at odds with the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Alfred Milner, and the British government.

Political cartoon from 1898 depicting Kitchener’s efforts to secure funds for the establishment of the college - Milner was a hardline conservative who wanted to Anglicise the Afrikaner people (the Boers), and Milner and the British government wanted to assert victory by forcing the Afrikaner to sign a humiliating peace treaty. Kitchener preferred a more generous compromise peace treaty that recognised certain Afrikaner rights and promised future self-government.

- Kitchener even considered a peace settlement suggested by Louis Botha and other Boer leaders, although he knew the British administration would reject the offer.

- Louis Botha was the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, the forerunner of the modern South African state.

- During his time in South Africa, Kitchener served as acting High Commissioner of South Africa and administrator of the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies. Kitchener, raised to the substantive rank of general on 1 June 1902, was given a farewell reception in Cape Town on 23 June before departing for the United Kingdom on the SS Orotava.

KITCHENER IN INDIA

- Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief in India in late 1902 and arrived in November to take up the position in time for the January 1903 Delhi Durbar. He immediately set about reorganising the Indian Army.

- While the Viceroy, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, who had originally advocated for Kitchener’s appointment, supported many of his reforms, the two men eventually clashed.

- Curzon was correct to oppose Kitchener’s attempts to consolidate all military decision-making power in his own office. Although the same person now held the offices of Commander-in-Chief and Military Member, senior officers could only approach the Commander-in-Chief directly. To deal with the Military Member, a request was made through the Army Secretary, who reported to the Indian Government and had access to the Viceroy. In 1905, Kitchener presided over the Rawalpindi Parade to commemorate the visit of the Prince and Princess of Wales to India. Kitchener founded the Indian Staff College in Quetta the same year, where his image still hangs. In 1907, his time as Commander-in-Chief of India was extended by two years.

KITCHENER DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR

- At the start of the First World War, British Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith promptly named Kitchener Secretary of State for War. Asquith had been filling the role personally as a stopgap following Colonel John Edward Bernard Seely’s resignation over the Curragh Incident earlier in 1914. Kitchener was on his usual summer leave in Britain between 23 June and 3 August 1914 and had boarded a cross-Channel boat to begin his return voyage to Cairo when he was summoned to London to meet with Asquith. The following day, at 11 pm, war was declared.

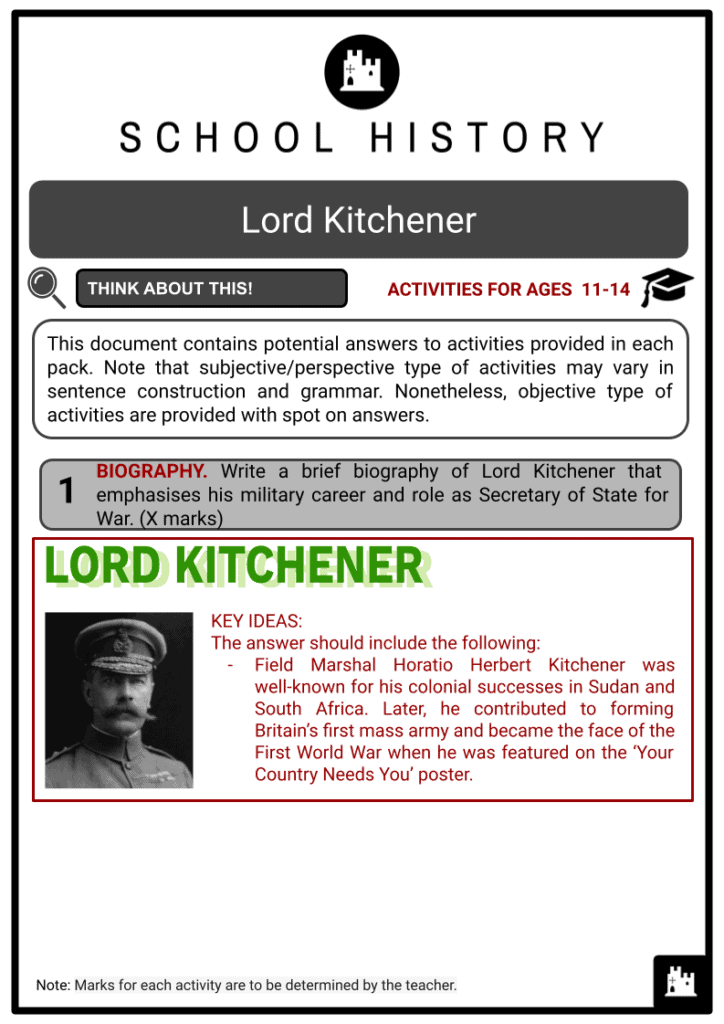

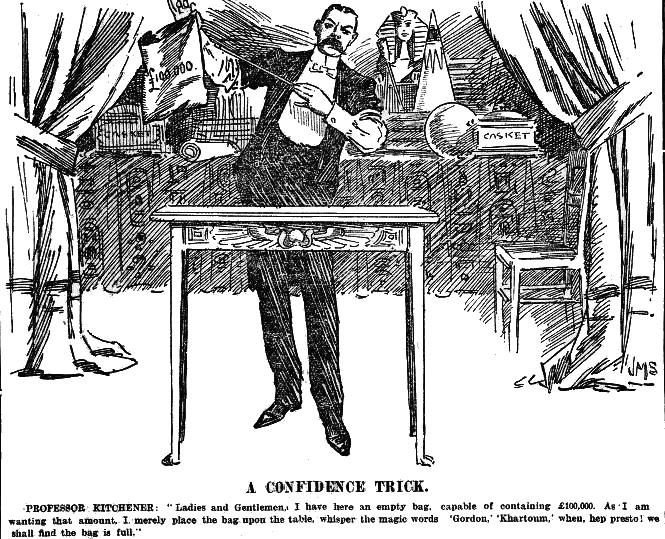

The iconic poster of Kitchener

1914

- Despite cabinet opposition, Kitchener rightly projected a long war that would take at least three years, necessitate massive new armies to beat Germany and result in massive casualties before the finish.

- A large recruitment effort was launched, which soon featured a characteristic poster of Kitchener stolen from the front cover of a magazine.

- On 5 August, Kitchener and Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Haig advocated that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) should be placed at Amiens, where it could launch a strong counterattack once the German advance route was revealed.

- Kitchener’s desire to concentrate further back at Amiens may have been affected by a mostly accurate map of German dispositions published in The Times on the morning of 12 August by Repington.

- Sir John French, the BEF commander in France, considered removing his soldiers from the Allied line due to substantial British losses at the Battle of Le Cateau. By 31 August, French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre, President Raymond Poincaré and Kitchener had all sent him messages pleading with him not to. On 1 September, Kitchener travelled to France for a meeting with Sir John after being authorised by a midnight meeting of whomever Cabinet Ministers could be located.

1915

- Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the BEF, and other senior commanders agreed in January 1915 that the New Armies should be absorbed into existing divisions as battalions rather than sent out as complete divisions.

- In the context of Cabinet deliberations about invasions on the Baltic or North Sea coasts or against Turkey, Kitchener cautioned the French in January 1915 that the Western Front was a siege line that could not be overcome.

- To relieve pressure on the Western Front, Kitchener proposed an assault on Alexandretta with the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), New Army and Indian soldiers. Alexandretta was a Christian-majority province and the critical hub of the Ottoman Empire’s railway network. Its capture would have split the Empire in half.

- Nonetheless, Kitchener was convinced to support Lieutenant Colonel Winston Churchill’s disastrous military expedition, the Gallipoli Expedition, in 1915–1916.

- On the other hand, Kitchener warned a parliamentary committee as late as mid-October 1915 that leaving the peninsula would be the most devastating event in the Empire’s history.

- Kitchener remained unpopular among politicians and professional soldiers. He felt it repugnant and unnatural to discuss military secrets with a huge number of gentlemen he had just met.

1915

- On 21 October, Kitchener urged the Dardanelles Committee that Baghdad be conquered for prestige and then abandoned due to logistical difficulties. Although his advice was no longer unquestioned, the British forces were eventually besieged and captured at Kut.

1916

- Early in 1916, Kitchener visited Douglas Haig, the recently appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France. Kitchener had played a crucial role in the deposition of Haig’s predecessor, Sir John French, with whom he had a strained relationship.

- Kitchener was sceptical of Haig’s strategy to win a decisive victory in 1916, preferring smaller and purely attritional operations, but agreed with the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir William Robert Robertson, when he told the Cabinet that the planned Anglo-French onslaught on the Somme should go forward.

- French Prime Minister Aristide Briand pressured Kitchener to launch an attack on the Western Front to relieve the pressure from the German attack at Verdun.

- On 2 June 1916, Kitchener personally received questions from lawmakers concerning his management of the war effort. Before the outbreak of hostilities, Kitchener had ordered two million guns from several United States (US) armaments manufacturers.

- By 4 June 1916, just 480 rifles had arrived in the UK. The amount of shells provided was less than the expected numbers of shells. The 200 Members of Parliament (MPs) who had assembled to interrogate him applauded him for his honesty as well as his efforts to keep the troops armed. Sir Ivor Herbert, a British Army Officer who had introduced the failed vote of censure in the House of Commons a week before, personally seconded the motion.

DEATH AND LEGACY OF KITCHENER

- Kitchener had paid particular attention to the deteriorating situation on the Eastern Front amid his other political and military responsibilities. This included supplying large quantities of war equipment to the Russian army, which had been under increasing pressure since mid-1915.

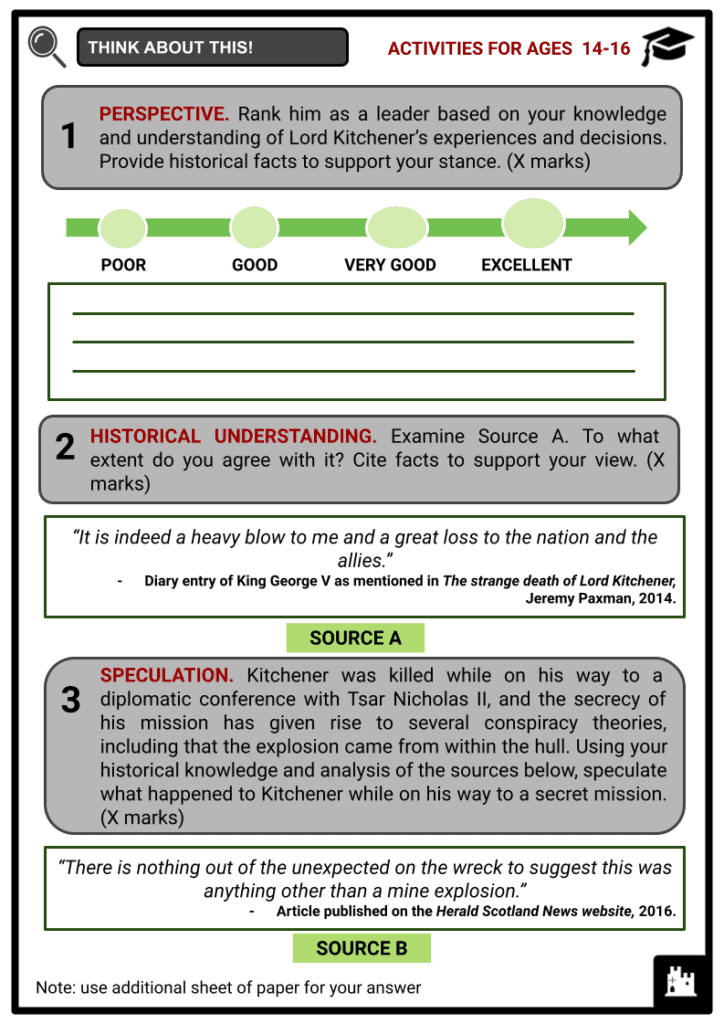

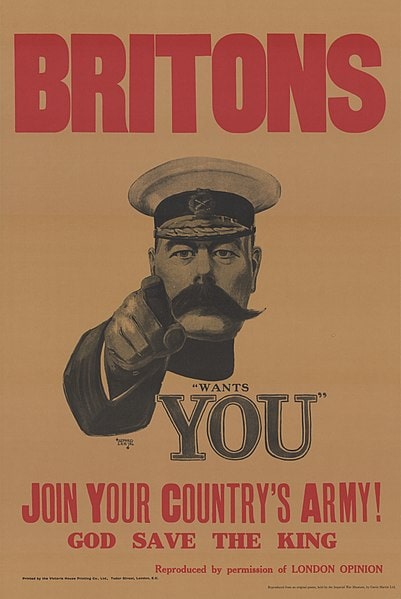

One of the last photographs taken of Kitchener - In May 1916, Chancellor of the Exchequer Reginald McKenna proposed that Kitchener lead a special and confidential mission to Russia to discuss munition shortages, military strategy, and financial problems with the Imperial Russian Government and the Stavka, which was now under Tsar Nicholas II’s command.

- The Stavka is the name of the top command of the armed forces in the former Russian Empire, Soviet Union and Ukraine.

- Kitchener then embarked on the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire for Russia. Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe changed Hampshire’s route at the last minute due to misinterpreting the weather forecast and ignoring recent intelligence and observations of German U-boat activity along the amended course.

- The Hampshire hit a mine planted by the freshly launched German U-boat U-75 and sank west of the Orkney Islands shortly before 7.30pm that same day while steaming for the Russian port of Arkhangelsk in a force nine gale.

- Only 12 soldiers escaped. All 10 members of Kitchener’s team were killed. Kitchener was spotted standing on the quarterdeck during the 20-minute sinking of the ship. Kitchener’s body was never found.

- Kitchener’s fame, the suddenness of his death, and its apparent convenient timing for several parties all gave birth to a slew of conspiracy theories concerning his death almost immediately. One in particular was presented by Lord Alfred Douglas, who claimed a link between Kitchener’s death, the current naval Battle of Jutland, Churchill, and a Jewish plot. Churchill prevailed in what proved to be the final successful instance of criminal libel in British legal history, and Douglas was imprisoned for six months.

- In 1926, a hoaxster named Frank Power reported in the Sunday Referee newspaper that a Norwegian fisherman had discovered Kitchener’s remains. Power returned from Norway with a casket and prepared it for burial at St Paul’s Cathedral.

- However, the authorities interfered, and police and a prominent pathologist opened the casket. For weight, the box was discovered to contain solely tar. Power sparked great public uproar, but he was never convicted.

- Kitchener is formally memorialised in a chapel near the main entrance of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, where a memorial ceremony was held in his honour. Following a 1916 referendum, the city of Berlin, Ontario, which was named after a substantial German immigrant settler community, was renamed Kitchener. Some historians now appreciate his strategic vision during the First World War, particularly his role in laying the framework for expanding munitions production and his pivotal role in expanding the British army in 1914 and 1915, establishing a force capable of meeting Britain’s continental commitment.

Image Sources

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lord_Kitchener_AWM_A03547.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:A_Confidence_Trick_-_JM_Staniforth.png

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:30a_Sammlung_Eybl_Gro%C3%9Fbritannien._Alfred_Leete_(1882%E2%80%931933)_Britons_(Kitchener)_wants_you_(Briten_Kitchener_braucht_Euch)._1914_(Nachdruck),_74_x_50_cm._(Slg.Nr._552).jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kitchener_boarding_HMS_Iron_Duke_5_June_1916_IWM_HU_66128.jpg

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is Lord Kitchener most famous for?

Lord Kitchener is most famous for his iconic "Your Country Needs You!" recruitment poster during World War I. This poster became an enduring symbol of British wartime propaganda.

- Did Lord Kitchener serve in World War I?

Yes, Lord Kitchener served as the British Secretary of State for War during World War I. He played a crucial role in organising and expanding the British Army to meet the demands of the war.

- How did Lord Kitchener die?

Lord Kitchener died when the HMS Hampshire, the ship he was travelling on, struck a mine and sank off the coast of Scotland in 1916. His death was a significant loss for the British war effort during World War I.