The Bahamas Colony Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about The Bahamas Colony to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Beginning of European settlement of the Caribbean

- British colonisation of the Caribbean

- Early English settlement of the Bahamas

- Development in the Bahamas colony

- Road to independence

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Bahamas Colony!

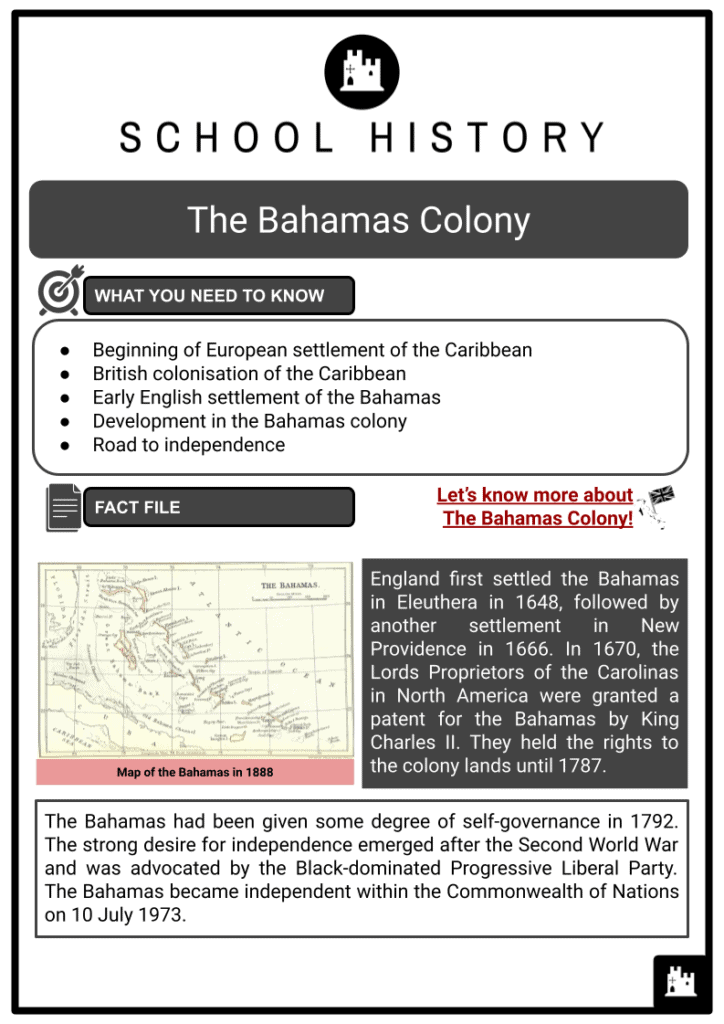

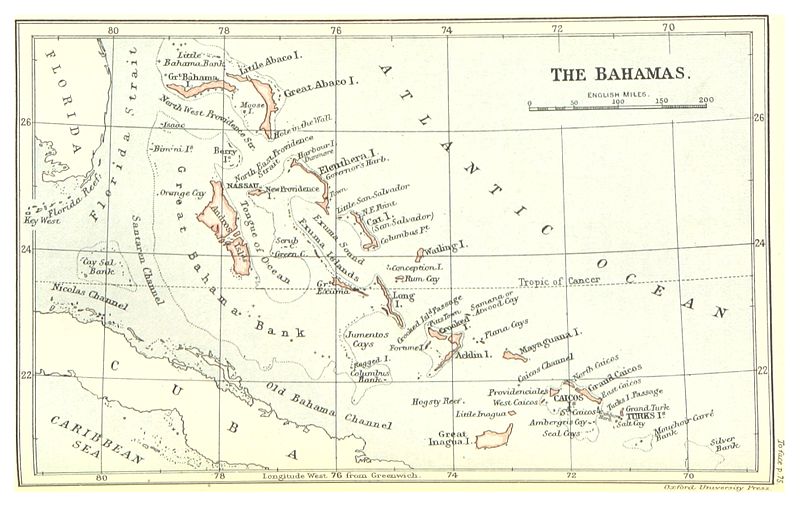

England first settled the Bahamas in Eleuthera in 1648, followed by another settlement in New Providence in 1666. In 1670, the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas in North America were granted a patent for the Bahamas by King Charles II. They held the rights to the colony lands until 1787. The Bahamas had been given some degree of self-governance in 1792. The strong desire for independence emerged after the Second World War and was advocated by the Black-dominated Progressive Liberal Party. The Bahamas became independent within the Commonwealth of Nations on 10 July 1973.

Beginning of European settlement of the Caribbean

- The Caribbean was first colonised by Spain when the Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492 and claimed the already populated region for Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. The region became known as the West Indies because Columbus believed that he had sailed to the ‘Indies’, as Asia was called at that time. He also referred to all the people he met in the region as ‘Indians’. Europeans during this period were unaware that the Caribbean was an entirely new part of the world now known as the Americas.

- Permanent Spanish settlement began in 1493.

- After having claimed the entire Caribbean and finalised the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) with Portugal, the Spanish mainly confined their settlement to the larger islands of Hispaniola.

- The Spanish also found settlements in other parts of the region in the early 16th century.

- They also carried on their explorations of islands and the lands surrounding the Caribbean Sea looking for sources of concentrated Indigenous populations and rich deposits of gold and silver.

- The Spanish colonisation of the Caribbean during this period established persistent administrative, social and cultural patterns that would be replicated throughout the Americas.

- The impact of Spanish contact and oppression on the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean had lasting and serious consequences for them.

- During a significant portion of the 16th century, Spain maintained its own distinct system in the region.

- The Spanish Crown soon turned away its main focus from the Caribbean following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire and the succeeding conquest of Peru.

British colonisation of the Caribbean

- Spain and Portugal practically held a monopoly over the Caribbean islands and South America. The early Spanish transatlantic voyages paved the way for further European exploration of the American continent. It was in the early 17th century that other European powers in search of wealth, such as England and France, established settlements in the Caribbean. England had shown interest in the region in the preceding century.

- In 1562, the English admiral and privateer John Hawkins attacked Portuguese merchant ships and stole 300 enslaved people who he sold illegally in the Spanish Caribbean. At the time, indentured servants were being replaced by enslaved Africans. Many privateers made their fortunes through smuggling. Hawkins made two other voyages to take advantage of the lucrative slave trade in the Caribbean in 1564–65 and 1567–69.

Portrait of John Hawkins - Hawkins was influential in encouraging others, including Francis Drake, to break Spain’s monopoly of trade in the Caribbean. Drake assaulted several Spanish settlements with the capture of the Spanish Silver Train at Nombre de Dios in March 1573, his most notable Caribbean exploit.

- The climate of Britain meant there were many products that could not be locally produced, including sugar and tobacco. The Caribbean was the perfect environment to grow these cash crops.

- The Caribbean islands offered European powers without colonies in the Americas the possibilities to develop sugar cane plantations based on the Spanish model, using enslaved African labourers. Additionally, the islands could also be used as bases for trade and piracy. English settlement in the Caribbean began with St Kitts in 1623, which became a base for further colonisation of the region, including Barbados, Montserrat, Antigua and Nevis.

- In 1625, a few English colonists were sent to Barbados, with the first settlement in the island beginning in 1627. The settlement was set up as a proprietary colony. The first settlers on the island included poor English people who worked as indentured labourers. Soon, hundreds of English people sailed there to make their fortunes in agriculture.

- In the 1640s, many freed indentured labourers left for the Americas as sugar cane plantations required large plots of land and expensive equipment that they were unable to afford.

- In 1655, the English had taken an interest in Jamaica and successfully overpowered the Spanish there. A significant number of Irish people, who were mostly political prisoners of war, were brought to the island as indentured labourers and soldiers. In the early 1670s, enslaved Africans formed the majority of the population as they were transported there to provide labour to the sugar cane plantations of the English.

- In 1672, the London-based Royal Africa Company was granted a charter to provide enslaved Africans for the Caribbean. Consequently, around 100,000 Africans were forced into slavery in the region between 1672 and 1689. The Company lost control of the transatlantic slave trade in 1689, enabling Bristol and Liverpool merchants to start participating in the trade.

- Between the 17th and 18th centuries, British colonisation in the Caribbean became linked to sugar cane plantations using slave labour imported from West Africa. Thousands of jobs were created in Britain by importing raw materials and exporting manufactured goods to supply to slave traders and the colonies. The wider British economy also improved, including financial, commercial, legal and insurance businesses related to the slave trade. While the slave trade brought huge profits and wealth for both Britain and the Caribbean, it had enduring and damaging effects on the Caribbean economies and, more importantly, on the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean islands.

Early English settlement of the Bahamas

- The Bahamas, an archipelago within the Caribbean in the Atlantic Ocean, was first claimed for Spain in the late 15th century. This claim was not strongly asserted as the Spanish had little interest in the islands except as a source of slave labour. In fact, the majority of the territory’s Indigenous population were transported to other islands as labourers over the years. With no gold to be found and the islands depopulated, the Bahamas was abandoned by Spain, but it is believed that there may have been other attempts at European colonisation during this period.

- As early as 1629, England took an interest in the Bahamas with King Charles I granting Robert Heath, attorney general of England, territories in America including “Bahama and all other Isles and Islands lying southerly there or neare upon the foresayd continent.”

- Settlement, however, was not pursued until the 1640s, when religious discord among English colonists in Bermuda spanned over to the Bahamas.

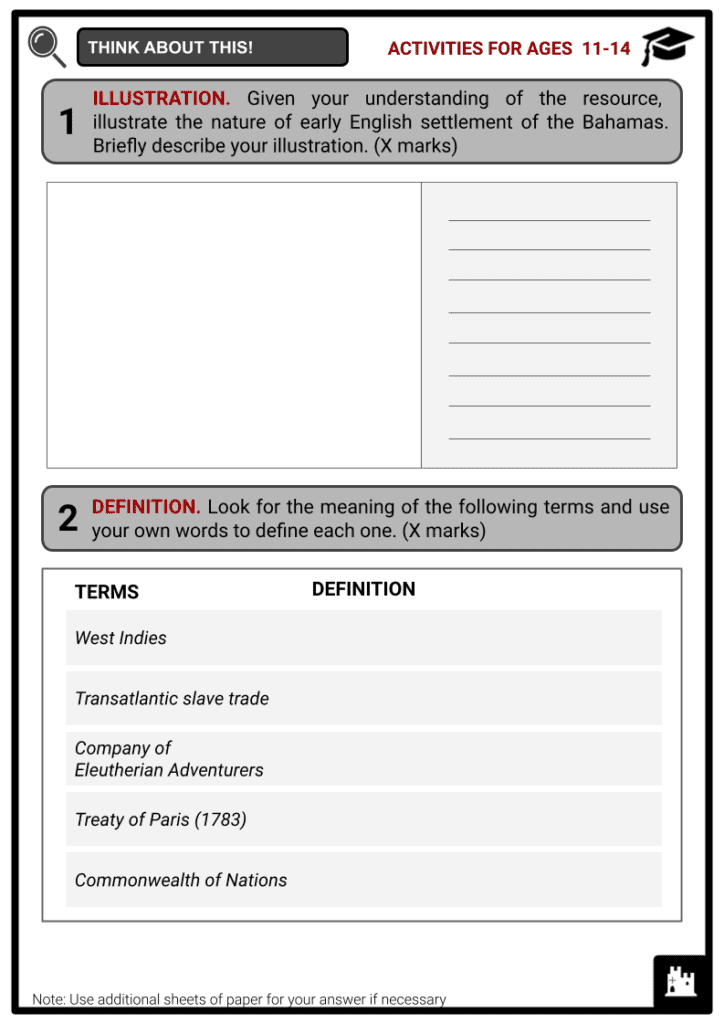

- In 1647, the Company of Eleutherian Adventurers was created in London “for the Plantation of the Islands of Eleutheria, formerly called Buhama in America, and the Adjacent Islands.”

- This was led by William Sayle and joined by around 70 prospective settlers, comprising English Puritans from Bermuda and England, with the hope of establishing a plantation colony where they could exercise greater religious freedom.

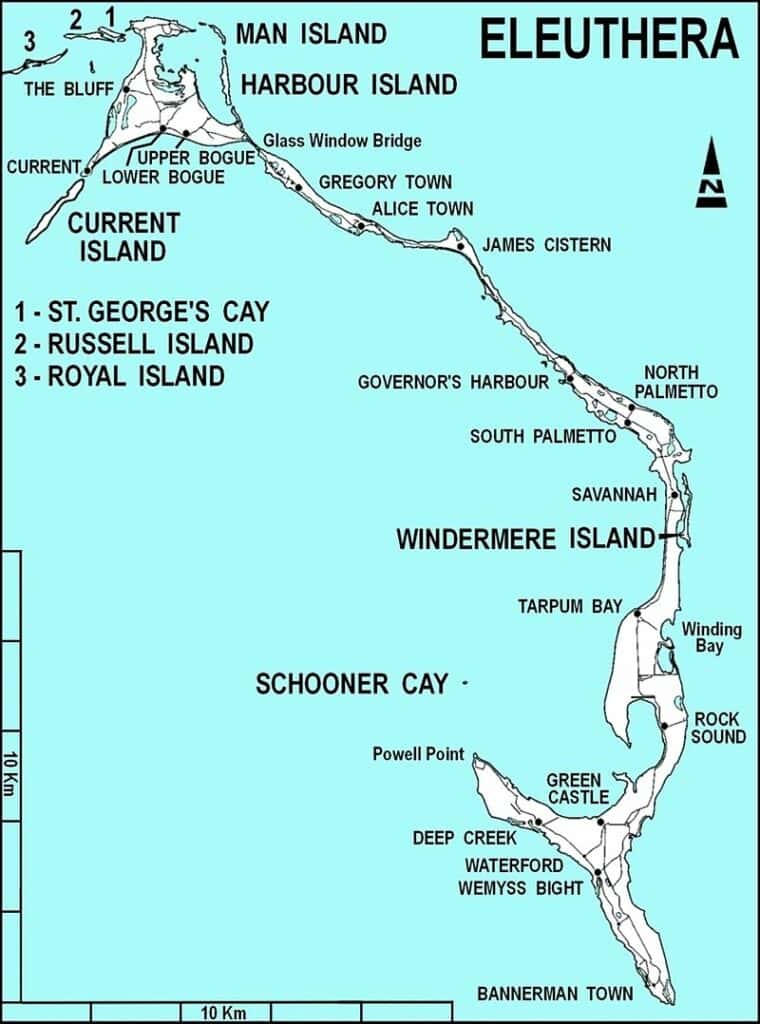

- In 1648, they arrived in Eleuthera, previously known as Cigatoo, but infertile soil, internal conflict and Spanish intrusion meant that settlement was harder than they envisioned. This led many, including Sayle, to return to Bermuda.

- Meanwhile, those who remained founded communities and had to salvage goods from wrecks to survive.

- In 1666, other English colonists from Bermuda moved to New Providence, another island in the Bahamas.

- By 1670, the English settlement in New Providence had significantly expanded. The first settlers lived off the sea, and soon, farmers from Bermuda also moved to the island.

- While both the Eleutherian and New Providence colonies were occupied by the English, neither had any legal standing under English law.

Map of Eleuthera in the Bahamas, first occupied by the English in 1648 - In 1670, the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas in North America were granted a patent for the Bahamas by King Charles II. They assumed nominal responsibility for the civil government of the islands from their base in New Providence.

- The settlers built a fort in New Providence, which they named Charles Town in honour of the English king.

- The proprietors appointed the first governor of the Bahamas, made intricate directions for its administration and instituted a parliamentary system of government. However, they took a passive approach to the settlement and development of the islands.

- Relations between the governor and the settlers were not always pleasant. The settlers found piracy the most lucrative profession.

- Consequently, the territory soon became a haven for pirates and privateers because of its shallow waters and hundreds of islands, and its proximity to the trade route.

- The pillaging of Spanish ships often provoked retaliatory attacks on the islands. Charles Town was used as a base for privateering against foreign raids.

- The governor’s support for privateering violated and undermined the 1667 and 1670 peace treaties signed between the English and Spanish.

- In 1684, the English king himself intervened and commanded that a law be passed against the pirates, but this was not effective.

- In the same year, a Spanish expedition raided Charlestown, reducing the English settlements and defences to ruins. The colonists sought refuge in other Caribbean territories, abandoning the Bahamas.

- The Bahamas was depopulated for a couple of years until 1686, when the English colonists from Jamaica settled New Providence. A new governor was also appointed and sailed from England. In 1695, the Bahamas was rebuilt under new administration, and Charles Town was renamed Nassau in honour of King William III, who belonged to the House of Orange-Nassau.

Development in the Bahamas colony

- The 1690s saw the Bahamas becoming a base of English privateers. At the time, England was at war with France. When the war concluded in 1697, many privateers turned to piracy, and Nassau became the base of pirates. Most governors appointed by the proprietors were suspected of dealing with pirates.

- England was at war with France and Spain by 1701. Combined French–Spanish fleets assailed and plundered Nassau in the succeeding years, which made some settlers leave the territory.

- By 1717, the proprietors were prepared to surrender the civil and military government to the king while retaining the title of the colony after they were persuaded by Woodes Rogers and others. King George I then made the Bahamas a British Crown colony and commissioned Rogers as its first royal governor. Rogers was tasked to eradicate piracy and restore order in the colony.

A depiction of the pirate captain Henry Every who was believed to have bribed the governor of the Bahamas When he arrived in 1718 with his troops, many pirates surrendered and received the king’s pardon. Those who resisted either fled or were hanged. Although Rogers faced difficulty, his measures proved to be effective. With the suppression of piracy, the colony was able to adopt the motto ‘Expulsis piratis restituta commercia’, which meant ‘Pirates repulsed, commerce restored’.

- In 1718, Britain and Spain were at war again, known as the War of the Quadruple Alliance. This led the British government to commission many of the former pirates as privateers. The defences of Nassau were continuously improved, with Rogers forced to use his personal fortune. It was in 1720 that the Spanish attacked Nassau.

- Rogers was replaced as governor of the colony and was again appointed for a second term in 1728. After the settlers demanded an assembly, Rogers issued a proclamation summoning a representative assembly in 1729. The British settlers were granted some degree of self-governance, and order was restituted in the government.

- The Bahamas was plagued with attacks by American and allied forces during the American War of Independence. In 1776, American forces assaulted and then briefly occupied Nassau. In 1782, Spanish troops successfully captured the Bahamas. In 1783, a British–American Loyalist expedition reclaimed the colony. Spain ceded the Bahamas to Britain in accordance with the Treaty of Paris (1783).

- When the American Revolution ended, numerous loyalists emigrated from the United States to the Bahamas and were issued land grants by Britain. They brought their enslaved people with them, remarkably increasing the colony’s population. They developed cotton plantations, which worked well for a few years.

- In 1787, the proprietors gave up their remaining rights in the colony for £12,000.

- In 1807, the slave trade was abolished in the British Empire. This contributed to the decline of the cotton plantations. Britain pressured other slave-trading countries to also discontinue the practice, and granted the Royal Navy the right to take hold of ships carrying enslaved Africans.

- The Bahamas became home to thousands of Africans freed from slave ships, and remained to be the destination of many enslaved people seeking freedom over the years. Many enslaved people in the colony were also freed following the 1818 ruling of the Home Office in London that ‘any slave brought to the Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be manumitted’. This caused tensions between Britain and the US and was only resolved in 1853.

- In 1834, slavery was abolished in the British Empire, and full emancipation came in 1838. The plantation industry eventually collapsed, which affected the condition of not only the Bahamas but also the Caribbean. Both the emancipated people and former enslavers struggled in the colony. Many of the emancipated took to subsistence farming, while others continued to work on the land of their former enslavers.

- During the American Civil War (1861–65), the Bahamas briefly benefited as it was a focus for blockade runners aiding the Confederacy. When the conflict ended, so did the period of prosperity.

- In the early 20th century, the Bahamas struggled with a stagnant economy and widespread poverty. Many survived through subsistence farming and fishing.

- During the First World War, the colony joined the Allied war effort, sending hundreds of soldiers to fight in the British West Indies Regiment, raising funds, and collecting food and clothing for soldiers and civilians in Europe.

- During the Second World War, the Bahamas became the centre of flight training and anti-submarine operations for the Caribbean, with New Providence as a key training ground for aircrews.

Duke of Windsor - In 1940–45, the Duke of Windsor, who previously abdicated the throne, served as governor of the Bahamas. He appeared disdainful of the people of the Bahamas and referred to the territory as ‘a third-class British colony’. During his term, his efforts to combat poverty and suppress civil unrest were commended.

- After the Second World War II, there were initiatives to establish tourism as the basis of the economy. The establishment of the free trade area in the town of Freeport in 1955 encouraged tourism and attracted offshore banking. This later transformed the economic and social structure of the territory.

Road to independence

- The Bahamas were given some form of self-governance since 1729. Modern political development proceeded in the 1950s with the formation of the first political parties in the colony, such as the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) in 1953, and the United Bahamian Party (UBP) in 1956.

- The white minority had governed the colony for years, hence the PLP was set up by people of African descent to contest the group in power.

- In 1956, members of the governing white minority known locally as ‘The Bay Street Boys’ realised the threat posed by the Black-dominated PLP to their political dominance and responded by forming the UBP.

- The PLP emerged as the largest party in the 1956 general election, and the young Black lawyer Lynden Pindling was one of the PLP elected to the House of Assembly.

- Pindling continued to be a prominent member of the PLP, eventually becoming leader of the party in 1961.

- In 1962, the PLP was hopeful that the election would be in its favour as women were given the vote for the first time. While it received the majority of the votes, the UBP was able to win the majority of the House of Assembly seats, largely as a result of gerrymandering.

- In 1963, a conference held in London led to the establishment of a new constitution. The new constitution that granted full internal autonomy to the Bahamas came into effect in 1964. Meanwhile, Britain retained power over foreign affairs, defence and internal security.

- These developments set the stage for the victory of the PLP under Pindling’s leadership in the 1967 elections. Pindling, as the leader of the colony started to use the title of Premier.

- The PLP pressed for tighter government control of the economy and total independence.

- In 1969, the name Commonwealth of the Bahama Islands was adopted.

- In 1972, the PLP, which actively campaigned for independence, had a decisive victory in the elections, and so negotiations with Britain over independence began. On 10 July 1973, the Bahamas became independent within the Commonwealth of Nations. Pindling was the nation’s first Prime Minister and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II thereafter.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Map_of_The_Bahamas_%281888%29.jpg/800px-Map_of_The_Bahamas_%281888%29.jpg?20140218142108

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/John_Hawkins.JPG/800px-John_Hawkins.JPG

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Eleuthera_map.jpg/800px-Eleuthera_map.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5c/Henry_Every.gif

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/The_Duke_of_Windsor_%281945%29.jpg/170px-The_Duke_of_Windsor_%281945%29.jpg

Frequently Asked Questions

- When did the British first establish control over the Bahamas?

The British established control over the Bahamas in 1718, following years of intermittent colonisation attempts.

- When did the Bahamas gain independence from British rule?

The Bahamas gained independence on 10 July 1973.

- Who owned the Bahamas before the British?

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Bahamas were inhabited by the Lucayan Taino people. The Lucayans were a subgroup of the Taino, the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. Christopher Columbus is credited as the first European to set foot in the Bahamas during his first voyage to the Americas in 1492.