Jacobite Rising of 1745 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Jacobite Rising of 1745 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Political Background

- Preparing for the Rebellion

- England Invasion

- Battle of Culloden

- The Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Jacobite Rising of 1745!

The Forty-five Rebellion, alternatively named the Jacobite Rising of 1745, was an endeavour by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British crown on behalf of his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. This event transpired amid the War of the Austrian Succession, a period when a significant portion of the British Army was engaged in conflicts on the European continent. It marked the culmination of a series of revolts that commenced in March 1689, with notable uprisings occurring in 1708, 1715 and 1719.

Political Background

- In 1688, a significant event known as the 'Glorious Revolution' took place. Parliament and a predominantly Protestant political community removed King James II, a Roman Catholic, due to his arbitrary actions and efforts to build a strong standing army, which seemed to suggest the establishment of an absolute Catholic monarchy.

- The phrase 'Glorious Revolution' denotes the sequence of occurrences in 1688–1689 that led to the expulsion of King James II and the ascension of William and Mary to the throne. Furthermore, many perceive the Glorious Revolution as a pivotal moment in the evolution of the constitution, specifically in shaping the role of Parliament.

- After James II, his Protestant daughters, Mary and Anne, became rulers. However, when Anne passed away in 1714 without a successor, Parliament chose to replace the Stuart dynasty with their German relatives, the Hanoverians. The claims of James II's Catholic son, known as the 'Old Pretender' and named James Francis Edward, were disregarded.

- King James II served as the final Catholic ruler of England, Scotland and Ireland. With support from either France or Spain, he tried to incite rebellion in Scotland in 1708, 1715 and 1719.

- However, by 1745, despite ongoing unpopularity, the Hanoverian dynasty seemed firmly established.

- Prince Charles Edward Stuart, commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie and referred to as 'The Young Pretender', was born in Rome in 1720. The Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 marked Charles's endeavour to reinstate his father to the British throne.

- Jacobitism, a political movement, advocated reinstating the senior Stuart dynasty on the British throne. The name is derived from the first name of James II of England, which is spelt Jacobus in Latin.

- By this point, Mary had passed away in 1694, William in 1702, Queen Anne (also The Old Pretender's half-sister) in 1714, and with none of her 18 children surviving infancy, the British monarchy transitioned from the Stuarts to George I of Hanover, hailing from present-day Germany. George I was Anne's closest living Protestant relative.

- Those who remained loyal to the exiled James II, referred to as Jacobus in Latin, came to be known as 'Jacobites'.

- Support for the Jacobite cause stemmed from various factors, not primarily from the belief in the legitimacy of Charles's father as the monarch. Some of Charles's counsellors were Irish exiles seeking an independent Catholic Ireland and the restoration of lands seized by the British. The broader Roman Catholic community backed the cause due to religious motivations.

- Jacobite sympathisers were often Tory political supporters who disapproved of their Whig opponents gaining political dominance around the turn of the 18th century. The Whigs favoured the Hanoverian constitutional monarchy over the Stuarts' divine right to absolute monarchy. The Whig/Hanoverian establishment was portrayed as corrupt in Jacobite propaganda.

- While English Jacobitism drew individuals who despised the political system, Scottish Jacobitism was seen as a viable alternative to the current government. Nonetheless, not all of Scotland's main clans were Jacobites.

- Another factor in Jacobitism's popularity in Scotland was opposition to the 1707 Act of Union. Supporters anticipated that a monarch from the Stuart lineage would dismantle the United Kingdom and reinstate Scotland's independence.

Preparing for the Rebellion

- During the 1740s, the British Army actively engaged in the New World during the War of Jenkins' Ear and in Europe, aligning with the Habsburg monarchy against the French, Prussians and Spanish in the War of Austrian Succession. King Philip V of Spain and King Louis XV of France collaborated to take measures against Britain, including the restoration of the Stuarts to the British throne. Louis XV informed the Old Pretender that plans for a British invasion were underway for February 1744. While James, the Old Pretender, remained in Rome, Bonnie Prince Charlie covertly joined the invasion force. Unfortunately, the invasion proved unsuccessful, leading to a deterioration in relations between Britain and France.

- In August, Charles journeyed to Paris to advocate for an alternative landing in Scotland. During his visit, he encountered Sir John Murray of Broughton, who served as the intermediary between the Stuarts and their Scottish supporters. Upon Murray's return to Scotland, the Scots conveyed their opposition to a rebellion unless substantial French support was secured. Despite this setback, Charles persisted in garnering backing for his cause on the Continent. He dedicated the early months of 1745 to procuring weapons, and on 30 April, the British and their allies experienced a significant military defeat at Fontenoy in the Austrian Netherlands.

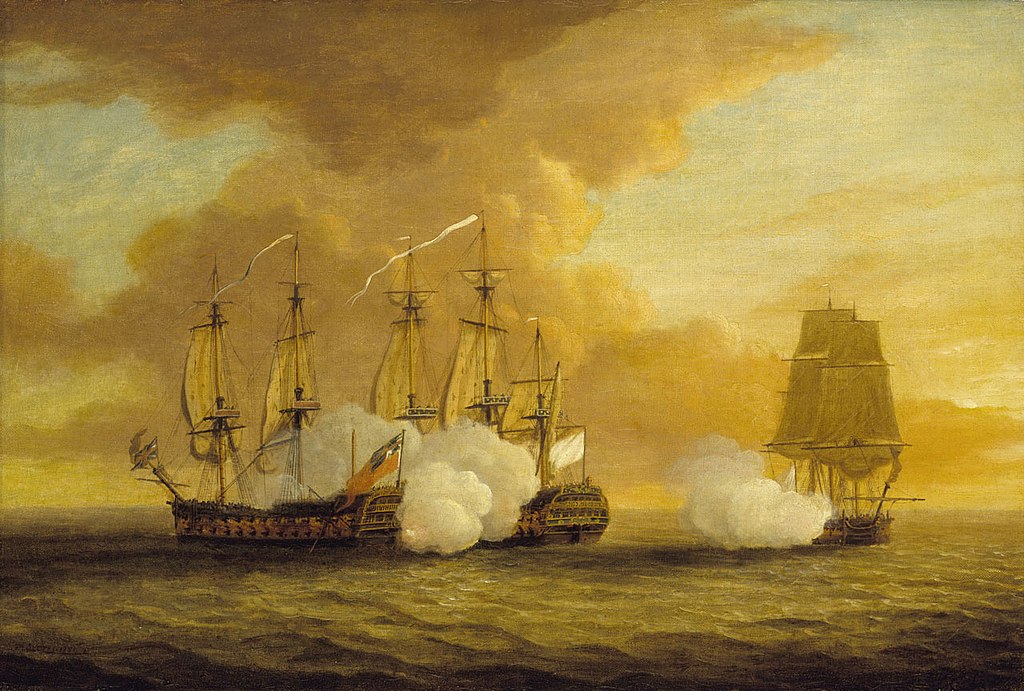

- Following their triumph, the French provided Bonnie Prince Charlie with two transport vessels: the Elisabeth, an old gun warship seized from the British in 1704, and the Du Teillay, a French 16-gun privateer.

- In July, both ships embarked on a journey to the Scottish Western Isles. However, they encountered a British ship, HMS Lion, leading to a four-hour battle that compelled both of Charles's vessels to retreat to port. While the damage to the warship posed a significant setback, the Du Teillay, which carried Charles, managed to land in the Outer Hebrides Islands of Scotland on 23 July.

- Upon Charles's arrival at Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides, several individuals he encountered advised him to return to France if there was no accompanying French military support. Some perceived him as not keeping his word and were unimpressed with his character.

- Undeterred, Charles remained resolute in his determination to reach the Scottish mainland, even in the presence of a British warship near the Eriskay harbour. He successfully landed near Moidart in the Highlands of Scotland around noon on 25 July.

- Approximately 700 troops from the Highland Army witnessed the raising of the Stuart Royal Standard (war flag) at Glenfinnan, Scotland, less than four weeks after the successful landing near Moidart on 19 August, and less than 20 miles away. This marked the commencement of the Jacobite Rebellion.

- Charles garnered some supporters, and his ranks swelled as he advanced towards Edinburgh on 17 September. His entry into the city was unopposed, and while Edinburgh Castle remained under government control, James VIII was proclaimed King of Scotland the next day. His son, Bonnie Prince Charlie, assumed the title of Regent.

- On 21 September, a Jacobite army of 2,500 faced British forces in the Battle of Prestonpans. The conflict lasted less than half an hour, with the Jacobites emerging victorious. The Duke of Cumberland, commanding the British Army in Flanders, was summoned back to London, along with 12,000 troops under his leadership.

- In October, Charles issued two declarations: one to dissolve the 'pretended Union' and another to reject the Act of Settlement, which guaranteed Protestant succession to the British throne.

- Midway through October, the Marquis d'Éguilles, an emissary from France, arrived in Scotland with weapons and money, which greatly raised morale. Although some Scots were becoming apprehensive of Charles's authoritarian ways, this appeared to indicate that Bonnie Prince Charlie had the support of the French. The Scots forced Charles to serve on a 'Prince's Council' out of concern over the influence of his Irish advisers. Charles was not amused by this imposition, and more arguments broke out when the Scots sought to gather in anticipation of the English army that they believed was imminent.

- Backed by Irish exiles, Charles asserted that launching an invasion of England was imperative to garner increased French support. Charles claimed that he had communication with English supporters eagerly anticipating his arrival, and d'Éguilles assured the Scots that the French were going to land in England soon. Despite reservations, the Council reluctantly agreed to the invasion, conditional upon the assurance that French support was on the way.

England Invasion

- By 8 November, the Jacobite forces, numbering around 5,000, crossed into England. The forces of the government commander in Newcastle, General Wade, were held up by snow for a week, which allowed them to capture a garrison at Carlisle Castle one week later. On 26 November, the Jacobites advanced to Preston, and on 28 November, they reached Manchester. The Manchester Regiment was formed by approximately 200 English soldiers who joined the Jacobite army.

- At this point, many Scots believed they had ventured far enough into England, but Charles reassured them that reinforcements would meet them in Derby, and a Tory ally was set to capture the port of Bristol. However, upon reaching Derby on 4 December, the Jacobite army found no reinforcements. The Council convened the next day to determine the next course of action.

- Despite large crowds turning out to see them on their journey south, the Jacobite stronghold of Preston only gained three new recruits. Lord George Murray, leading the Jacobite army, argued against advancing further south due to the risk of supply line cutoffs. Charles then conceded that he hadn't heard from the English Jacobites since leaving France. Caught in a significant deception, Charles's relationship with the Scots suffered irreparable damage.

- The Council opted for a retreat, especially upon receiving news that the French had delivered supplies, pay and troops back in Scotland. They were told that ten thousand French forces were en route to Scotland as well. The absence of heavy weapons allowed the Jacobite army to move swiftly, and they reached the Scottish border on 20 December, facing only a minor skirmish at Clifton Moor.

- Just two days later, the army led by the Duke of Cumberland arrived outside Carlisle, located just south of the Scottish border. The fall of the Carlisle garrison on 29 December marked the conclusion of the Jacobite presence in England.

- Despite the retreat to Scotland, the morale within the Jacobite army remained high. Reinforcements from Scotland joined their ranks, including Scottish and Irish soldiers who had previously fought for the French. The Jacobite forces swelled to a strength of 8,000 men.

- They subsequently opted to lay siege to Stirling and Stirling Castle. While the town surrendered swiftly, the castle's formidable artillery proved too challenging for the Jacobite forces to capture.

- In an attempt to relieve the siege, government forces engaged in the Battle of Falkirk Muir in January 1746, from which Charles emerged victorious. However, unable to seize the castle, they had to abandon the siege and redirect northwards to Crieff and later Inverness.

- They sought refuge in Inverness until the weather improved, but were eventually pursued by the forces led by Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, who was the son of George II.

- As Cumberland departed Aberdeen on 8 April, the Jacobites found themselves facing shortages of both food and funds. Despite these challenges, the leadership concurred that engaging in battle was their most viable option. They placed their reliance on the Highland charge, characterised by speed and ferocity to break through enemy lines.

- However, the Duke of Cumberland's forces not only outnumbered and out-equipped the Jacobites but were also well-trained in countering the Highland charge. The two forces would have their decisive encounter at Culloden in the Scottish Highlands near Inverness.

Battle of Culloden

- On 16 April 1746, the final battle of the Jacobite Rebellion began with an exchange of artillery. Charles held his position, anticipating an onslaught from Cumberland, despite the loss of their injured artillery commander from Fort William. Cumberland, on the other hand, refrained from advancing, leaving the Jacobite forces unable to counterattack.

- As a result, Charles ordered his soldiers to charge, abandoning their muskets in favour of swords in preparation for hand-to-hand battle. The muddy ground ahead of their centre shattered their formation, increasing the distance they had to traverse. With their momentum hampered by government artillery, the Jacobite forces proved inferior to the government troops. The Highlanders broke ranks and fled in chaos. Recognising that the battle had been lost, Charles and his party withdrew to the north.

- Overall, the Battle of Culloden lasted less than half an hour. The Jacobites lost between 1,200 and 1,500 soldiers, with another 500 captured. Cumberland lost only 50 men, with another 250 injured. The Jacobites had not given up hope, and 5,000 or 6,000 men stayed armed at the location for the following two days. Charles issued his final order to the remaining troops from afar on 20 April, instructing them to seek safety.

- He then spent five months evading British authorities in the Western Highlands, living in caves at times. A French ship picked him up and sent him to France in September 1746 and he never returned to Scotland.

The Aftermath

- The British government imposed harsh retaliation on individuals who had participated in the Jacobite Rebellion. Approximately 3,500 captured Jacobites were charged with treason, and approximately 120 were executed. Another 650 died in custody while awaiting trial, 900 were pardoned, and the remainder were sent to British territories in the Americas.

- The government refrained from confiscating additional Jacobite estates because the expenses involved were often higher than the acquisition cost. Due to challenges faced by British forces in advancing north of Edinburgh, especially in the Highlands, new forts were constructed, and the military road network was completed.

- The Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 prompted the first thorough survey of the Highlands. The British government proceeded to undermine the Scottish clan system, effectively eradicating the feudal influence of Scottish clan leaders over their members. The British government prohibited the wearing of traditional Highland garb unless it was worn while serving in the military, although this restriction was lifted in 1782.

- While Jacobite support did not completely fade after 1746, it was never a serious political threat again. d'Éguilles published a report on the Rebellion in June 1747. He criticised the Jacobite leadership in general, but he was so critical of Charles that he proposed that France back a Scottish republic from then on.

- Charles himself succumbed to drunkenness. He was deported from France in 1748, and he made a few futile attempts to revive the Jacobite cause in the following years. Pope Clement XIII declined to acknowledge him as King Charles III following his father's death in 1766. Charles passed away due to a stroke in Rome in January 1788, over 41 years after departing the territory he aspired to govern.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacobite_rising_of_1745#/media/File:Gentlemen_he_cried,_drawing_his_sword,_I_have_thrown_away_the_scabbard.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Lion_(1709)#/media/File:Action_between_HMS_Lion_and_Elizabeth_and_the_Du_Teillay,_9_July_1745_BHC0364.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Culloden#/media/File:The_Battle_of_Culloden.jpg

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the Jacobite Rising of 1745?

The Jacobite Rising of 1745, also known as the "Forty-Five Rebellion," was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to restore the exiled Stuart monarchy to the British throne.

- What were the motivations behind the Jacobite Rising?

The Jacobites sought to restore the Stuart monarchy, which had been deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. They aimed to overturn the Protestant Hanoverian succession, favouring the Catholic Stuarts.

- Who was Charles Edward Stuart?

Charles Edward Stuart, or Bonnie Prince Charlie, was the grandson of James II of England, who led the Jacobite Rising of 1745 to reclaim the Stuart dynasty's throne.